Mammals of today possess exceptional auditory capabilities, discerning a wide spectrum of sound intensities and frequencies via their middle ear structures, which include our tympanic membranes and a trio of minute ossicles.

A recent investigation conducted by paleontological researchers at the University of Chicago in the United States has demonstrated that these anatomical characteristics originated approximately 50 million years prior to previous estimations.

Their corroborating evidence was unearthed from a 250-million-year-old fossil specimen of the mammalian progenitor, Thrinaxodon liorhinus. Through the application of computed tomography imaging on the creature’s cranial and mandibular bones, they meticulously constructed three-dimensional digital representations. These models facilitated a simulation of how Thrinaxodon‘s physiology might have responded to varying sound pressures and frequencies, employing sophisticated engineering software to meticulously analyze the oscillation patterns of its skeletal components.

Thrinaxodon existed during the Early Triassic epoch, predating the emergence of the first dinosaurs. It belonged to the cynodont lineage – a group closely allied with early mammalian forms – and presented a physique resembling a hybrid of a lizard and a fox.

Certain genetic sequences within this species align with the fundamental genetic architecture found in contemporary mammals, and this novel research posits that the structural framework of its auditory system is also a shared evolutionary inheritance.

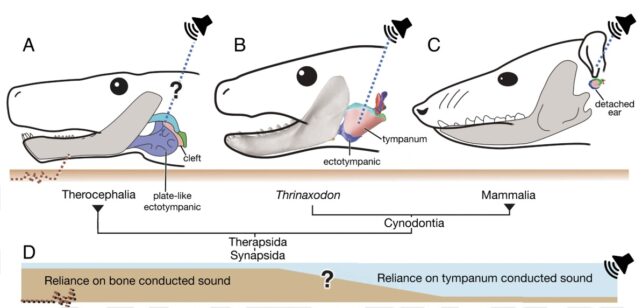

Initial cynodonts possessed auditory ossicles – specifically the malleus, incus, and stapes – which remained integrated with their mandibles. In subsequent evolutionary stages, these minuscule bony fragments gradually disengaged from the jaw, ultimately coalescing to form the distinct middle ear characteristic of mammals.

Prior to the advent of the middle ear and its associated ‘tympanic’ auditory functions, terrestrial fauna relied on sound transmission through bone conduction, wherein neural pathways conveyed vibrational signals from the jawbone to the brain.

For several decades, paleontologists have theorized that Thrinaxodon could represent a pivotal ‘missing link’ in the evolutionary trajectory of mammalian hearing. In 1975, Edgar Allin, an anatomist from the University of Wisconsin, advanced the hypothesis that Thrinaxodon might have possessed a rudimentary form of an eardrum, stretched across the still-articulated, hook-shaped bony structure projecting from its jaw.

However, at that juncture, Allin lacked the technological means to substantiate his conjecture, prompting the current research team to re-examine this question utilizing contemporary engineering methodologies.

“For nearly a century, scientific inquiry has been devoted to deciphering the auditory mechanisms of these ancient creatures. These postulates have profoundly stimulated the imagination of paleontologists specializing in mammalian evolution, yet robust biomechanical validation has remained elusive until this present moment,” states Alec Wilken, an evolutionary scientist affiliated with the University of Chicago. He further elaborated.

“We addressed a complex scientific challenge – specifically, the biomechanics of ear bone oscillation in a 250-million-year-old fossil – by rigorously testing a straightforward hypothesis through the deployment of advanced computational tools.”

The meticulously generated three-dimensional model afforded the research cadre an opportunity to scrutinize the fossilized skull and mandible with unparalleled granularity, including the specific curvature of the jawbone that would have potentially accommodated an early tympanic membrane.

Subsequently, employing a software suite typically utilized by engineers for assessing vibrational stresses on critical infrastructure such as aircraft and bridges, they simulated the impact of a spectrum of auditory stimuli on Thrinaxodon‘s cranial and mandibular structures.

It is acknowledged that a living organism’s auditory apparatus comprises more than just osseous tissue; consequently, the researchers incorporated known parameters from extant fauna to reconstruct the potential role of associated soft tissues.

“Once we obtain the CT model derived from the fossil, we can integrate material characteristics from extant species, effectively animating our Thrinaxodon specimen,” observes Zhe-Xi Luo, Wilken’s academic mentor. “This capability, previously unattainable, allowed our software simulation to conclusively demonstrate that auditory perception was primarily mediated through vibratory sound transmission for this organism.” He remarked.

Collectively, the findings indicate that Thrinaxodon‘s tympanic membrane would have functioned effectively even without the presence of detached middle-ear ossicles. This represented a significant advancement over bone conduction, potentially signifying a transitional phase in the evolution of mammalian reliance on tympanic hearing.

Wilken and his colleagues conservatively estimate that, equipped with this inherent auditory apparatus, Thrinaxodon could perceive sounds ranging from 38 to 1,243 hertz (for comparative context, a healthy juvenile can detect frequencies approximately from 20 to 20,000 hertz). The species exhibited maximal sensitivity to sonic frequencies around 1,000 hertz at a sound pressure level of 28 decibels, a volume akin to the transition between a whisper and normal conversation.

This refined auditory acuity would have conferred substantial advantages upon Thrinaxodon, aiding in the detection of prey, evasion of predators, and potentially playing a role in reproductive behaviors.