Could humankind employ a nuclear detonation against an impending asteroid to alter its course and safeguard the planet, much like in cinematic disaster narratives? A novel simulation focused on impact dynamics suggests that a nuclear strategy could indeed serve as a feasible final recourse to avert a global catastrophe.

Recent investigations have revealed that celestial bodies of this nature can endure significantly greater forces than prior experimental and observational data had indicated. In a seemingly paradoxical manner, these asteroids actually exhibit increased resilience when subjected to forceful impacts.

While this revelation might appear disheartening, such findings have the potential to enhance strategies for planetary defense. This is because it implies that a nuclear-affected asteroid would likely remain intact, rather than fracturing into numerous fragments that could subsequently bombard our planet.

As elucidated in a recently disseminated publication, a collaborative group of scientists, which included physicists from the University of Oxford and representatives from the Outer Solar System Company (OuSoCo), a nascent enterprise specializing in nuclear deflection technologies, undertook an analysis of an iron-rich space rock’s behavior under varying stress conditions.

“These analytical endeavors are designed to scrutinize alterations within the meteorite’s internal composition stemming from radiation exposure and to validate, at a microscopic level, the enhancement in material tenacity by a factor of 2.5, as suggested by the experimental outcomes,” states Melanie Bochmann, a co-founder of OuSoCo and a principal investigator for the research initiative.

Analogous to the DART mission showcased in 2022, a compelling method to circumvent an asteroid-precipitated global disaster involves diverting the approaching celestial threat using a kinetic impactor. This involves deploying a human-engineered cosmic projectile designed to collide with a menacing asteroid at velocities far exceeding those of a bullet.

The concept is straightforward, yet its practical execution is fraught with considerable peril and uncertainty. An ill-placed impact might merely postpone the asteroid’s calamitous trajectory towards Earth. Furthermore, the kinetic energy imparted by the impactor, coupled with the asteroid’s material response, could precipitate unforeseen outcomes such as fragmentation or an unexpected alteration in its momentum.

Consequently, to make an informed decision between employing an impactor like DART or an as-yet unproven nuclear approach, planetary defense experts must accurately determine the mechanical characteristics of diverse asteroid materials. This critical knowledge is indispensable for effectively transferring energy to the celestial body and reorienting its path away from our planet.

However, such empirical data remains exceedingly limited, particularly concerning the real-time reactions of materials. For instance, various predictive models offer divergent estimations for yield strength, a metric quantifying the ease with which a body fractures under duress.

These models can exhibit discrepancies of up to a seven-fold difference, contingent upon whether they assess local (microscopic) or bulk (macroscopic) properties. Moreover, the inherently destructive nature of prior testing methodologies has hindered the direct observation and measurement of material responses as they transpire.

“This represents the inaugural instance where we’ve been able to non-destructively and in real-time observe the deformation, hardening, and adaptive behavior of an actual meteorite sample under extreme conditions,” observes Gianluca Gregori, a physicist affiliated with the University of Oxford and a co-author of the study.

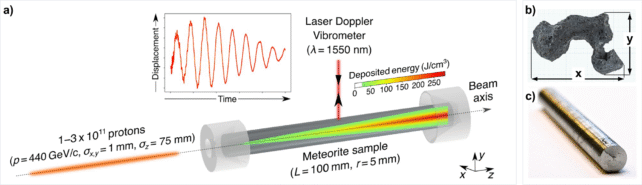

The research team utilized an innovative methodology to ensure the integrity of their observations. They leveraged the Super Proton Synchrotron particle accelerator at CERN’s High Radiation to Materials (HiRadMat) facility. Here, they subjected a sample derived from a Campo del Cielo iron meteorite to irradiation by high-energy, short-duration proton beam pulses at varying intensity levels.

The resultant data, gathered through temperature sensors and laser Doppler vibrometry (a technique used to analyze vibrational patterns on surfaces), indicated that the meteorite sample initially softened and flexed before undergoing a surprising re-strengthening process. It also exhibited a phenomenon known as strain-rate dependent damping, signifying that the greater the impact force, the more effectively it dissipates energy.

This experimental approach yields crucial insights that elucidate the reasons for disparities in yield strength observed in prior laboratory experiments when contrasted with evidence of meteorite fragmentation within Earth’s atmosphere. These discrepancies, the study suggests, are attributable to factors such as the internal redistribution of stresses.

Furthermore, it underscores the dynamic nature of these mechanical properties, which evolve in real time and should not be presumed to be static, as is often the assumption in current asteroid deflection models. Subsequent investigations will encompass a broader spectrum of asteroid compositions.

The researchers selected an iron-rich sample for this particular study due to its relatively uniform composition. However, more variegated celestial bodies are anticipated to demonstrate differing capacities for stress dissipation, influenced by the spatial arrangement of their constituent materials.

Ideally, the ultimate application of this research will remain within the theoretical realm:

“The global community requires the capability to execute a highly reliable nuclear deflection mission, yet real-world testing for such a scenario is unfeasible. This imposes exceptionally stringent demands on the quality of material and physics data,” concludes Karl-Georg Schlesinger, a co-founder of OuSoCo and a leading researcher on the team.

Nevertheless, should a nuclear intervention become an absolute necessity, it would likely diverge significantly from cinematic depictions – no physical penetration would be required. Rather than embedding explosives within an asteroid, some physicists propose detonating a nuclear device at a distance near the celestial body. This standoff detonation would serve to vaporize a portion of its mass, thereby altering its orbital trajectory.

This groundbreaking research has been published in the esteemed journal Nature Communications.