Remarkable findings concerning parasites have emerged from an unlikely repository: the forgotten corners of a natural history collection. Canned salmon, long past its consumption date, has effectively preserved a multi-decade record of Alaskan marine ecosystems within its saline and metallic confines.

Parasites serve as invaluable indicators of ecological health, given their intricate relationships with numerous host species. However, their significance has largely been overlooked unless they pose a direct threat to human well-being.

This historical neglect presents a challenge for parasitic ecologists, such as Natalie Mastick and Chelsea Wood of the University of Washington. They had been actively seeking a method to retrospectively assess the impact of parasites on marine mammals inhabiting the Pacific Northwest.

Consequently, when Wood received an inquiry from the Seattle Seafood Products Association regarding their willingness to assume custody of numerous dusty, expired salmon cans—some dating back to the 1970s—her response was an emphatic affirmative.

These cans, maintained for decades as part of the association’s quality assurance protocols, were transformed in the hands of these ecologists into an exceptionally preserved archive. This archive did not document salmon morphology but rather yielded a wealth of preserved parasitic specimens.

A synthesized overview of this research is available in the following video:

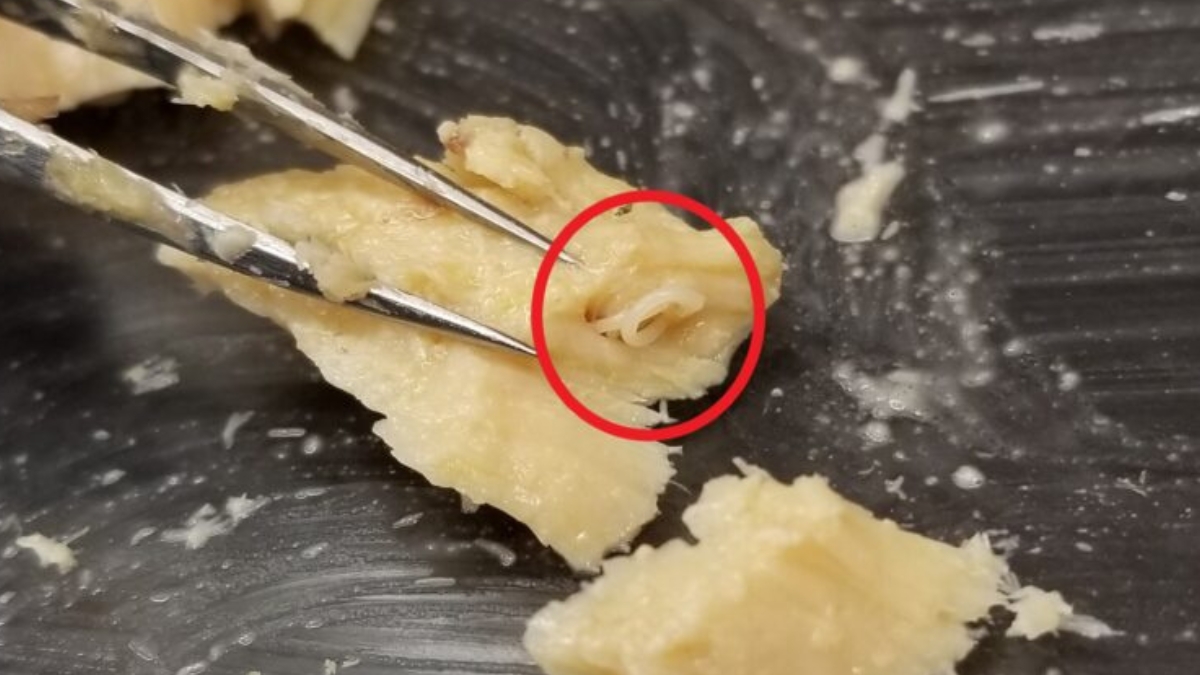

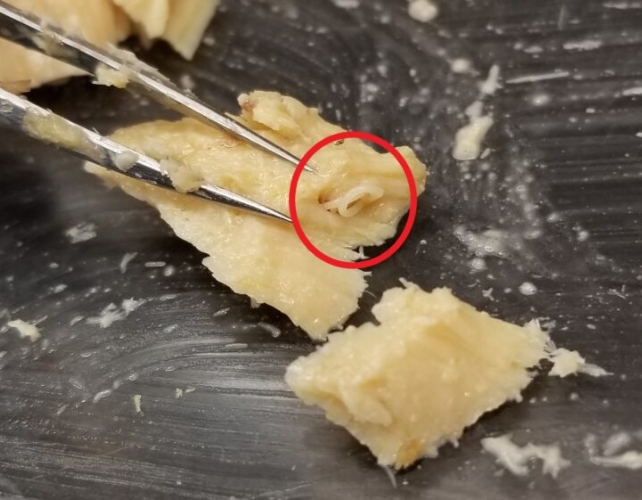

While the notion of encountering nematodes within preserved fish may elicit unease, these marine parasites, known as anisakids and measuring approximately 1 centimeter in length, pose no risk to human health when neutralized by the canning process.

“The prevailing assumption is that the presence of nematodes in salmon signifies a compromise in quality,” stated Wood, as reported upon the research’s publication in 2024.

“However, the anisakid life cycle encompasses multiple trophic levels. I interpret their presence as an indicator of a robust ecosystem from which the fish on your plate originated.”

Anisakids infiltrate the food web when consumed by organisms like krill, which are subsequently preyed upon by larger marine fauna.

This sequence of consumption leads to the presence of anisakids in salmon and, ultimately, within the digestive tracts of marine mammals, where they complete their reproductive cycle. Their ova are then disseminated into the oceanic environment by these mammals, reinitiating the parasitic life cycle.

“In the absence of a suitable host, such as marine mammals, anisakids are unable to conclude their life cycle, resulting in a decline in their population numbers,” Wood, the senior author of the study, explained.

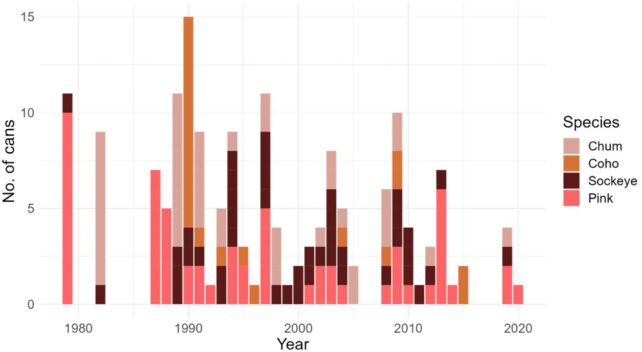

The collection of 178 metal cans, constituting the ‘archive,’ contained specimens from four distinct salmon species harvested from the Gulf of Alaska and Bristol Bay over a span of 42 years (1979–2021). This included 42 cans of chum (Oncorhynchus keta), 22 of coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch), 62 of pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), and 52 of sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka).

Although the preservation techniques employed for the salmon do not, fortunately, maintain the worms in an ideal state, the researchers successfully dissected the fillets to quantify the parasite load per gram of fish.

Their analysis revealed an increase in worm prevalence over time in chum and pink salmon, whereas sockeye and coho salmon exhibited stable parasite levels.

“Observing an upward trend in their population counts, as we did with pink and chum salmon, suggests that these parasites encountered the necessary hosts and successfully reproduced,” stated Mastick, the study’s lead author.

“This finding could signify a stable or rebounding ecosystem, characterized by a sufficient presence of the specific hosts required by anisakids.”

However, the consistent parasite levels observed in coho and sockeye salmon present a more complex scenario, particularly given the challenges in definitively identifying the specific anisakid species due to the canning process.

“While our identification to the family level is reliable, we were unable to ascertain the precise species of the detected [anisakids],” the authors noted in their publication.

“Consequently, it is plausible that subspecies of anisakids associated with a proliferating species preferentially infect pink and chum salmon, whereas those linked to a stable population may target coho and sockeye.”

Mastick and her collaborators hypothesize that this innovative investigative methodology—utilizing antiquated canned goods as a proxy for ecological data—holds the potential to catalyze numerous future scientific breakthroughs. It appears they have indeed unearthed a significant scientific quandary.

This research has been published in the journal Ecology and Evolution.