A simultaneous global illumination event would precipitate a significant surge in the demand for electrical energy, the resource most individuals across the planet rely upon to power their lighting systems.

Electrical power is a manifestation of energy, the generation of which is achieved through a diverse array of fuel sources. Power generation facilities, essentially energy conversion plants, produce electricity by harnessing resources such as coal, natural gas, nuclear material, flowing water, wind currents, and solar radiation. This generated electricity is then channeled into an intricate network of high-voltage transmission lines and lower-voltage distribution conduits, collectively known as the power grid, which subsequently delivers the energy to residential dwellings and commercial establishments.

The integrity and stability of the power grid are contingent upon a precise equilibrium between electricity supply and emergent demand. The activation of a light fixture results in the withdrawal of power from the grid. Consequently, generating units must instantaneously compensate by injecting an equivalent quantum of power back into the grid. Any disruption to this delicate balance, even for a fleeting duration, carries the potential to instigate widespread power outages.

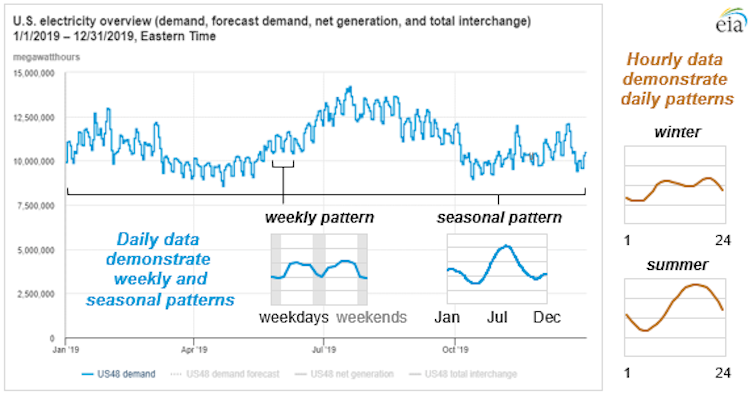

Grid operators meticulously monitor electricity consumption using an array of sensors and advanced computational systems. This continuous oversight enables them to modulate power output, increasing or decreasing it in response to fluctuations in demand. The aggregate power requirement, termed ‘load,’ exhibits considerable variability, fluctuating significantly on an hourly and seasonal basis.

To grasp this phenomenon, consider the disparity in electrical energy consumption within a household between daylight hours and the deep of night, or contrast the energy needs during a sweltering summer heatwave with those of a mild autumn day.

Addressing a Demand Escalation

Were every individual across the globe to simultaneously activate their lighting systems, an immense and sudden surge in electrical demand would be generated. Power generation facilities would face the imperative to rapidly augment their output to preclude a catastrophic system failure. However, the capacity of these facilities to adapt to shifting demand varies considerably.

Nuclear and coal-fired power plants possess the ability to deliver substantial quantities of electricity at virtually any moment. Nevertheless, if these plants are taken offline for maintenance or experience operational malfunctions, their recommissioning can necessitate many hours. Furthermore, their response to load adjustments is characteristically sluggish.

Power plants fueled by natural gas exhibit a more agile response to evolving load demands, making them the preferred option for meeting peak electricity requirements, such as those experienced during hot, sun-drenched summer afternoons.

Renewable energy sources, including solar, wind, and hydroelectric power, contribute to reduced pollution levels but are inherently less controllable. This variability stems from the inconsistent nature of wind speeds and the fluctuating intensity of sunlight experienced in most geographical locations.

Ancillary energy storage systems, notably large-scale battery banks, are strategically employed by grid managers to mitigate fluctuations in power flow as demand fluctuates. However, the current capacity of battery storage is insufficient to sustain the energy needs of an entire municipality or city.

Certain hydroelectric facilities are equipped with the capability to pump water into reservoirs during periods of low energy demand. This stored water can subsequently be released to drive turbines and generate electricity when demand escalates.

Fortuitously, if a universal simultaneous activation of lights were to occur, two key factors would contribute to averting a complete grid collapse. Firstly, a singular, interconnected global power grid does not exist. The majority of nations operate their own independent grids, or a series of interconnected regional networks.

Adjacent power grids, such as those linking the United States and Canada, are typically interconnected to facilitate cross-border electricity transfers. Nevertheless, these connections possess the capacity for rapid disengagement, thereby mitigating the likelihood of a cascading failure affecting all grids concurrently, even in the event of localized power disruptions.

Secondly, over the past two decades, a significant transition has taken place, with light-emitting diodes (LEDs) supplanting many conventional incandescent and fluorescent lighting technologies. LEDs operate on fundamentally different principles compared to older bulb designs, producing substantially more illumination per unit of electrical energy consumed, thus reducing the power drawn from the grid.

According to data from the U.S. Department of Energy, the adoption of LED bulbs results in annual savings of approximately $225 for the average household. As of 2020, a substantial proportion of American residences had integrated LEDs for the majority, if not all, of their lighting requirements.

Amplified Glare, Diminished Starlight

Beyond the immediate impact on power consumption, it is imperative to consider the broader implications of such an extensive illumination event. A precipitous increase in lighting would lead to a dramatic exacerbation of sky glow—the pervasive luminescence that envelops urban and suburban areas during nighttime hours.

Sky glow arises from the atmospheric scattering of light by airborne particulates and haze, creating a diffuse radiance that obscures celestial visibility. The directionality of light is notoriously difficult to contain; for instance, it can readily reflect off highly reflective surfaces such as vehicular windshields and concrete structures.

Artificial lighting is regrettably overutilized during nighttime periods. Examples abound, including office buildings illuminated continuously, and streetlights that cast their beams skyward rather than illuminating the roadways and pedestrian pathways where light is genuinely needed.

NPS/Lian Law

Even meticulously designed lighting installations can contribute to this pervasive issue, rendering metropolitan areas and thoroughfares discernible from orbital vantage points, while rendering celestial observation from ground level impossible. This detrimental phenomenon, known as light pollution, can adversely affect human health by disrupting the body’s natural circadian rhythms, which govern sleep and wakefulness cycles. Furthermore, it poses a significant threat to various fauna, disorienting insects, avian species, marine turtles, and numerous other forms of wildlife.

In summation, a simultaneous global illumination event would precipitate a modest increase in energy consumption, accompanied by a substantial augmentation of sky glow, effectively obliterating the constellations from view. Such a scenario offers a decidedly unappealing nocturnal vista.