While the intricate mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease remain largely enigmatic, the correlation between suboptimal sleep patterns and the exacerbation of this neurodegenerative condition is an area of fervent scientific investigation.

A notable 2023 publication revealed that pharmacological interventions to enhance sleep could potentially mitigate the accumulation of deleterious protein aggregates within the brain’s nightly cleansing fluid.

Participants administered suvorexant, a widely recognized therapeutic for insomnia, over a two-night period within a controlled sleep environment, exhibited a modest reduction in both amyloid-beta and tau proteins, which are known to precipitate in Alzheimer’s disease.

Despite the limited scope of this preliminary trial, involving a confined cohort of healthy adults, the findings originating from Washington University in St. Louis offer compelling evidence of the nexus between sleep quality and the molecular biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s pathology.

A concise video summary is provided below:

Disruptions in sleep architecture can manifest as an early harbinger of Alzheimer’s disease, often predating overt clinical manifestations such as memory impairment and cognitive deterioration.

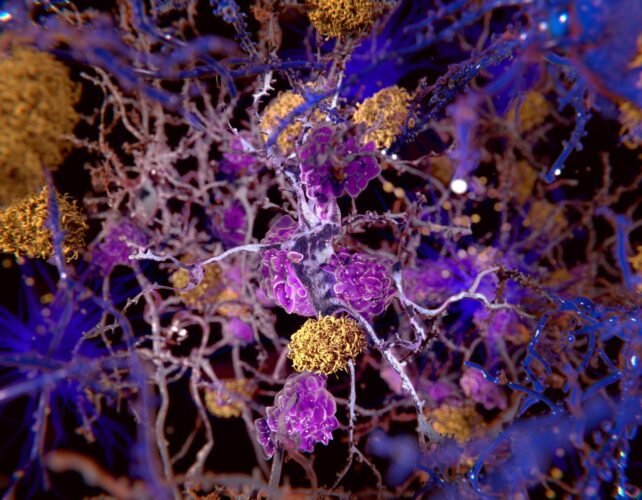

By the time initial symptoms become apparent, abnormal amyloid-beta levels are frequently approaching their zenith, congregating into formations known as plaques that impede neuronal function.

Although sleep aids might offer some benefit in this context, neurologist Brendan Lucey of Washington University’s Sleep Medicine Center, who spearheaded the research, cautioned that “it would be premature for individuals concerned about developing Alzheimer’s to interpret this as justification for nightly suvorexant use.”

The investigation, spanning a mere two nights, engaged 38 middle-aged participants who demonstrated no indications of cognitive compromise or pre-existing sleep disorders.

Sustained reliance on hypnotic medications is not an optimal strategy for individuals experiencing sleep deprivation, given the well-documented risk of dependency.

Furthermore, sleep-inducing pharmaceuticals may predispose individuals to more superficial sleep stages rather than the restorative deep sleep phases. This could prove disadvantageous, as prior investigations by Lucey and his associates have established a connection between diminished slow-wave sleep quality and elevated concentrations of tau tangles and amyloid-beta protein.

In their most recent endeavor, Lucey and his team sought to ascertain whether augmenting sleep through pharmacological means could effectively reduce tau and amyloid-beta levels within the cerebrospinal fluid that circulates throughout the central nervous system. Previous research indicates that even a solitary instance of disrupted sleep can precipitate an increase in amyloid-beta levels.

A cohort of volunteers, aged between 45 and 65, were administered either two distinct dosages of suvorexant or a placebo pill. Cerebrospinal fluid samples were collected one hour post-administration.

Subsequent sample collections were conducted at two-hour intervals over a 36-hour period, encompassing both sleep and wakefulness, to meticulously track alterations in protein concentrations.

Remarkably, no significant divergences in sleep architecture were observed between the groups. Nevertheless, amyloid-beta concentrations exhibited a reduction of approximately 10 to 20 percent in individuals receiving a standard insomnia-treating dose of suvorexant, in comparison to the placebo group.

The higher suvorexant dosage also induced a transient decrease in levels of hyperphosphorylated tau, a modified variant of the tau protein implicated in the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and subsequent neuronal demise.

However, this observed effect was specific to certain tau isoforms, and tau concentrations reverted to baseline levels within 24 hours of medication cessation.

Lucey expressed optimism regarding the potential therapeutic implications, stating, “If tau phosphorylation can be reduced, it is plausible that tangle formation and neuronal death might be lessened.” He further posited that “future investigations in older adults, involving extended treatment durations with sleeping pills, could potentially reveal a sustained impact on protein levels,” while also acknowledging the inherent drawbacks of such medications.

It is imperative to acknowledge that these insights are predicated on our evolving comprehension of Alzheimer’s disease etiology.

The predominant pathological hypothesis, positing that aberrant protein aggregates drive Alzheimer’s progression, has faced considerable skepticism recently. Decades of research focused on reducing amyloid levels have yielded no clinically effective drugs or therapies capable of preventing or retarding the disease. This has compelled researchers to re-evaluate prevailing models of Alzheimer’s pathogenesis.

In essence, while sleep aids may facilitate sleep induction for some individuals, their utility as a prophylactic measure against Alzheimer’s disease remains a speculative notion, contingent upon a now-questionable paradigm of Alzheimer’s pathology.

Notwithstanding, a growing body of evidence underscores the association between sleep disturbances and Alzheimer’s disease, a condition for which no definitive treatments are currently available. Lucey advocates for improved sleep hygiene and seeking professional intervention for sleep disorders, such as sleep apnea, as prudent strategies for enhancing overall brain health at any life stage.

“I am sanguine about the prospect of developing therapeutics that leverage the established connection between sleep and Alzheimer’s to forestall cognitive decline,” Lucey remarked. However, he candidly admitted, “We have not yet reached that milestone.”

The findings of this study were disseminated in the journal Annals of Neurology.