An ancient enigma has recently been unearthed from the profound depths of a Muna Island limestone cavern, situated off the coast of Sulawesi, Indonesia.

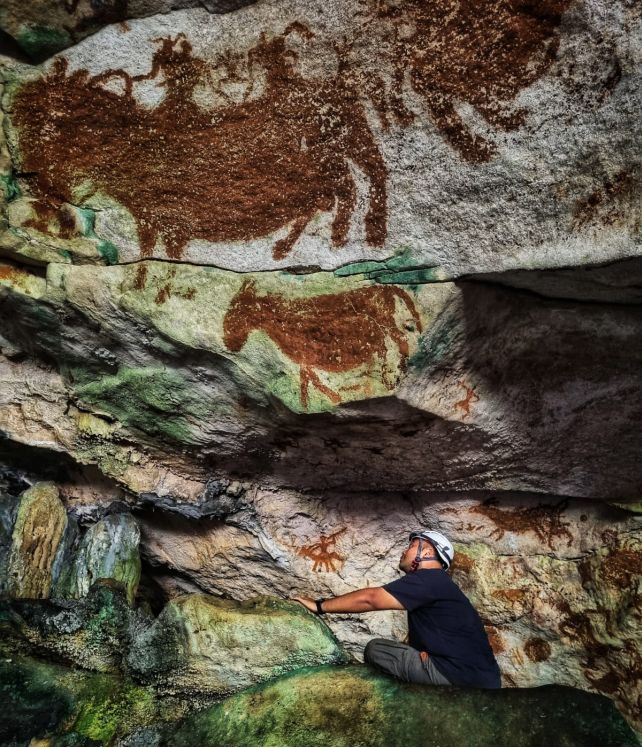

Within this subterranean environment, a dedicated team of archaeological researchers has brought to light human-fashioned rock engravings that predate any previously confirmed dated specimens, with an established minimum age of 67,800 years. These suggestive hand imprints, characterized by their distinctive, elongated digits, offer a critical piece of the intricate narrative concerning the initial dispersal of humankind across this region, occurring many millennia in the past.

“The phenomena we are observing in Indonesia are likely not a series of isolated occurrences, but rather a progressive unveiling of a substantially more profound and ancient cultural heritage that has, until very recently, remained obscured from our perception,” commented archaeologist Maxime Aubert, affiliated with Griffith University in Australia and a co-director of the investigative efforts, in a statement to ScienceAlert.

“The sheer volume and considerable antiquity of the rock art uncovered at this locale indicate that it was not a peripheral or transient site. Rather, it functioned as a vital cultural nexus, a territory where early Homo sapiens resided, traversed, and communicated abstract concepts through artistic expression for eons.”

In recent historical periods, both Sulawesi and the Indonesian sector of Borneo have emerged as unexpectedly significant locations for comprehending the early manifestations of human creativity and migratory patterns. In numerous instances, cave paintings were identified decades prior, yet investigators lacked the precise methodologies to accurately ascertain their age.

Owing to advancements in dating technologies, contemporary scientists can now affirm that certain of these artistic creations are considerably more ancient than previously theorized, with minimum age estimations surpassing 40,000 years and extending beyond 51,000 years.

“Each application of these analytical techniques to novel geographical areas reveals ages that significantly exceed prior expectations,” stated Aubert. “This suggests that the fundamental issue was not that early human populations began producing art spontaneously in a singular location, but rather that our investigatory focus has been misdirected, or our observational diligence has been insufficient.”

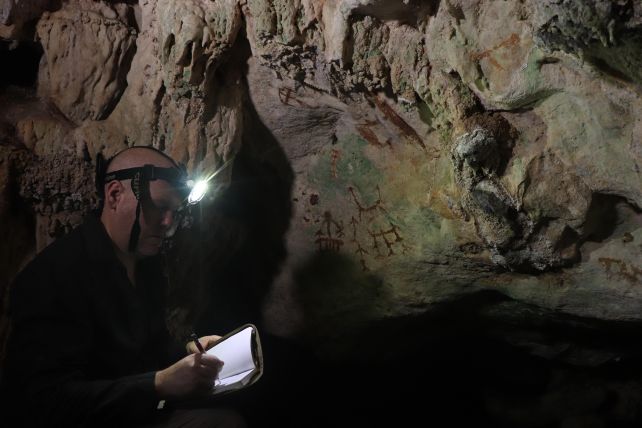

This most recent significant discovery was made within Liang Metanduno, a cavern long acknowledged for harboring prehistoric lithic artwork. Aubert and his associates were keen to ascertain the chronological placement of the artistic endeavors within this specific cave relative to the broader timeline of ancient art prevalent throughout the Indonesian archipelago.

Under fortunate circumstances, over immense temporal spans measured in millennia, a delicate layer of calcite accretes upon the artwork. This mineral coating precipitates from water that percolates across the rock’s surface. Such water frequently carries a minute quantity of uranium, which remains dissolved. Through the passage of time, uranium undergoes radioactive decay into thorium, a substance that is insoluble in water.

Given that the rate of uranium’s decay into thorium is precisely quantified, scientific practitioners can analyze the isotopic ratios of uranium and thorium within samples of this calcified overlay to establish its age.

Consequently, it is not the pigment itself that has been dated to 67,800 years ago, but rather the mineralized crust that formed atop it. The artwork situated beneath must, therefore, be at least this ancient.

This finding, when considered in conjunction with preceding evidence, implies that a significant proportion of the rock art within this region may be considerably more ancient than earlier estimations suggested. This, in turn, would necessitate a reevaluation of our understanding of Sulawesi—a pivotal waypoint for early human migrations en route to Australia.

“Artistic expression may have gained particular prominence as human populations expanded and intergroup interactions became more frequent,” Aubert posited.

“One can draw parallels to contemporary societal structures. Traffic control systems are essential in bustling metropolises, yet superfluous in small hamlets. Similarly, art, symbolic representations, and communal imagery likely served to articulate identity, foster a sense of belonging, and convey shared meaning as social networks grew in scale and complexity.”

For individuals engaged in archaeological pursuits, such manifestations of symbolic cognition hold significant weight, particularly concerning their temporal and geographical context. The recently dated artwork is situated along a hypothesized northern migratory pathway, believed to have been utilized by early anatomically modern humans during their transit through Island Southeast Asia towards Sahul, the landmass that united Australia and New Guinea during the Ice Age.

The discovery of evidence pointing to sophisticated artistic traditions along this migratory corridor helps to bridge a persistent hiatus between early archaeological sites on mainland Asia and the most nascent indications of human presence in Australia, suggesting that human colonization of Sahul may have occurred as early as 65,000 years ago.

Furthermore, this revelation generates a multitude of compelling inquiries. These include the potential for discovering additional rock art from this epoch in the surrounding territories, the mechanisms by which symbolic traditions disseminated and propagated, and the possibility of uncovering even earlier phases of this historical narrative.

“Our greatest source of excitement stems from the indication that early inhabitants of Southeast Asia were already articulating abstract concepts, defining their identities, and conveying meaning through visual imagery tens of thousands of years prior. These were not isolated experimental endeavors but integral components of a enduring cultural tradition,” Aubert conveyed.

“From our perspective, this discovery does not represent a conclusion to the narrative. Instead, it serves as an impetus for continued exploration.”