The high-fat, low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet has seen a surge in adherents recently, attributed to its perceived ability to facilitate rapid weight reduction. However, emergent investigations conducted on murine subjects indicate the potential for substantial adverse health consequences.

“I strongly advise individuals to consult a medical professional before embarking on a ketogenic dietary regimen,” stated physiologist Molly Gallop, the principal investigator of this research initiative.

The inquiry, spearheaded by a collective from the University of Utah, revealed that while the rodent participants adhering to a ketogenic-like dietary plan experienced a reduction in body mass, they simultaneously developed hepatic steatosis (fatty liver disease) and exhibited indicators of compromised glycemic control.

Although these observations require validation through human clinical trials, they imply that the physiological transformations instigated by the ketogenic diet might not universally confer metabolic advantages.

“We have reviewed studies focusing on short-term outcomes and solely on weight fluctuations, but comprehensive investigations examining long-term effects or broader metabolic health parameters have been notably scarce,” commented Gallop.

The designation “keto diet” originates from ketosis, the metabolic state it induces. This condition signifies a shift in the body’s primary energy source, favoring the oxidation of lipids over glucose. Achieving ketosis necessitates the consumption of foods elevated in fat content and diminished in carbohydrates.

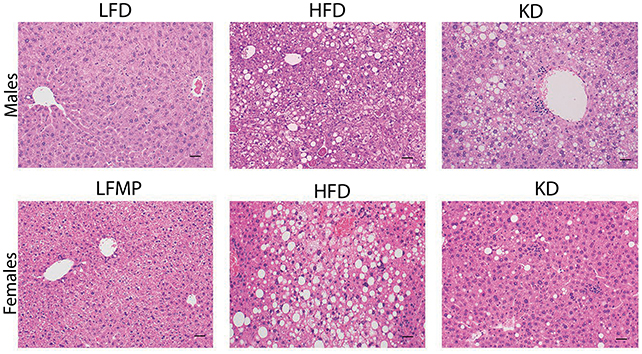

Within the scope of the contemporary investigation, researchers meticulously evaluated the physiological responses of mice maintained on four distinct dietary protocols for a minimum of nine months: a high-fat (Western-style) regimen; a highly fat-enriched, low-carbohydrate (keto-style) diet; a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet; and a low-fat diet supplemented with protein levels comparable to the keto-style diet.

In contrast to the control group on a standard high-fat diet, the mice consuming the ketogenic diet exhibited a statistically significant lesser degree of weight gain. Nevertheless, the male subjects on the ketogenic diet developed fatty liver disease and manifested impaired hepatic function, indicative of metabolic disorders.

“It is unequivocally evident that with an exceedingly high-fat intake, the excess lipids must be accommodated, typically accumulating within the bloodstream and the liver,” explained Amandine Chaix, a University of Utah physiologist and senior author of the study.

Both male and female mice on the ketogenic diet presented with suppressed levels of circulating glucose and insulin within a two-to-three-month timeframe. Subsequent analyses indicated that this phenomenon stemmed from a regulatory deficit, specifically inadequate insulin production by the pancreatic beta cells.

While further scientific inquiry is imperative to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and to ascertain the reasons for sex-specific hepatic complications, the research team posits that an excessive influx of circulating lipids may induce stress on pancreatic cells, thereby compromising insulin secretion.

Encouragingly, glycemic regulation returned to baseline levels in mice when the ketogenic diet was discontinued, suggesting the reversibility of these metabolic perturbations.

Historically, the ketogenic diet was formulated for the management of epilepsy and continues to be employed for its therapeutic efficacy in such cases. Ketosis bears a resemblance to certain metabolic adaptations observed during periods of starvation, compelling the organism to shift its primary fuel source from carbohydrates to lipids. Researchers theorize that this diminished glucose availability contributes to a reduction in seizure frequency.

Considering alternative applications of this dietary approach, the current study, alongside prior research, suggests that the potential benefits of weight reduction may be outweighed by an elevated risk of other health complications.