The great white shark represents an apex of evolutionary design. These magnificent marine predators navigate aquatic environments with remarkable fluidity, each measured, powerful undulation of their tail propelling a physique meticulously adapted for covert pursuit, swift propulsion, and peak operational efficiency.

From an aerial vantage point, their dark dorsal coloration provides effective camouflage against the profound cerulean depths, while their lighter ventral surface merges seamlessly with the sun-drenched expanse of the water’s surface when observed from below.

In a breathtaking instant, their placid glide transforms into a dynamic offensive maneuver, accelerating to velocities exceeding 60 kilometers per hour. The streamlined, torpedo-like silhouette cleaves through the water with minimal impediment. Subsequently, their most distinctive anatomical feature is brought to bear: multiple rows of exceptionally sharp dentition, exquisitely refined for their position at the zenith of the oceanic food web.

Ichthyologists have demonstrated a long-standing captivation with the dentition of white sharks. Fossilized dental specimens have been exhumed for protracted periods, and the robust, serrated morphology of these teeth is readily discernible in the maxillaries and bite impressions left by extant shark species.

However, until this recent investigation, a surprisingly limited understanding prevailed regarding a truly remarkable attribute of these impeccably formed structures: how their form varies across the dental arch and adapts to the evolving dietary requirements throughout an individual organism’s lifespan. Our latest research endeavor, disseminated in the journal Ecology and Evolution, was conceived to address this knowledge gap.

Evolution from Acicular Structures to Serrated Blades

Distinct shark taxa have developed specialized dentition synchronized with their nutritional profiles, encompassing acicular teeth ideal for ensnaring elusive cephalopods; broad, flattened molariform teeth for macerating benthic invertebrates; and sharply serrated dental elements for cleaving flesh and the adipose tissue of marine mammals.

Furthermore, shark dentition is essentially ephemeral; it undergoes perpetual regeneration throughout an individual’s existence, akin to a continuous assembly line that advances a new tooth into position approximately every few weeks.

The iconic white shark is predominantly recognized for its substantial, triangular, and serrated teeth, which are optimally suited for the capture and consumption of marine vertebrates such as pinnipeds, cetaceans, and marine mammals.

Nevertheless, a majority of juvenile specimens do not commence their predatory careers targeting pinnipeds. In actuality, their primary sustenance comprises piscine species and cephalopods, and they typically initiate the incorporation of marine mammals into their diet only upon reaching a body length of approximately 3 meters.

This observation precipitates a compelling inquiry: do the teeth emerging from the regenerative conveyor belt undergo morphological modifications to meet the specific challenges presented by diets during distinct developmental phases, analogous to how evolutionary processes sculpt teeth to align with the dietary preferences of disparate species?

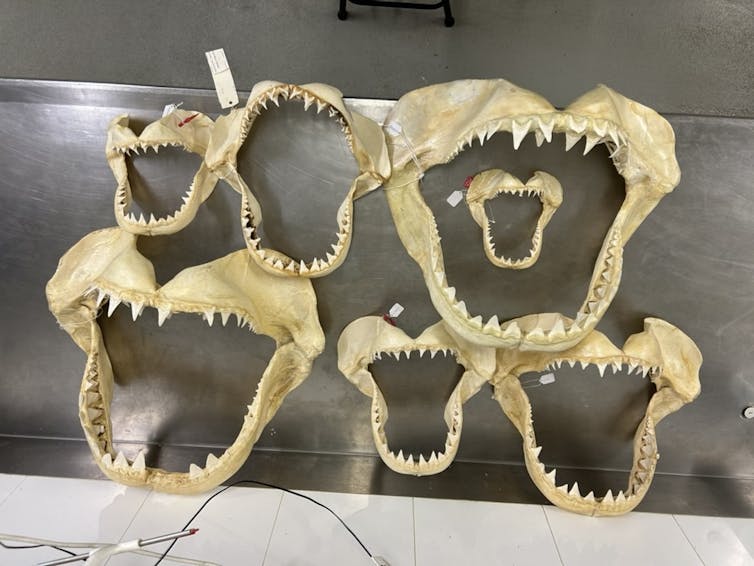

Prior scholarly investigations have predominantly concentrated on a constrained selection of teeth or single life-cycle stages. The deficiency lay in achieving a comprehensive, jaw-wide perspective on the transformation of dental morphology—not solely between the upper and lower jaws, but also from the anterior to the posterior regions of the oral cavity, and across successive stages of maturation from juvenile to adult.

Dental Morphology Evolves Throughout a Lifespan

Upon meticulous examination of dental specimens from nearly 100 great white sharks, discernible patterns became apparent.

Initially, the follicular morphology exhibits substantial variation across the dental arcade. The anterior six teeth on each side present as relatively symmetrical and triangular, rendering them exceptionally adept for grasping, impaling, or incising prey.

Beyond the sixth dental element, however, a significant morphological shift occurs. Teeth transition into a more blade-like configuration, better adapted for the maceration and shearing of flesh. This demarcation signifies a functional differentiation within the jaw, wherein distinct dental elements fulfill divergent roles during the act of predation, much like the specialized functions of human incisors in the anterior oral cavity and molars positioned posteriorly.

Even more noteworthy were the transformations observed as the sharks mature. At approximately 3 meters in body length, great white sharks undergo a profound dental metamorphosis. Juvenile dentition is characterized by a slenderness and often features diminutive lateral projections at the cervical margin of the tooth, termed cusplets, which facilitate the securement of smaller, more agile prey such as piscines and cephalopods.

As sharks attain a length approaching 3 meters, these cusplets recede, and the teeth progressively broaden, thicken, and develop serrations.

In numerous respects, this developmental trajectory mirrors a pivotal ecological transition. Juvenile sharks subsist on piscine species and smaller organisms that necessitate precision in capture and an enhanced capacity for gripping their diminutive forms. Larger specimens increasingly target marine mammals: sizable, swift-moving creatures that demand considerable cutting efficacy as opposed to mere grip.

Once great whites achieve this substantial size, they develop an entirely novel dental paradigm engineered for the dissection of dense musculature and even osseous structures.

Certain dental elements exhibit even greater specialization. The foremost two teeth on either side of the jaw, constituting the four central incisors, are conspicuously thicker at their base. These appear to function as the principal “impact” teeth, designed to absorb the substantial forces associated with the initial bite.

Concurrently, the third and fourth superior dental elements are marginally shorter and exhibit an oblique orientation, suggesting a specialized function in retaining struggling prey. Their dimensions and positioning may also be influenced by the underlying cranial architecture and the localization of critical sensory tissues involved in olfaction.

Furthermore, we identified consistent disparities between the maxillary and mandibular dentition. Mandibular teeth are shaped for the purpose of grasping and retaining prey, whereas maxillary teeth are architecturally designed for the cleaving and dismemberment of sustenance—a finely coordinated system that elevates the white shark’s bite into an exceptionally efficacious feeding apparatus.

A Life’s Narrative Encoded in Dentition

Collectively, these findings articulate a compelling biological narrative.

The dentition of great white sharks does not represent inert predatory instruments but rather serves as a living chronicle of an individual shark’s evolving lifestyle. Constant dental replacement not only compensates for exfoliated and compromised teeth but, crucially, facilitates adaptive modifications that track dietary shifts throughout its developmental trajectory.

This research contributes to a more profound appreciation of how great white sharks achieve their status as apex predators and the intricate calibration of their predatory mechanisms across their ontogeny.

It further underscores the significance of examining organisms as dynamic entities, shaped by the interplay of fundamental biological principles and behavioral adaptations. Ultimately, a great white shark’s dentition not only elucidates its feeding strategies but also reveals its fundamental identity at every juncture of its existence.–Below is The Conversation’s page counter tag. Please DO NOT REMOVE. —![]() — End of code. If you don’t see any code above, please get new code from the Advanced tab after you click the republish button. The page counter does not collect any personal data. More info: https://theconversation.com/republishing-guidelines —

— End of code. If you don’t see any code above, please get new code from the Advanced tab after you click the republish button. The page counter does not collect any personal data. More info: https://theconversation.com/republishing-guidelines —