Life within Earth’s intensely radioactive zones often exhibits peculiar characteristics, ranging from fungi that appear to flourish to a significant proliferation of vertebrate species when unhindered by human activity.

A contrasting narrative has unfolded at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station in Japan. Within the torus room, situated beneath the reactor, a microbial consortium has been quietly establishing itself in the absence of light ever since an earthquake inundated the facility with seawater in 2011.

Globally, organisms subjected to radiation typically develop subtle new attributes. What distinguishes the Fukushima microbial communities, as elucidated by scientific inquiry in 2024, is their apparent lack of specialized adaptations.

Their survival story is one of resilience, underpinned by a suite of inherent traits that enable them to persist under conditions that would prove detrimental to many other lifeforms.

The catastrophic Fukushima nuclear incident in March 2011 was a direct consequence of an undersea earthquake off the Japanese coast, which unleashed a tsunami that inundated the power plant located in Ōkuma town, Fukushima Prefecture, thereby causing core meltdowns.

The populace was promptly evacuated from the town, which has remained largely uninhabited since, with only restricted numbers of residents gradually returning in recent years, accompanied by scientific personnel and cleanup teams.

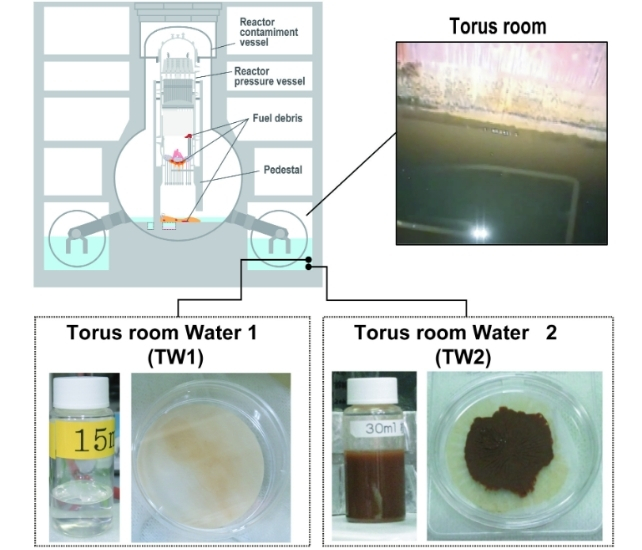

However, within the reactor containment structures, a novel challenge materialized. Substantial volumes of radioactive water accumulated, and within this aqueous medium, engineers observed formations strongly resembling microbial mats.

This observation is far from trivial. The decommissioning of a nuclear power facility constitutes an intricate, multi-decade endeavor that, as evidenced by scientific findings post the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear accident, can be significantly complicated by microorganisms. These biological entities can accelerate metallic degradation and impair water clarity, thereby impeding remediation efforts.

With this pertinent concern in mind, a research collective spearheaded by Keio University biologists Tomoro Warashina and Akio Kanai in Japan undertook the collection of samples from the highly irradiated water within the torus room – a safety containment vessel beneath the reactor designed to mitigate steam pressure. Subsequent genetic sequencing was performed on these samples to ascertain the microbial constituents present.

Based on prior investigations and discoveries of microbes at sites such as Chernobyl, the researchers anticipated identifying a prevalence of radiation-resistant species, including Deinococcus radiodurans – recognized as one of the most radio-resistant organisms known – and Methylobacterium radiotolerans.

An additional, crucial element of this situation warrants attention. The microbes were likely inhabiting biofilms, characterized as microbial aggregations encased in a gelatinous extracellular matrix. This matrix may have furnished a degree of protection against the ionizing radiation present in the chamber, according to the research team.

This finding merits careful consideration. Biofilms possess the capacity to accelerate metal corrosion, and if biofilm-forming microbes are indeed the predominant survivors in radioactive aquatic environments, this presents a foreseeable complication that must be addressed during the decommissioning of nuclear power facilities.

Remarkably, these bacteria did not require any specialized biological mechanisms to achieve this survival. The radiation did not compel life to adopt novel survival strategies or necessitate extremophile capabilities; instead, it fostered an exceptional milieu wherein relatively commonplace life forms could nevertheless subsist.

This phenomenon is quite extraordinary, even though it now presents a challenge that we cannot afford to overlook.

The findings of this research have been disseminated in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.