The United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow has concluded, with the Glasgow Climate Pact being formally adopted by all 197 participating nations.

While the 2015 Paris Agreement established the foundational structure for global climate action, Glasgow represented the inaugural significant assessment of this landmark diplomatic achievement approximately six years later.

Following two weeks of high-level pronouncements, extensive public demonstrations, and ancillary agreements concerning coal, the cessation of fossil fuel investments, and deforestation, what key insights can be extracted from the ultimately ratified Glasgow Climate Pact?

From the managed phase-out of coal to the exploitation of carbon market mechanisms, here is a synopsis of the critical takeaways:

1. Advances in Emission Reduction Imperfect, Falling Short of Requirements

The Glasgow Climate Pact signifies incremental progress rather than the transformative breakthrough essential for mitigating the most severe climate change repercussions.

The United Kingdom, in its capacity as host and thus President of COP26, aimed to “keep 1.5°C alive,” a more ambitious objective outlined in the Paris Agreement. However, at best, one can assert that the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C is precariously sustained – possessing a faint pulse but teetering on the brink of failure.

The stipulations of the Paris Agreement mandate that temperature increases be kept “well below” 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and that nations should “pursue efforts” to cap warming at 1.5°C. Prior to COP26, global projections indicated a warming trajectory of 2.7°C, based on existing national commitments and anticipated technological advancements.

The declarations made at COP26, including renewed commitments from several pivotal nations to curtail emissions within the current decade, have revised this forecast to a projected best estimate of 2.4°C.

Furthermore, an increased number of countries announced long-term net-zero emission targets. Noteworthy among these was India’s commitment to achieving net-zero emissions by 2070. Critically, the nation indicated an ambitious commencement by significantly expanding renewable energy capacity over the next ten years, aiming for it to comprise 50 percent of its total energy consumption, thereby reducing its 2030 emissions by one billion metric tons (from a present total of approximately 2.5 billion).

Nigeria, a rapidly developing economy, also put forth a pledge for net-zero emissions by 2060. Nations representing 90 percent of global GDP have now committed to attaining net-zero status by mid-century.

A world experiencing 2.4°C of warming remains demonstrably a considerable distance from the 1.5°C target. The persistent challenge lies in a near-term emissions deficit, as global emissions are predicted to plateau this decade rather than undergo the substantial reductions necessary to align with the 1.5°C trajectory advocated by the pact. A significant disparity exists between aspirational long-term net-zero objectives and the concrete strategies in place for achieving emissions reductions in the imminent future.

2. Opportunity for Enhanced Near-Term Reductions Persists

The finalized text of the Glasgow Pact acknowledges that current national climate action plans, referred to as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), fall considerably short of the requirements for achieving the 1.5°C objective. The pact also mandates that countries reconvene next year with updated and enhanced plans.

According to the Paris Agreement framework, the submission of updated climate plans is scheduled every five years. Given this, Glasgow, occurring five years after Paris (and delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic), was a critically important summit. The prospect of new climate plans being presented next year, rather than awaiting the subsequent five-year cycle, offers a reprieve for the 1.5°C goal, maintaining its viability for an additional twelve months and providing advocacy groups with an extended period to influence governmental climate policies. This also creates a precedent for requesting further NDC revisions from 2022 onwards, thereby accelerating ambition within the current decade.

The Glasgow Climate Pact further stipulates the staged reduction of unabated coal usage, alongside a phasing out of subsidies for fossil fuels. The language employed is less stringent than initially proposed, with the final wording advocating for a “phase down” rather than a complete “phase out” of coal, a concession influenced by a last-minute intervention by India, and the removal of subsidies deemed “inefficient.” Nevertheless, this marks the first occasion that fossil fuels have been explicitly addressed within a UN climate summit declaration.

Historically, nations like Saudi Arabia have successfully opposed the inclusion of such language. This represents a significant shift, finally acknowledging the imperative to rapidly diminish reliance on coal and other fossil fuels to effectively confront the climate emergency.

The long-standing taboo surrounding discussions on the eventual cessation of fossil fuel consumption has at last been broken.

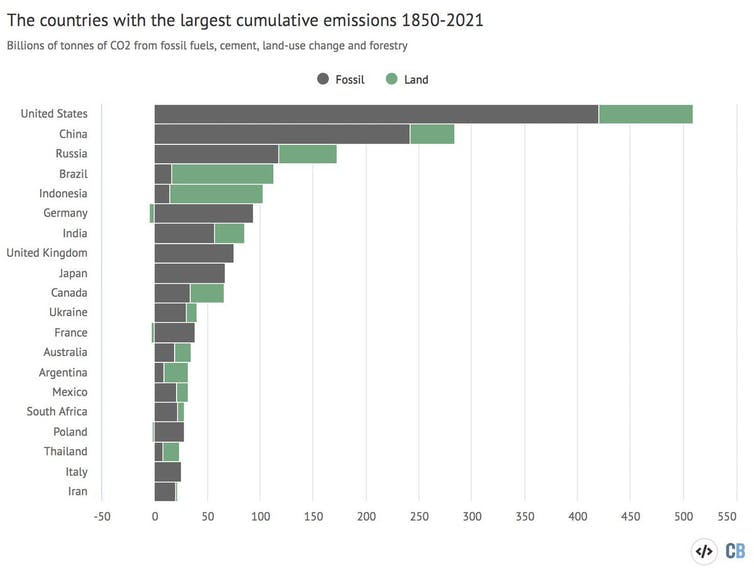

3. Affluent Nations Declined to Accept Historical Responsibility

Developing nations have been vocal in their demands for financial assistance to address “loss and damage,” encompassing the economic ramifications of climate-related events such as cyclones and rising sea levels. Small island states and countries susceptible to climate impacts contend that historical emissions from major polluting countries are the root cause of these advers within this context, necessitating dedicated funding mechanisms.

Developed nations, with leadership from the United States and the European Union, have consistently resisted acknowledging culpability for these losses and damages. They have also blocked the establishment of a new “Glasgow Loss and Damage Facility,” intended to support vulnerable nations, despite widespread support for such a mechanism from the majority of participating countries.

The UK has 1/20th the population of India, yet has emitted more fossil fuels. (CarbonBrief, CC BY-NC-SA)

The UK has 1/20th the population of India, yet has emitted more fossil fuels. (CarbonBrief, CC BY-NC-SA)

4. Potential for Carbon Market Mechanisms to Undermine Progress

Carbon markets could inadvertently provide a lifeline to the fossil fuel sector, enabling them to claim “carbon offsets” and continue operations with minimal disruption. A protracted series of negotiations concerning Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, pertaining to market-based and non-market approaches for carbon trading, was ultimately resolved after a six-year deliberation.

While the most egregious and substantial loopholes have been addressed, opportunities remain for countries and corporations to manipulate the system.

Beyond the formal COP proceedings, the implementation of significantly clearer and more robust regulations for corporate carbon offsets will be essential. Absent such stringent oversight, it is anticipated that non-governmental organizations and media outlets will uncover further instances of carbon offsetting malfeasance under this new framework, as new attempts to circumvent these remaining gaps will inevitably emerge.

5. Recognition Due to Climate Activists; Their Future Actions are Pivotal

It is evident that influential global powers are proceeding at an insufficient pace and have made a political choice to forgo a significant acceleration in both greenhouse gas emission reductions and the provision of financial aid to enable lower-income nations to adapt to climate change and transition away from fossil fuels.

However, considerable pressure is being exerted by their populations, particularly by climate advocacy groups. Indeed, Glasgow witnessed substantial demonstrations, with both the youth-led Fridays for Future march and the Saturday Global Day of Action drawing significantly larger crowds than anticipated.

Consequently, the subsequent actions of campaigners and the broader climate movement are of paramount importance. Within the United Kingdom, this will involve efforts to prevent the government from authorizing the exploitation of the new Cambo oil field located off the northern coast of Scotland.

Anticipate intensified action targeting the financing of fossil fuel projects, as activists seek to curtail emissions by restricting capital flow to the industry. Without the sustained advocacy of these movements, exerting pressure on nations and corporations, including at COP27 in Egypt, the objective of curbing climate change and safeguarding our invaluable planet will remain unattainable. ![]()