Ancient arrowheads unearthed from southern African strata still harbor remnants of toxic botanical agents, remarkably preserved for an estimated 60,000 years.

This groundbreaking finding substantially extends our understanding of the earliest documented use of poisoned projectiles, pushing the timeline back by tens of thousands of years.

While not instantaneously lethal, scientific analysis suggests the preserved toxins on these arrowheads possessed the potency to incapacitate a rodent within approximately 30 minutes. It is theorized that this tactic was employed to impede the escape of hunted game, thereby facilitating more efficient tracking and capture by early humans.

Prior to this revelation, the most ancient direct indicators of poisoned arrow usage originating from Africa were dated to the middle Holocene epoch, roughly 7,000 years ago.

“The application of poisons to weaponry represents a defining characteristic of sophisticated hunter-gatherer technological advancements,” stated an international consortium of researchers hailing from academic institutions in Sweden and South Africa.

“Beyond furnishing the inaugural confirmation of projectile poisoning in hunting practices during the late Pleistocene period in southern Africa,” the researchers further elaborated, “our discoveries contribute to a deeper comprehension of human adaptation and the complexities of technobehavioral development during an era marked by accelerated and cumulative innovation within the region.”

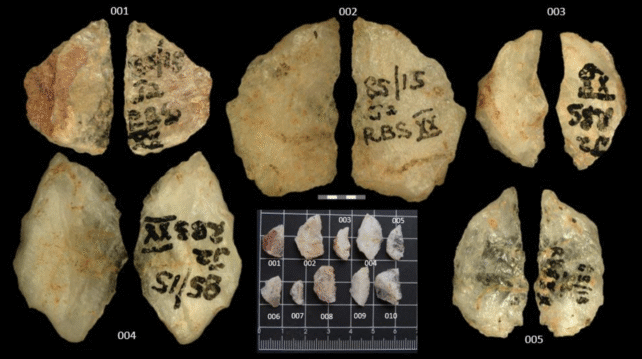

These primeval arrow tips were initially exhumed in 1985 from South Africa’s Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter, situated in the KwaZulu-Natal province. Despite their discovery, they remained cataloged and unexamined in a museum for several decades.

Current investigations, undertaken by scientists at Stockholm University, Linnaeus University, and the University of Johannesburg, have scrutinized 10 arrowheads from the recovered collection that displayed discernible residue.

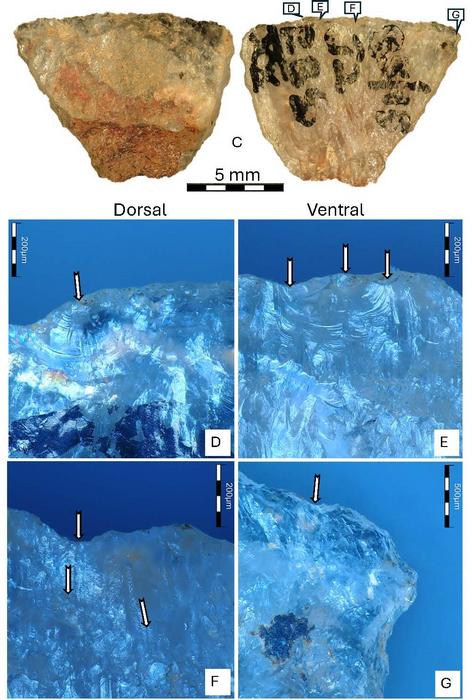

Employing an analytical methodology known as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, the international research team successfully identified botanical-derived toxic compounds on a subset of these arrowheads, marking the first concrete substantiation of poisonous plant matter on prehistoric hunting implements from the Pleistocene era.

The most probable botanical source identified is a prevalent plant species in southern Africa, classified as Boophone disticha. Historical records attest to its traditional utilization as an arrow poison by indigenous populations for the pursuit of fauna such as the springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis).

Certain scientific scholars had previously advanced the hypothesis that archery practices in southern Africa during the Late Pleistocene were likely augmented by the use of poisons. However, empirical evidence available up to this point has primarily relied on inferences drawn from mechanical wear patterns and ambiguous indicators of potential botanical residues.

Leading this recent investigative effort to validate this hypothesis was archaeologist Sven Isaksson, affiliated with Stockholm University in Sweden.

For an extended period, he and his research associates diligently pursued the extraction of definitive evidence of plant-based toxins from arrowheads dating back hundreds of years. They are now applying these refined methodologies to artifacts significantly older, extending back millennia.

Ultimately, analysis of five of the 60,000-year-old arrowheads revealed the presence of buphandrine – a toxic alkaloid derived from plants, which has also been detected in poisoned arrow fragments dating back 250 years.

Furthermore, another poisonous alkaloid, identified as epibuphanisine, was also detected on one of the ancient arrowheads. In their published report, Isaksson and his collaborators assert that this occurrence “cannot be coincidental.”

Both buphandrine and epibuphanisine are constituents of the foliage of B. disticha. Notably, out of the 269 historically recognized bowhunting communities in southern Africa, a significant majority, 168, are documented as employing poisoned projectiles.

The identification of these toxins on arrowheads approximately 60,000 years old strongly implies that this ingenious method of subsistence has a profoundly ancient lineage.

“Considering that poison operates through chemical mechanisms rather than physical force, the hunters must have possessed sophisticated capabilities in foresight, abstract thought, and causal reasoning,” the study’s authors conjecture.

Even preceding this remarkable discovery, one of the contributing authors, Marlize Lombard from the University of Johannesburg, had maintained that it was a reasonable postulation that hunter-gatherers in southern Africa were utilizing poisoned arrow tips around the 60,000-year mark, or potentially even earlier.

By that epoch, she underscored in a 2025 research publication, individuals in that geographical area had already acquired knowledge of and were utilizing plants for nutritional, medicinal, and insect-repelling purposes. Consequently, it is plausible they also possessed an understanding of and employed toxic flora.

More recently, scientific investigation has revealed evidence of Neanderthals creating complex adhesives derived from plant materials approximately 200,000 years ago.

The intellectual prowess of ancient hominins continues to astonish contemporary researchers.

The findings of this study have been disseminated in the esteemed journal Science Advances.