WASHINGTON (AP) – Individuals predisposed to staying awake late into the night may face detrimental effects on their cardiovascular well-being.

This assertion might appear counterintuitive, yet a comprehensive investigation has revealed that individuals exhibiting heightened activity during nocturnal hours – a period when the majority of the populace is either disengaging or already in slumber – demonstrate inferior overall cardiac health when contrasted with the general populace.

“It is not to say that those who are night owls are irrevocably destined for poor health,” articulated Sina Kianersi, a research fellow affiliated with Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, who spearheaded the investigation.

“The fundamental challenge lies in the discordance between one’s intrinsic biological clock and conventional daily timetables,” which consequently impedes the adherence to heart-protective practices.

Kianersi, who self-identifies as “somewhat of a night owl” and experiences heightened “analytical cognition” post 7 or 8 PM, suggested that this predicament is indeed rectifiable.

Cardiovascular ailments represent the foremost cause of mortality within the United States.

The American Heart Association proposes a compilation of eight critical determinants that warrant diligent consideration by all individuals aiming to enhance their cardiac health. These include: augmenting physical engagement; abstaining from tobacco; ensuring adequate rest and adopting a nutritious dietary regimen; and maintaining optimal control over one’s blood pressure, cholesterol levels, glycemic indices, and body mass.

How does one’s chronotype, specifically being a night owl, factor into this?

This phenomenon is intrinsically linked to the body’s circadian rhythm, our principal internal biological regulator. This rhythm orchestrates an approximate 24-hour cycle that dictates not only periods of somnolence and wakefulness but also ensures the synchronized functioning of organ systems, influencing variables such as heart rate, arterial pressure, stress hormone secretion, and metabolic processes.

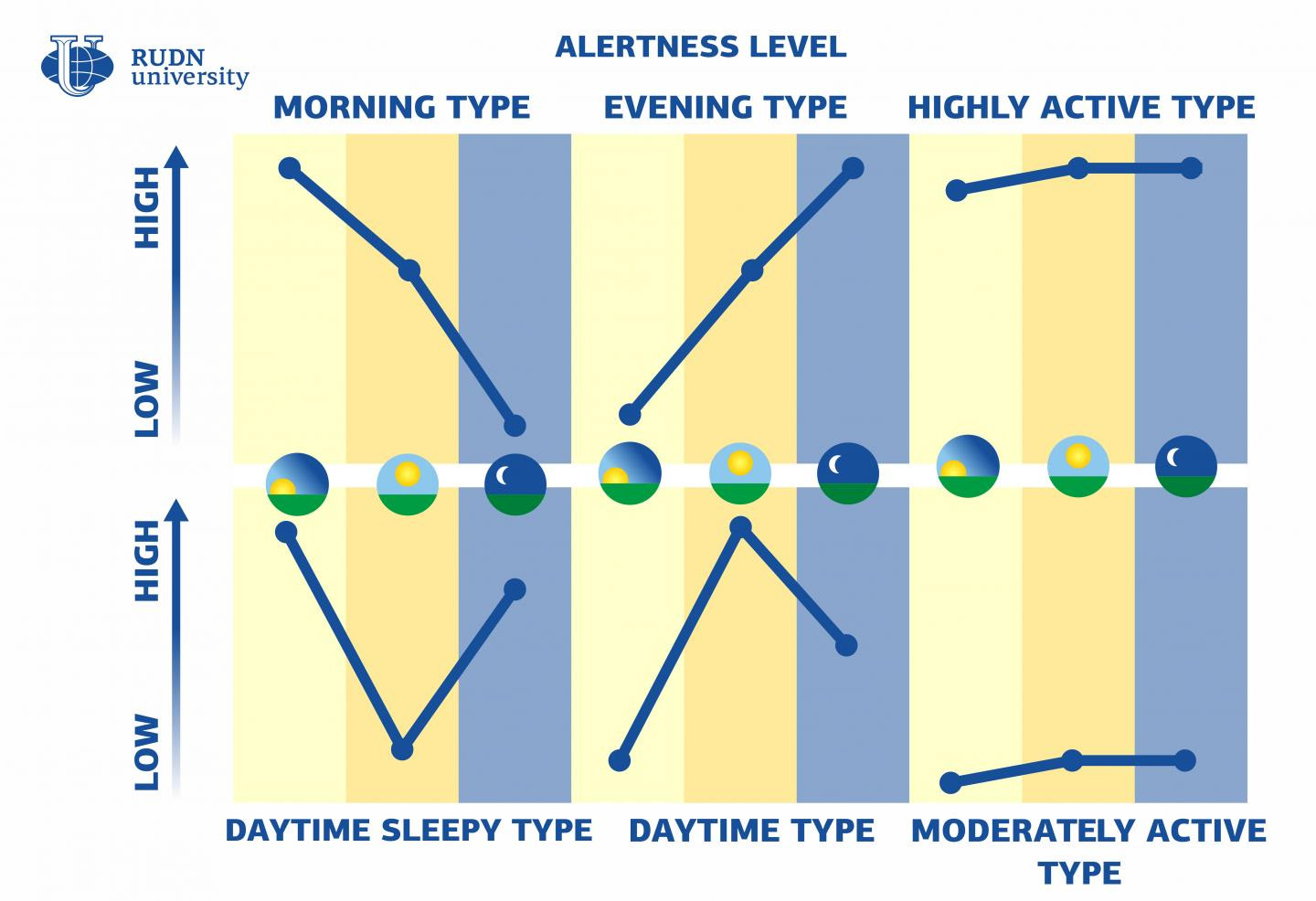

Each individual’s circadian rhythm exhibits unique variations. Kianersi pointed out that previous research had implied a correlation between a nocturnal disposition and an increased prevalence of health complications, alongside risk factors such as elevated rates of tobacco consumption and reduced levels of physical activity, when compared to individuals with more conventional sleep-wake patterns.

To further elucidate this connection, Kianersi’s investigative group meticulously monitored over 300,000 middle-aged and elderly participants enrolled in the UK Biobank, an extensive repository of health data encompassing individuals’ sleep-wake propensities.

Approximately 8 percent of these individuals characterized themselves as night owls, demonstrating greater physical and mental vigor in the late afternoon or evening, and remaining active well past customary bedtime.

Conversely, approximately a quarter identified as early birds, exhibiting peak productivity during daylight hours and retiring early. The remaining participants fell into the average category, occupying an intermediate position.

Over a period of 14 years, the night owl cohort experienced a 16 percent elevated probability of a first-time myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident in comparison to the general cohort, the investigators ascertained.

Furthermore, the night owls, particularly the female segment of this group, exhibited generally poorer cardiovascular health metrics, as assessed by their adherence to the American Heart Association’s eight key criteria, as the researchers disclosed on Wednesday in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

The principal contributing factors appear to be the adoption of health-compromising behaviors, including smoking, insufficient sleep, and inadequate dietary practices.

“The core issue arises from a night owl attempting to navigate a lifestyle structured for early risers. They may be compelled to commence their workday at an hour that conflicts with their innate biological rhythm,” explained Kristen Knutson of Northwestern University, who directed recent American Heart Association guidelines on circadian rhythms but was not involved in the current research.

This temporal discordance extends beyond mere sleep patterns.

For instance, metabolic processes, including insulin production for energy conversion from food, fluctuate throughout the diurnal cycle. Consequently, it may be more challenging for a night owl to effectively process a high-calorie breakfast consumed early in the day, during what would typically be their nocturnal period, Knutson noted. Moreover, nocturnal excursions can limit access to healthful culinary options.

Regarding sleep, even if achieving the recommended minimum of seven hours is not feasible, maintaining a consistent sleep-wake schedule can offer considerable benefits, as both she and Kianersi advised.

While the study was unable to investigate the activities of night owls during their periods of wakefulness when others are asleep, Kianersi indicated that a paramount measure for safeguarding cardiovascular health – applicable to night owls and the broader population alike – is the cessation of smoking.

“Concentrate on fundamental principles, rather than striving for absolute perfection,” he reiterated, emphasizing advice that is universally beneficial.