Annually, on the 14th of March, a tradition has emerged among enthusiasts of numbers and mathematical scholars to pause and contemplate the most renowned irrational quantity: pi.

This figure, pronounced like the baked good and denoted by the symbol π, is commonly represented by the digits 3.14. This ostensibly unpretentious constant now serves as a poignant reminder of how practical, poetic, and deeply significant mathematics can be in our contemporary existence.

The question arises: why does pi receive such acclaim, while other fundamental constants like e or the golden ratio are not similarly feted? Should our focus perhaps shift towards commemorating tau day?

While not everyone concurs with the high regard in which pi is held, its inherent appeal remains undeniable.

The Nature of Pi

Pi (π) is a mathematical constant that encapsulates the relationship between a circle’s circumference and its diameter. It is classified as an irrational number and is typically rounded to two decimal places, yielding 3.14.

Curious about its complete value? Given its unending nature, enumerating it fully would be an extensive undertaking. Nevertheless, here are the initial 200 decimal places, presented as a song for your enjoyment. Feel free to join in the rendition!

The Greek letter P, a designation for pi, was adopted in the 18th century by the Welsh mathematics educator William Jones. It is widely believed that his choice was motivated by the word ‘periphery’.

The adoption of the symbol pi represented an intent to signify more than just a numerical value. Prior to its formal introduction in the early 18th century, this quantity was expressed through various phrases and fractions, none of which effectively conveyed the essence of an incomprehensible, infinitely extending sequence of non-repeating digits.

Jones may have entertained the notion that “‘the exact proportion between the diameter and the circumference can never be expressed in numbers”, but it was not until the 1760s that the accomplished Swiss mathematician Johann Lambert provided a definitive proof of its irrationality.

Historical Calculation of Pi

It appears that since humanity’s earliest engagement with the geometry of circles, there has been an implicit understanding that approximately three diameters are required to encompass the circumference, irrespective of the circle’s dimensions.

Evidence of this ratio can be found within the mathematical records of the ancient Babylonians, dating back approximately 4,000 years. They recognized that the perimeter of a hexagon inscribed within a circle was equivalent to six times its radius, leading to an approximate value of 3.125.

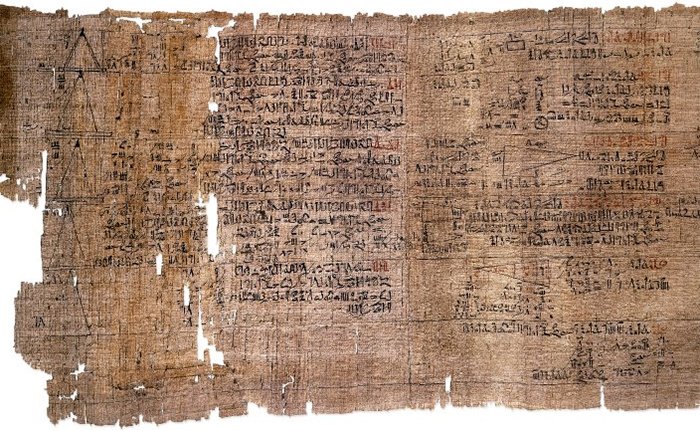

The Rhind Papyrus, a document originating from Ancient Egypt around 1650 BCE, proposes a method equivalent to stating that if one-ninth of a diameter is subtracted and a square is constructed upon the remainder, the area of this square would be equal to that of the circle. This calculation equates to a value of 3.16049.

(British Museum Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan/PD)

(British Museum Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan/PD)

Archimedes of Syracuse also made significant contributions to the problem. By employing polygons, much like the Babylonians, and extrapolating their sides, he determined a more theoretical range for pi, falling between 3 and 1/7, and 3 and 10/71.

The Enduring Appeal of Pi

As a universal constant for all circles, pi functions as an axiom—a foundational principle—that facilitates the description of a wide array of phenomena and concepts across the fields of physics and geometry.

This intrinsic property renders it invaluable for a vast spectrum of applications aimed at analyzing and characterizing the natural world, from the irregular paths of meandering rivers to the intricate structures of atoms.

Remarkably, pi can appear in unexpected contexts, even where circles are not immediately apparent. For instance, the probability that any two integers share no common positive divisors—a state known as being relatively prime—is precisely 6/π^2.

Beyond its utilitarian and mathematical merits, pi has captivated the public imagination through sheer aesthetic appeal and poetic resonance. Larry Shaw, a physicist and staff member at San Francisco’s Exploratorium, observed during a staff retreat in 1988 that the date March 14 mirrored the initial three digits of pi: 3.14.

This observation spurred the creation of a day dedicated to the celebration of science and mathematics: Pi Day, which has since become a global observance. Over three decades later, the day is celebrated worldwide with the dissemination of pi trivia, engaging mathematical challenges, and the preparation of the quintessential circular dessert: the pie.

(ScienceAlert)

(ScienceAlert)