Within an ancestral rock overhang situated in the core of Malawi, excavators have unearthed the globe’s most ancient testament to an adult funeral pyre.

The calcined remnants, dating back 9,500 years, indicate that the departed was a female, estimated to be between 18 and 60 years of age at the time of her demise. Her physical form underwent meticulous preparation for incineration upon a substantial pyre that sustained combustion for numerous hours. This elaborate process was integral to a deliberate funerary observance at a locale that had already functioned as a nexus for death rituals for a minimum of 8,000 years.

This represents “the earliest manifestation of committed cremation in Africa, and the world’s most venerable in situ adult pyre,” according to a research contingent spearheaded by anthropologist Jessica Cerezo-Román from the University of Oklahoma.

This remarkable finding significantly broadens our comprehension of hunter-gatherer funeral customs, demonstrating that their commemorative practices could possess a far greater degree of intricacy than was heretofore presumed.

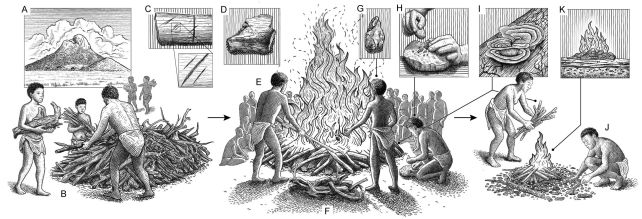

The observance necessitated meticulous orchestration and construction, alongside a substantial allocation of resources to procure and sustain the considerable volume of combustible material required to maintain the pyre’s fiery duration for extended periods.

The sustained utilization of this particular location further suggests the existence of a collective social consciousness, potentially encompassing forms of ancestor homage that were previously considered negligible among nomadic foraging communities.

The solemnity with which humanity confronts mortality has been evident for countless millennia. The earliest reliably dated instance of deliberate interment is recorded 78,000 years ago. Earlier indications of intentional burials, possibly attributable to other hominin species, remain a subject of intense scholarly debate.

Regarding cremation, concrete evidence becomes less prevalent prior to approximately 7,000 years ago, particularly within hunter-gatherer societies. The most ancient human remains exhibiting signs of cremation, discovered interred at Lake Mungo in Australia, are dated to around 40,000 years ago, though no pyre structure was identified.

The most definitively established in situ pyre—where the remains are discovered at the precise location of the cremation event, atop a specially constructed combustion platform—dates back to 11,500 years ago in what is now Alaska, representing a funerary rite for a young child.

Following this, no further evidence of pyre-based cremation emerges until approximately 7,000 years ago at Beisamoun, in the southern Levant region.

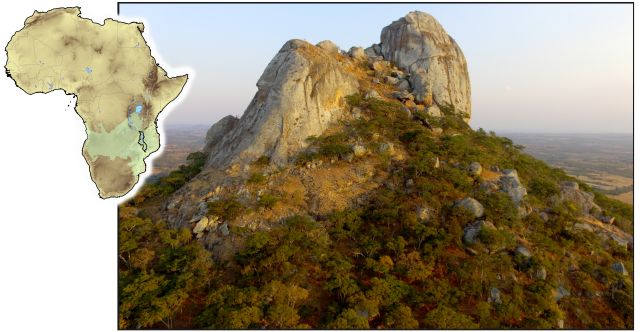

At the base of Mount Hora in Malawi lies an archaeological locality known as HOR-1, which bore witness to human activity spanning an estimated 21,000 years. Between 16,000 and 8,000 years ago, it served as a venue for mortuary practices. Excavators have identified the skeletal remains of a minimum of 11 individuals at this site.

Only one individual exhibits definitive signs of cremation prior to interment. This individual, officially classified as Hora 3, and for whom only fragmentary skeletal elements—including long bones, sections of the vertebrae and pelvis, and some phalanges—were recovered, alongside a substantial deposit of ashy residue, collectively offer a vivid depiction of her funeral rites.

The thermal degradation and fracturing observed on the bones signify their prolonged exposure to elevated temperatures. Furthermore, incised marks on the skeletal fragments suggest that specific portions of Hora 3’s anatomy were severed prior to the cremation process.

The chromatic variations present on the bones also indicate they were repositioned during the incineration, potentially as the fire’s intensity was augmented and the material agitated.

The absence of any cranial fragments or dental elements belonging to the woman suggests that her head might have been detached antecedent to incineration. This practice, for which corroborating evidence has been found at other archaeological locales within the region, is presumed to be “associated with mortuary customs linked to commemoration, collective memory, and the veneration of ancestors, which involved the post-mortem manipulation and preservation of bodily parts,” the investigators articulate in their published report.

Concurrently, the dimensions and composition of the ash accumulation align with a pyre comprising no less than 30 kilograms (66 pounds) of deadwood, herbage, and foliage—a considerable procurement of resources that would have sustained an enduring conflagration.

Stratified ash deposits overlying the exhumed remains further propose that the identical spatial locus was utilized for fires over several centuries subsequent to the cremation event.

The researchers interpret this as indicative that the site likely functioned as a “persistent place,” potentially tethered to territorial claims and reflecting ancestral linkages within a landscape that continues to be of significant natural grandeur.

“The historical trajectory of substantial fire construction at this particular site, the sustained effort invested in the cremation observance, and the subsequent extensive burning episodes collectively signify a deeply ingrained tradition of repeatedly returning to and utilizing the location, intricately interwoven with the cultivation of memory and the establishment of a ‘persistent place’,” they assert.

“These practices underscore sophisticated mortuary and ceremonial activities with origins predating the development of agriculture, and they challenge conventional presuppositions regarding collaborative efforts at a community level and the formation of significant locales within tropical hunter-gatherer societies.”