The identification of two potent plant alkaloids, buphandrine and epibuphanisine, has been confirmed by archaeologists on implements unearthed from Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter, located in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. These implements, characterized as backed microliths, were retrieved from strata dating back approximately 60,000 years. This temporal placement signifies the application of projectile poison well into the Late Pleistocene epoch.

“This represents the most ancient direct substantiation of human utilization of arrow poison,” stated Professor Marlize Lombard of the University of Johannesburg.

“It suggests that our southern African antecedents not only innovated the bow and arrow considerably earlier than previously understood but also possessed an understanding of how to harness natural chemistry to enhance hunting efficacy.”

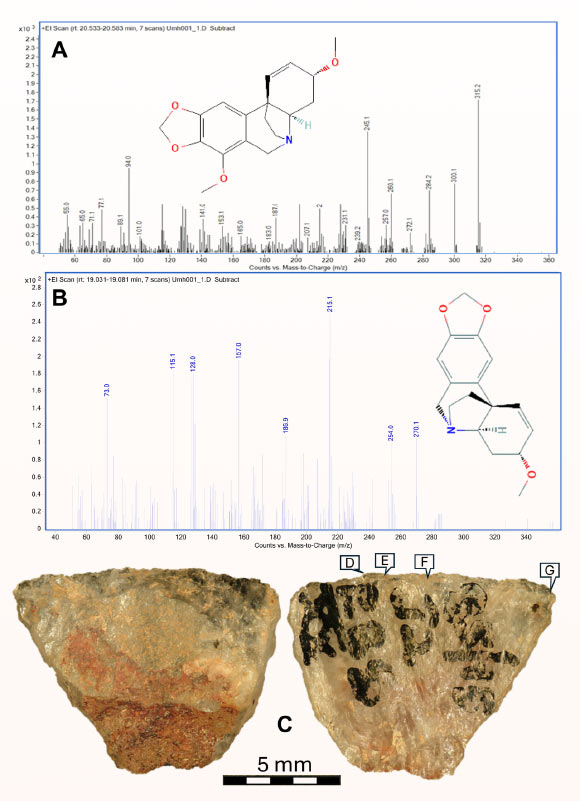

Professor Lombard and her research team subjected ten quartz microliths to analysis of their residual matter, employing gas chromatography-mass spectrometry techniques.

Their investigation revealed the presence of two toxic plant alkaloids—buphanidrine and epibuphanisine—on five of the examined specimens.

These specific chemical compounds are exclusively derived from the Amaryllidaceae plant family, which is native to the southern African region.

The most probable progenitor of these alkaloids is a particular species known as Boophone disticha, a plant historically linked to arrow poisons.

The observed residue patterns indicate that the microliths from Umhlatuzana were affixed transversely and functioned as projectile tips.

On certain artifacts, visible traces of the poison residue were discernible along the dorsal, reinforced section, pointing towards the incorporation of toxic substances into an adhesive used to secure the stone point to the arrow shaft.

Microscopic evidence of impact fractures and abrasions along the edges aligned with their inferred use as transversely mounted arrowheads.

To validate their discoveries, the investigators conducted comparative analyses between the prehistoric residues and poisons extracted from arrowheads collected in South Africa during the 18th century.

“The identification of identical poison traces on both ancient and more recent arrowheads was a pivotal finding,” commented Professor Sven Isaksson from Stockholm University.

“Through meticulous examination of the chemical composition of these compounds, we were able to ascertain that these particular substances exhibit sufficient stability to persist in the ground over such extended durations.”

This groundbreaking revelation extends the documented timeline for the use of poisoned weaponry significantly further into antiquity.

Prior to this research, the earliest definitive evidence of arrow poison dated to the middle Holocene epoch—several millennia ago. Conversely, findings from Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter unequivocally demonstrate the existence of such technology at least 60,000 years ago.

The research authors posit that poisoned arrows were not intended for immediate lethality but rather relied on toxins designed to gradually incapacitate prey, thereby enabling hunters to pursue quarry over considerable distances.

“Employing arrow poison necessitates foresight, endurance, and a comprehension of causal relationships,” stated Professor Anders Högberg of Linnaeus University.

“This clearly signals a sophisticated cognitive capacity in early human populations.”

This remarkable discovery is detailed in a publication released on January 7 in the esteemed journal Science Advances.

_____

Sven Isaksson et al. 2026. Direct evidence for poison use on microlithic arrowheads in Southern Africa at 60,000 years ago. Science Advances 12 (2); doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adz3281