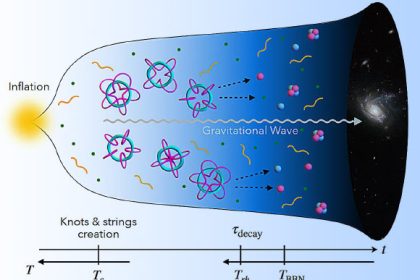

Borrowing an ingenious technique utilized by astronomers to capture images of a black hole, researchers at the University of Connecticut have engineered a lens-free imaging sensor capable of achieving three-dimensional resolution below the micron scale, a development poised to revolutionize domains ranging from forensic analysis to distant environmental monitoring.

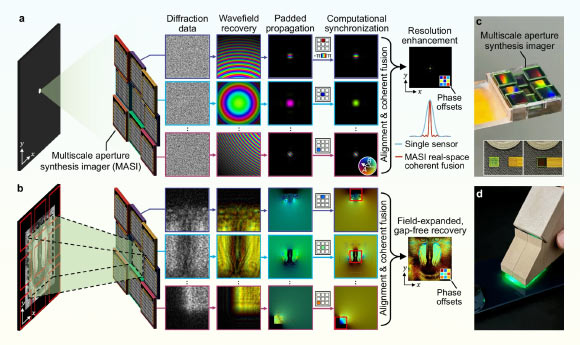

Operating principle and implementation of MASI. Image credit: Wang et al., doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-65661-8.

“At the core of this significant advancement lies a persistent technical challenge,” remarked Professor Guoan Zheng from the University of Connecticut, the principal investigator for the study.

“Synthetic aperture imaging functions by coherently aggregating measurements acquired from an array of spatially separated sensors, thereby approximating the performance of a substantially larger imaging aperture.”

This methodology is practical in radio astronomy due to the considerably longer wavelengths involved, which facilitate precise temporal synchronization among the sensors.

However, when dealing with visible light wavelengths, where the dimensions of interest are vastly smaller, the stringent synchronization demands become exceedingly difficult, if not practically impossible, to fulfill physically.

The Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager (MASI) fundamentally reorients this challenge.

Instead of enforcing absolute physical synchrony among multiple optical sensors, MASI allows each sensor to record light measurements independently. Subsequently, sophisticated computational algorithms are employed to synchronize the collected data retrospectively.

“This is analogous to assigning several photographers to capture the identical scene, not as conventional photographs, but as raw data representing the wave properties of light. Subsequently, software is utilized to seamlessly combine these independent recordings into a single image of exceptional resolution,” explained Professor Zheng.

This computational approach to phase synchronization obviates the necessity for rigid interferometric configurations, which have historically impeded the practical implementation of optical synthetic aperture systems.

MASI introduces two paradigm-shifting departures from conventional optical imaging techniques.

Rather than employing lenses for light focusing onto a sensor, MASI utilizes an arrangement of patterned sensors strategically positioned within a diffraction plane. Each of these sensors captures raw diffraction patterns – essentially, the manner in which light waves diverge after interacting with an object.

These diffraction measurements encapsulate both amplitude and phase information, which are subsequently retrieved through the application of computational algorithms.

Once the complex wavefield for each sensor is successfully extracted, the system digitally interpolates and computationally propagates these wavefields back towards the object plane.

A computational phase synchronization mechanism then iteratively refines the relative phase discrepancies of each sensor’s dataset to maximize the collective coherence and energy within the unified reconstructed image.

This particular step represents the pivotal innovation: by optimizing the integrated wavefields through software rather than relying on physical sensor alignment, MASI transcends the diffraction limit and other constraints inherent to traditional optical systems.

This establishes a virtual synthetic aperture that surpasses the dimensions of any individual sensor, thereby enabling sub-micron resolution and extensive field coverage without the reliance on lenses.

Standard lenses, whether incorporated into microscopes, cameras, or telescopes, compel designers to accept compromises.

To resolve finer details, lenses must be positioned in close proximity to the subject, often within millimeters, which restricts the working distance and renders certain imaging tasks infeasible or intrusive.

The MASI methodology completely foregoes the use of lenses, capturing diffraction patterns from distances of several centimeters and reconstructing images with resolutions down to the sub-micron level.

This is comparable to being able to discern the intricate striations on a human hair from across a desk, rather than needing to bring it within inches of one’s eye.

“The prospective applications for MASI are extensive and span numerous disciplines, including forensic science, medical diagnostics, industrial quality control, and remote sensing,” stated Professor Zheng.

“However, what is particularly exhilarating is its inherent scalability. Unlike conventional optics, where complexity escalates exponentially with size, our system exhibits linear scaling, potentially facilitating the creation of expansive sensor arrays for applications we have yet to envision.”

The research paper authored by the team was disseminated in the esteemed journal Nature Communications and can be accessed via the following link: paper.

_____

R. Wang et al. 2025. Multiscale aperture synthesis imager. Nat Commun 16, 10582; doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-65661-8