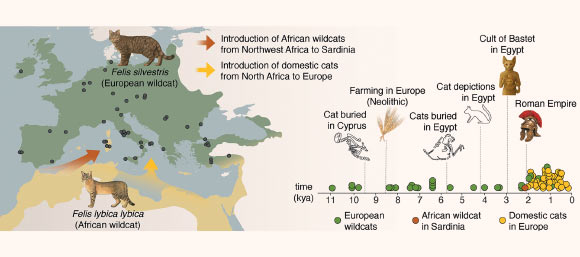

The lineage of the domestic cat (Felis catus) can be traced back to the African wildcat (Felis lybica lybica). Its widespread presence alongside human civilization attests to its remarkable adaptability to environments shaped by humankind. The precise geographical origin of domestic cats—whether it was the Levant, Egypt, or another area within the African wildcat’s natural habitat—remains a subject of debate. A collaborative international scientific endeavor, spearheaded by researchers from the University of Rome Tor Vergata, has now accomplished the full sequencing of genomes from 87 specimens, encompassing both ancient and contemporary felines. Their discoveries cast doubt on the prevailing theory of cats being introduced to Europe during the Neolithic period, instead indicating their arrival several millennia later.

The genetic analyses of ancient feline samples sourced from archaeological excavations throughout Europe and Anatolia (represented by circles on the map) have indicated that domestic cats were brought to the European continent from North Africa approximately 2,000 years ago. This timing significantly postdates the commencement of the Neolithic era in Europe. Furthermore, the African wildcat populations found on Sardinia are derived from a separate wildcat lineage originating in Northwest Africa. Image credit: De Martino et al., doi: 10.1126/science.adt2642.

The historical trajectory of the domestic cat is extensive and intricate, though still marked by certain ambiguities.

Genetic investigations confirm that all extant cat breeds have evolved from the African wildcat, a species currently indigenous to North Africa and the Near East.

Nonetheless, the scarcity of archaeological evidence and the challenges inherent in differentiating between domestic and wild felines based solely on skeletal remains have created considerable lacunae in our comprehension of the genesis and propagation of early domesticated cats.

“The temporal framework and the specific conditions surrounding feline domestication and their subsequent dissemination remain uncertain due to the restricted number of ancient and modern feline genomes subjected to analysis thus far,” remarked Dr. Marco de Martino of the University of Rome Tor Vergata, alongside his research associates.

“Persistent questions exist regarding the historical geographical ranges of African and European wildcats and the potential for genetic interbreeding between them.”

“A recent scholarly investigation highlighted that historical genetic exchange could potentially skew the reconstruction of feline migratory patterns, particularly when relying on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA).”

“The origins of the African wildcat populations residing on the Mediterranean islands of Sardinia and Corsica are also a matter of unresolved inquiry.”

“Current data suggests that these populations are not simply feral domestic cats but rather represent a distinct, independent wildcat evolutionary line.”

To elucidate these matters, the research team undertook an in-depth analysis of the genomic data from 70 ancient cat specimens recovered from archaeological sites across Europe and Anatolia, complemented by the genomes of 17 contemporary wildcats sampled from Italy (including Sardinia), Bulgaria, and North Africa (Morocco and Tunisia).

In contradiction to prior research findings, their study concluded that domestic cats most likely originated from North African wildcats, rather than from populations in the Levant. Furthermore, they posited that true domestic cats did not emerge in Europe and Southwest Asia until several thousand years subsequent to the Neolithic period.

Earlier feline presence in Europe and Türkiye was genetically attributable to European wildcats, signifying ancient hybridization events rather than genuine early domestication.

Following their introduction, North African domestic cats rapidly expanded their range across Europe, frequently following the pathways of Roman military movements, and had reached Britain by the 1st century CE.

Moreover, the recent investigation reveals that Sardinian wildcats, encompassing both ancient and modern specimens, exhibit a closer genetic relationship to North African wildcats than to domestic cats. This finding implies that humans facilitated the translocation of wildcats to islands where they did not naturally occur, thereby refuting the notion that they are descendants of an early feral domestic cat population.

“Our research redefines the timeline of feline dispersal by identifying a minimum of two distinct introduction events into Europe,” the scientists stated.

“The initial dispersal event likely involved wildcats originating from Northwest Africa that were transported to Sardinia, subsequently establishing the island’s current wild population.”

“A separate, as-yet-unidentified population in North Africa served as the source for a second dispersal event, occurring no later than 2,000 years ago, which ultimately established the genetic makeup of modern domestic cats found in Europe.”

The groundbreaking discoveries made by the research team are published this week in the esteemed journal Science.

_____

M. De Martino et al. 2025. The dispersal of domestic cats from North Africa to Europe around 2000 years ago. Science 390 (6776); doi: 10.1126/science.adt2642