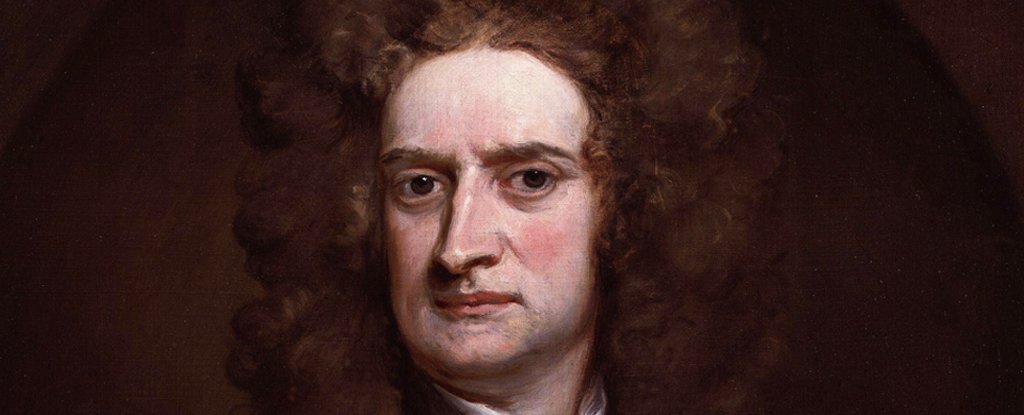

Undeniably, contemporary science owes a considerable debt to Sir Isaac Newton, the eminent 17th-century English polymath. It’s not without good reason that an entire unit of measurement for force bears his name.

However, if a sense of inadequacy stems from your own period of isolation not yielding the prodigious output attributed to his, offer yourself some leniency. His so-called Annus Mirabilis was perhaps not as ‘miraculous’ as commonly portrayed.

In a year marked by a dearth of inspiration and an abundance of wistful gazes out of windows, yearning for a 2021 with less plague, societal discord, and political division, it is understandable why certain prominent figures in the scientific community might seek to find a silver lining in current events.

Earlier this year, Neil deGrasse Tyson shared a fascinating historical anecdote, delivered in his characteristic witty style, via Twitter.

When Isaac Newton stayed at home to avoid the 1665 plague, he discovered the laws of gravity, optics, and he invented calculus.

It’s rumored that there was a strict “No TV” rule in his household. pic.twitter.com/0uLmmb65s5— Neil deGrasse Tyson (@neiltyson) March 31, 2020

Not to be outdone, Richard Dawkins recently reiterated this same piece of historical trivia.

In 1665 Cambridge University closed because of plague. Isaac Newton retreated to rural Lincolnshire. During his 2 years in lockdown he worked out calculus, the true meaning of colour, gravitation, planetary orbits & the 3 Laws of Motion. Will 2020 be someone’s Annus Mirabilis?

— Richard Dawkins (@RichardDawkins) September 17, 2020

For added context, Isaac Newton was a young undergraduate, barely in his early twenties, attending Trinity College at the University of Cambridge when the bubonic plague necessitated the closure of his institution in 1665.

Consequently, he returned to his family home, where for approximately the following year, he dedicated his leisure time to a period of remarkable intellectual output, marked by a series of profound revelations. The precise nature of his work during this time varies depending on the source, but commonly includes significant advancements in the understanding of gravity, forces, optics, and calculus.

This narrative has been frequently disseminated over the course of many years. However, in light of our collective firsthand experience with a historically significant pandemic, Newton’s story has resurfaced with renewed prominence.

The appeal of an inspiring account of scientific breakthrough is universal, and figures within the scientific community are not immune to its allure. Nevertheless, when recounting the events of Newton’s ‘miraculous year,’ certain crucial details can often be marginalized to underscore the singular genius of the individual.

Newton himself may have retrospectively viewed this period as exceptionally fruitful. A publication from 1888 quotes him as identifying 1665 and 1666 as years of significant inventive activity, stating, “For in those days I was in the prime of my age for invention.”

Even setting aside his personal testimony, it remains highly probable that his time was extensively devoted to advanced mathematical studies. He compiled a comprehensive treatise on his learning in October 1666, which contained the nascent concepts of what is now recognized as calculus. This hardly suggests a period of intellectual idleness.

It is precisely at this juncture that the overlooked details assume considerable significance. Historian of science Thony Christie meticulously elaborates on these finer points on her blog, The Renaissance Mathematicus, a resource that warrants careful perusal.

Far from ‘inventing calculus’ in isolation, Newton’s efforts during that period involved synthesizing centuries of prior scholarship on the subject, meticulously compiling and extending existing theories in a project that extended well beyond those few plague-ridden years.

This perspective does not aim to diminish the magnitude of the breakthroughs achieved or to downplay Newton’s profound contributions to the field’s development. Instead, it frames his work as a crucial chapter that builds upon the foundations laid by luminaries such as Archimedes, Bonaventura Cavalieri, Johannes Kepler, and John Wallis.

This pattern of building upon the work of predecessors is evident in Newton’s other intellectual pursuits. Drawing extensively from the writings of scholars like Descartes, Kepler, Galileo, and Ibn al-Haytham, he refined, adapted, and expanded upon the ideas put forth by earlier mathematicians and philosophers.

Many of these adaptations ultimately evolved into scientific revolutions. Newton’s groundbreaking concept of universal gravitation—regardless of whether its inspiration was a falling apple—had profound implications extending far beyond the realm of physics. His investigations into the properties of light, for instance, metaphorically illuminated the world with new understanding.

Those pivotal years spent in seclusion, away from the then-desolate academic halls of Cambridge, undoubtedly played a crucial role in establishing the groundwork for his subsequent decades of groundbreaking research.

So, what is the perceived inaccuracy? If Newton was demonstrably productive in 1666, why might we not find inspiration in his achievements during our own periods of enforced solitude?

Should Isaac Newton serve as your inspiration to resolve the Hubble constant conundrum, conquer the twin prime conjecture, or devise a low-fat brownie that actually pleases the palate, all before midday, then all credit to you.

For Newton, his academic pursuits were not mere novel diversions to fill newfound leisure time; they represented a continuation of a lifelong passion that transcended a brief period of plague. This pursuit was facilitated by a degree of privilege, which included the availability of household staff to manage domestic responsibilities.

His engagement with the mathematical concepts that contributed to the protracted development of calculus stemmed from his frustration in deciphering an astrology text acquired at a local fair. Furthermore, the extensive array of subjects that would occupy his thoughts during that period had already been documented in his personal notes long before any rumors of plague surfaced.

“Newton was able to do what he did not because of where he happened to find himself during the plague but because of who he was – one of the handful of greatest mathematicians and natural philosophers of all time, who, for several years, was able to do almost nothing else with his time but think, reason, and calculate.”

The narratives we construct around scientific discovery serve not only as commemorations of the past but also as paradigms that shape our approach to research in the present and future. We strive to meet these elevated standards and experience a sense of disappointment when we fall short of them.

While adversity can indeed present opportunities, there is no compelling reason to suggest that Newton’s period of confinement bore any resemblance to the isolation many of us are currently experiencing in 2020.

His narrative merits dissemination not as an isolated pivotal moment during a somber historical juncture, but rather as an integral link in a continuous chain of intellectual progress. This chain continues to flourish today, propelled by the unwavering dedication of every scientist, engineer, and thinker. This dedication persists, even in the absence of extraordinary, ‘miraculous’ years.