The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the United States Department of Energy have renewed their collaborative endeavor focused on the creation of a nuclear fission reactor intended for deployment on the lunar surface.

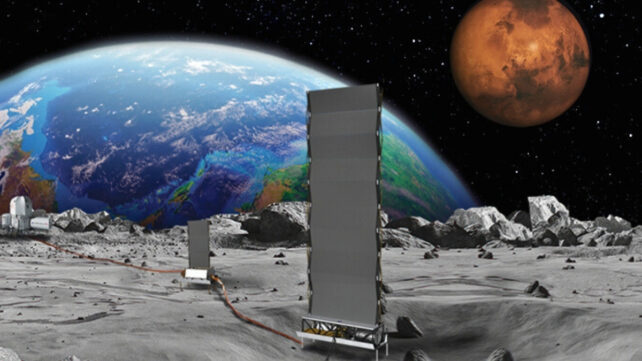

As detailed in a recent communication from the space agency, these two entities aim to conclude the developmental stages, which are anticipated to include terrestrial testing, of this groundbreaking facility by the year 2030. The intended function of this reactor is to deliver a consistent and sustained power supply for extended durations, facilitating future lunar surface expeditions and obviating the necessity for frequent propellant replenishment from Earth.

“This accord,” stated NASA administrator Jared Isaacman, “facilitates enhanced synergy between NASA and the Department of Energy, thereby furnishing the essential capabilities for advancing an era of profound space exploration and discovery.”

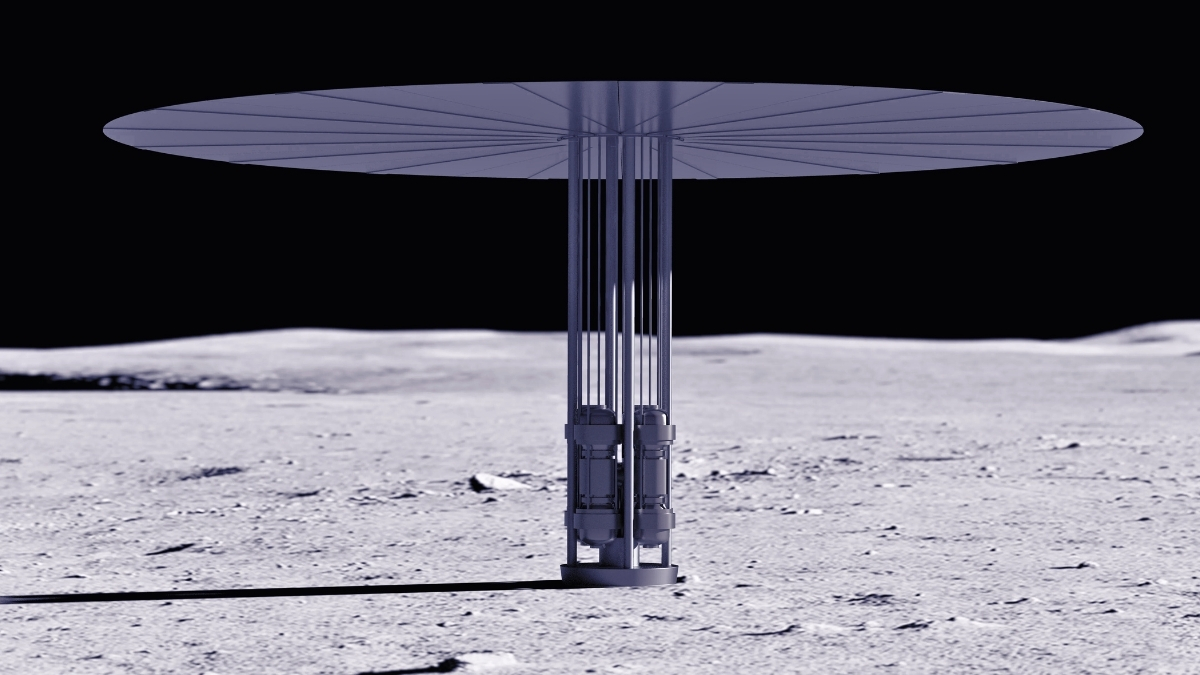

The undertaking is indeed formidable. Constructing a nuclear reactor that upholds stringent safety and reliability standards on Earth is inherently challenging. The Moon, however, presents a vastly different set of operational parameters, posing significant obstacles to the design of fission reactors. Paramount among these challenges is effectively managing waste heat.

On our planet, reactor cooling systems typically leverage water, which dissipates surplus thermal energy by transforming into steam that is then dispersed by the atmosphere. Conversely, fluid dynamics are substantially altered in environments with reduced gravity and minimal atmospheric pressure; the Moon is essentially a vacuum, lacking any substantial atmospheric circulation to aid in heat dissipation.

Potential mitigation strategies encompass the utilization of solid-state thermal conduction and liquid metal cooling agents, though each of these approaches introduces further design intricacies.

Furthermore, the lunar surface is perpetually covered in regolith. While it does not experience the scouring, planet-wide dust storms characteristic of Mars, lunar dust is both abrasive and electrostatically charged due to solar radiation. This fine particulate matter adheres tenaciously to surfaces, necessitating meticulous engineering for any equipment intended for lunar operations to prevent contamination and operational failures.

Beyond thermal management and dust mitigation, the reactor must incorporate robust radiation shielding to safeguard any astronauts operating in its vicinity. Moreover, the entire system must be engineered for exceptional durability to minimize the need for any on-site maintenance or repairs.

Technical solutions for these complex issues have been under investigation for an extended period, indicating that NASA and the DOE are building upon existing foundational research rather than commencing from scratch.

Current projections envision the design and development of a reactor capable of generating a minimum of 40 kilowatts of electrical power, a quantum sufficient for powering approximately 30 average-sized residences continuously for a decade. However, there is as yet no definitive deployment schedule for such a system on the Moon.

The initial design phase has indeed been successfully concluded. Nevertheless, the transformation of this conceptual design into flight-ready hardware is, by its very nature, a protracted endeavor, influenced as much by budgetary constraints and regulatory frameworks as by engineering advancements.

The implementation of a fission reactor on the Moon would represent an extraordinary asset for advancing space exploration. This recent announcement, however, suggests that this remains a long-term aspiration as opposed to an immediate prospect.