A recent scholarly examination of the world’s most ancient known botanical artistry, originating from the Halafian culture in northern Mesopotamia approximately 6000 BCE, uncovers profound cultural transformations embedded within its seemingly unassuming designs.

The elaborately adorned pottery signifies an nascent appreciation for the aesthetic merit of flora, according to the study’s contributors. Furthermore, the meticulous enumeration observed in the depicted floral petals points to a surprisingly advanced level of mathematical conceptualization.

This is not to suggest a deficiency in cognitive capacity for numerical thought among our antecedents; rather, it stems from a lack of empirical evidence for inscribed numerical symbols until the advent of proto-cuneiform numerical notations, which emerged around 3300 to 3000 BCE from southern Mesopotamian locales, millennia later.

“These ceramic vessels represent the inaugural instance in human history where individuals deliberately chose to represent the botanical realm as a subject meriting artistic contemplation,” state archaeologists Yosef Garfinkel and Sarah Krulwich of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, as detailed in their research.

“This phenomenon signifies a cognitive evolution linked to settled village existence and an burgeoning consciousness of symmetry and aesthetic principles.”

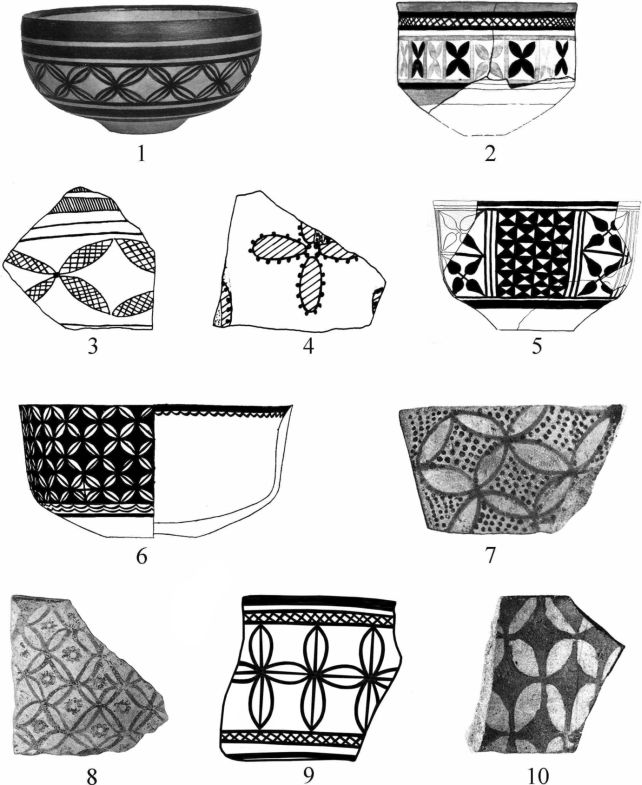

In their comprehensive inquiry, Garfinkel and Krulwich meticulously documented, juxtaposed, and scrutinized the plant-inspired designs adorning Halafian pottery sourced from 29 distinct archaeological excavation sites.

“The identification of artistic patterns necessitates a degree of interpretive discernment,” the research duo explicitly state.

“A considerable quantity of ceramic fragments presented herein as bearing [botanical] motifs were not recognized as such by the excavating archaeologists who initially published their findings.”

Garfinkel and Krulwich posit, based upon their investigative findings, that the flora rendered in the artwork – encompassing blossoms, saplings, arboreal specimens, branches, and stately trees – are unlikely to be associated with agricultural pursuits, given that they do not represent sustenance crops.

Conversely, the pair contend that this artistic expression may be rooted in a profound appreciation for botanical beauty and inherent symmetry, emerging from an early recognition of mathematical configurations.

“The capacity to partition space equitably, a feature evident in these floral representations, likely possessed utilitarian origins in the routines of daily existence, such as the apportionment of harvested goods or the designation of communal land tracts,” Garfinkel elaborates.

This proposition is corroborated by the stylistic rendition of the flora: their even distribution across the ceramic surfaces, the repetition of designs in rigid sequences, and, perhaps most remarkably, the precise count of petals adorning the floral motifs.

Numerous vessels, the investigators ascertained, exhibit one or more blossoms whose petals adhere to a geometric progression: 4, 8, 16, and 32. This intentional numerical sequence strongly suggests an underlying mathematical cognition. A few bowls even display 64 blossoms, maintaining this numerical pattern.

“These discernible patterns unequivocally demonstrate that the genesis of mathematical thought predates the advent of written language,” Krulwich asserts. “Individuals conceptualized divisions, sequences, and equilibrium through their creative endeavors.”