Dr. Hannah Long, a scientist affiliated with the University of Edinburgh, alongside her research associates, has elucidated how a specific segment of Neanderthal DNA demonstrates superior efficacy in stimulating a gene responsible for jaw formation compared to its modern human equivalent. This discovery offers a potential explanation for the more pronounced lower jaws observed in Neanderthals.

A representation of a Neanderthal. Image courtesy of the Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.

“The genetic blueprint of Neanderthals is remarkably akin to that of contemporary humans, with a mere 0.3% divergence. It is these subtle genetic distinctions that are presumed to be instrumental in shaping our differing physical characteristics,” remarked Dr. Hannah.

“Both human and Neanderthal genomes comprise approximately 3 billion nucleotide bases that encode proteins and govern gene expression within cells. Consequently, pinpointing genomic regions that influence physical traits is akin to locating a specific grain of sand on an expansive beach.”

Dr. Long and her collaborating authors harbored a reasoned hypothesis regarding the initial focus of their investigation: a particular genomic locus associated with Pierre Robin sequence, a congenital condition characterized by an underdeveloped lower jaw.

“In certain individuals afflicted with Pierre Robin sequence, this chromosomal area exhibits substantial DNA deletions or rearrangements. These alterations significantly impact facial development and constrain the growth of the jaw,” Dr. Hannah explained.

“We postulated that more minute variations within the DNA might exert less pronounced influences on the overall architecture of the face.”

Through a comparative analysis of human and Neanderthal genomes, the research team identified that within this specific region, measuring approximately 3,000 base pairs, only three single-nucleotide differences distinguished the two species.

Although this particular DNA segment does not directly encode proteins, it plays a regulatory role, dictating the timing and extent of gene activation. Specifically, it influences the expression of the SOX9 gene, a crucial orchestrator in the intricate process of facial development.

To substantiate the significance of these Neanderthal-specific genetic distinctions in facial morphogenesis, the scientists were compelled to demonstrate that the Neanderthal DNA segment could effectively trigger gene expression in the appropriate cellular populations at the precise developmental junctures during embryogenesis.

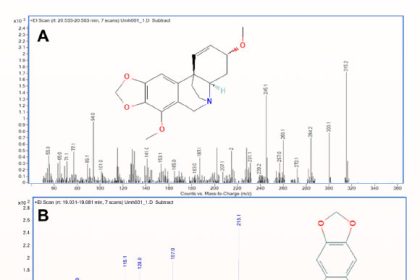

In a controlled experiment, they introduced both the Neanderthal and human versions of this regulatory region into the genome of zebrafish. Subsequently, the zebrafish cells were engineered to emit distinct fluorescent protein colors, contingent on whether the Neanderthal or human DNA segment was actively engaged in gene regulation.

Observing the developmental progression of the zebrafish embryos revealed that both the human and Neanderthal DNA segments were demonstrably active in the cellular lineages responsible for forming the lower jaw. Notably, the Neanderthal variant exhibited a higher level of transcriptional activity than its human counterpart.

“The initial observation of gene activation within specific cell populations adjacent to the developing jaw in the zebrafish embryos was profoundly exciting. This excitement was amplified by the discovery that the Neanderthal-specific genetic variations could modulate this developmental process,” Dr. Long conveyed.

“This pivotal finding prompted contemplation of the potential downstream consequences of these genetic differences and spurred ideas for their experimental exploration.”

Acknowledging the enhanced gene-activating capacity of the Neanderthal DNA sequence, the researchers then posited whether this resultant amplified activity of its target gene, SOX9, might consequently alter the morphology and functional characteristics of the adult jaw.

To rigorously test this hypothesis, the zebrafish embryos were supplemented with exogenous SOX9. The outcome indicated that the cellular components contributing to jaw formation occupied a demonstrably larger spatial area.

“Within our laboratory, we are committed to investigating the effects of additional DNA sequence variations by employing methodologies that recapitulate key aspects of facial development in vitro,” Dr. Long stated.

“We anticipate that these endeavors will enhance our comprehension of how sequence alterations contribute to the etiology of craniofacial conditions and thereby facilitate more precise diagnostic approaches.”

“This groundbreaking research underscores the profound insights that can be gleaned from studying extinct hominin species, illuminating our understanding of how our own genetic makeup drives facial variability, embryological development, and evolutionary trajectories.”

The findings of this study have been published in the esteemed scientific journal, Development.

_____

Kirsty Uttley et al. 2025. Neanderthal-derived variants increase SOX9 enhancer activity in craniofacial progenitors that shape jaw development. Development 152 (21): dev204779; doi: 10.1242/dev.204779