Available ethnohistoric records and contemporary archaeological insights indicate that Easter Island, also known as Rapa Nui, was characterized by a politically fragmented social structure, comprising numerous small, largely independent familial units dispersed throughout the territory. Consequently, the existence of over a thousand monumental statues, referred to as moai, provokes a fundamental inquiry: did the production activities at Rano Raraku, the principal quarry for these statues, operate under a centralized command, or did they mirror the fragmented organizational framework prevalent elsewhere on the island? By leveraging a dataset comprising more than 11,000 aerial images captured by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), archaeologists have now successfully generated the initial, comprehensive three-dimensional representation of the quarry, a tool designed to scrutinize these conflicting theoretical propositions.

The colossal moai statues of Easter Island stand as one of Polynesia’s most striking archaeological enigmas, with an aggregate of over 1,000 megalithic figures scattered across the petite volcanic isle, which spans a mere 163.6 square kilometers.

This substantial commitment of resources towards monument construction seems incongruous when juxtaposed with ethnohistoric narratives that consistently depict Rapa Nui society as organized into relatively diminutive, competing kin-based factions rather than a unified political entity.

Early ethnographic accounts documented a sociopolitical arrangement characterized by the presence of multiple distinct mata (clans or tribes) that maintained exclusive territorial demarcations, independent ceremonial sites, and autonomous leadership structures.

This historical context therefore precipitates the question of whether the creation of the moai was similarly organized in a non-centralized manner.

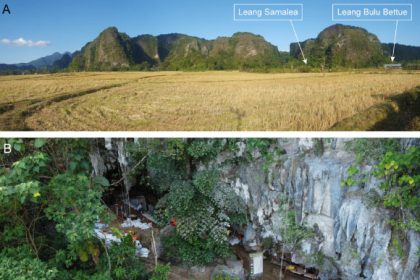

In a recently concluded investigation, Professor Carl Lipo of Binghamton University, in collaboration with his colleagues, amassed a collection of over 11,000 photographic images of Rano Raraku, the primary quarry for moai construction. These images were utilized to construct an exhaustive 3D model of the quarry, meticulously detailing hundreds of moai in various states of fabrication.

“From an archaeologist’s perspective, this quarry is akin to an archaeological wonderland,” stated Professor Lipo.

“It encapsulates virtually every conceivable aspect of moai construction, given that it served as the principal locus for the majority of their fabrication.”

“Historically, it has represented an immense reservoir of information and cultural heritage, yet it has remained remarkably underserviced in terms of detailed documentation.”

“The advancements in technology have been truly astonishing in their speed and scope,” commented Dr. Thomas Pingel from Binghamton University.

“The fidelity of this model far surpasses what would have been achievable even a short while ago, and the capacity to disseminate such an intricate representation in a format readily accessible from any standard computer is truly remarkable.”

An in-depth examination of the generated model revealed the presence of 30 distinct zones of quarrying activity, each exhibiting a variety of carving methodologies, thereby suggesting the existence of multiple autonomous work areas.

Furthermore, evidence indicates that moai were transported away from the quarry in numerous divergent directions.

These observable patterns lead to the conclusion that moai construction, much like the broader societal organization on Rapa Nui, was not dictated by a central administrative authority.

“We can discern separate workshops that demonstrably correspond to different kin groups, each diligently engaged within their specific delineated zones,” Professor Lipo explained.

“One can vividly observe from the construction patterns that a sequence of statues was being produced in one location, another array of statues in a different locale, and these were often positioned adjacent to one another. This clearly indicates the presence of distinct workshops.”

These discoveries challenge the widely held presumption that such a significant scale of monument production inherently necessitates a hierarchical organizational structure.

Any observed similarities among the moai appear to stem from the reciprocal exchange of information between cultural groups rather than from collaborative efforts on the part of communities to collectively sculpt the figures.

“A substantial portion of what is perceived as the ‘enigma of Rapa Nui’ arises from a deficit in readily accessible, detailed evidence that would empower researchers to rigorously evaluate proposed hypotheses and formulate comprehensive explanations,” the researchers elaborated.

“We are presenting the inaugural high-resolution three-dimensional model of the moai quarry at Rano Raraku, the primary source for nearly one thousand statues, thereby furnishing novel insights into the organizational and manufacturing processes involved in the creation of these monumental, megalithic effigies.”

The findings of this research were disseminated online on November 26, 2025, within the esteemed journal PLoS ONE.

_____

C.P. Lipo et al. 2025. Megalithic statue (moai) production on Rapa Nui (Easter Island, Chile). PLoS One 20 (11): e0336251; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0336251