A novel investigation suggests that humans possess a latent capacity for object detection sans direct interaction, a sensory faculty previously observed in certain animal species.

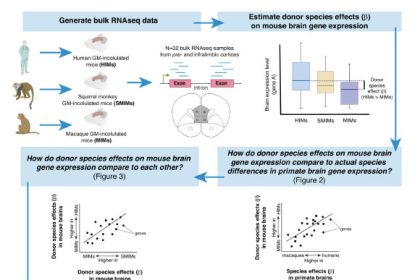

Chen et al. conducted a dual-faceted investigation, commencing with a human trial designed to evaluate fingertip acuity concerning tactile indicators from concealed items. The subsequent phase involved a robotic experiment employing a tactile-enabled robotic appendage and a Long Short-Term Memory model for subject identification. Image credit: Gemini AI.

The conventional understanding of human tactile perception posits it as a proximate sense, confined to engagements involving corporeal contact.

However, recent scientific discourse concerning animal sensory mechanisms has begun to interrogate this established paradigm.

Specifically, certain migratory birds, including sandpipers and plovers, have been documented to employ a form of remote tactile sensing to pinpoint subterranean prey within sandy substrates.

This modality of remote touch facilitates the detection of objects concealed beneath particulate matter by interpreting subtle mechanical vibrations propagated through the medium, particularly when adjacent dynamic pressures are introduced.

Within the scope of this recent research initiative, Dr. Elisabetta Versace, affiliated with Queen Mary University of London, alongside her research cohort, embarked on a mission to ascertain whether humans exhibit a comparable sensory aptitude.

Participants were instructed to gently maneuver their digits through sand in an effort to delineate the location of an unobtrusively positioned cube prior to direct physical engagement.

The experimental outcomes revealed a notable parallel in capability with that observed in shorebirds, a finding that is particularly striking given the absence of specialized cranial appendages in humans that confer this sense upon avian counterparts.

Through the modeling of the physical parameters governing this phenomenon, the researchers discerned that the human hand demonstrates an exceptional degree of sensitivity, capable of discerning the presence of buried articles by registering minute perturbations within the surrounding granular environment.

This level of sensitivity closely approximates the theoretical physical limit for detection based on mechanical ‘reflections’ within granular media; these reflections occur when sand displacement interacts with a stable surface, such as a submerged object.

When contrasting human performance with that of a robotic tactile sensor that had undergone training via a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) algorithm, humans achieved an impressive accuracy rate of 70.7% within the anticipated range of detectability.

Intriguingly, while the robotic system demonstrated a marginally superior capability in sensing objects from greater distances on average, it was prone to generating erroneous positive identifications, resulting in an overall precision score of only 40%.

These revelations serve to corroborate the assertion that individuals can indeed perceive an object’s presence prior to direct physical contact, a remarkable capacity for a sense typically associated with proximal engagements.

Both human participants and the robotic sensor exhibited performance levels closely aligned with the maximum sensitivity predicted by physical models of displacement.

The investigation elucidates the human capacity to detect objects embedded within sand before any direct physical engagement, thereby broadening our comprehension of the extended reach of the tactile sense.

It furnishes empirical evidence of a tactile proficiency that had not been previously documented in human subjects.

Furthermore, these findings offer valuable calibration points for the advancement of assistive technologies and robotic tactile perception systems.

By leveraging human perceptual capabilities as a foundational model, engineers are empowered to conceptualize robotic systems that integrate a naturalistic tactile sensitivity for practical applications, such as subsurface exploration, excavation, or reconnaissance missions where visual input is compromised.

“This marks the inaugural study of remote touch in human subjects, and it fundamentally alters our perspective on the perceptual capabilities, or ‘receptive fields,’ of living organisms, including humankind,” stated Dr. Versace.

“This discovery unlocks potential avenues for the creation of instruments and assistive devices that augment human tactile perception,” commented Zhengqi Chen, a doctoral candidate at Queen Mary University of London.

“These insights may inform the development of sophisticated robotic systems capable of performing delicate operations, for instance, the non-destructive retrieval of archaeological artifacts or the exploration of granular terrains such as extraterrestrial regolith or oceanic seabeds.”

“On a broader level, this research lays the groundwork for touch-enabled systems that enhance the safety, intelligence, and efficacy of exploring concealed or hazardous environments.”

“What renders this research particularly stimulating is the synergistic interplay between the human and robotic studies,” observed Dr. Lorenzo Jamone, a research fellow at University College London.

“The human experiments provided crucial direction for the robot’s learning algorithms, and conversely, the robot’s performance shed new light on the interpretation of the human data.”

“This exemplifies an outstanding instance of interdisciplinary synergy, demonstrating how psychology, robotics, and artificial intelligence can coalesce to foster both fundamental scientific breakthroughs and technological innovation.”

The research findings were formally presented in September at the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning (ICDL), held in Prague, Czech Republic.

_____

Z. Chen et al. Exploring Tactile Perception for Object Localization in Granular Media: A Human and Robotic Study. 2025 IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning; doi: 10.1109/ICDL63968.2025.11204359