The catastrophic event unfolded when the container vessel MV Dali, a colossal craft measuring 300 metres in length and weighing approximately 100,000 tonnes, experienced a loss of propulsion and collided with a crucial supporting pier of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore. This impact precipitated the swift structural failure and subsequent demise of the bridge. Tragically, six individuals are presumed lost, with several others sustaining injuries. The city and its environs are now confronted with the prospect of a protracted logistical quandary, spanning several months, due to the severance of this vital transportation artery.

This incident delivered a profound shock, resonating not only with the general populace but also with seasoned bridge engineers such as myself. Our professional endeavors are intensely focused on guaranteeing the integrity and safety of these structures. Statistically speaking, the likelihood of experiencing harm or a worse fate due to a bridge collapse remains considerably lower than the probability of being struck by lightning.

Nevertheless, the distressing imagery emanating from Baltimore serves as a potent reminder that safety cannot be presumed or taken for granted. A state of heightened vigilance is imperative.

Consequently, the pertinent questions arise: what factors led to this bridge’s failure? And, of equal significance, how can we enhance the resilience of other bridge structures against similar catastrophic events?

A 20th Century Structure Encounters a 21st Century Vessel

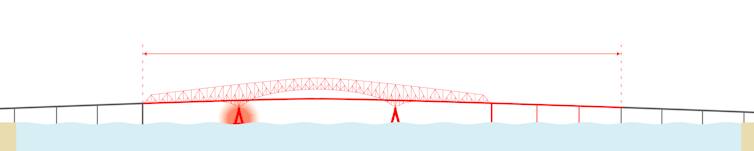

The Francis Scott Key Bridge, a monumental undertaking, was constructed throughout the mid-1970s and officially inaugurated in 1977. The primary segment spanning the navigable channel is characterised as a “continuous truss bridge,” comprising three distinct sections or spans.

The edifice is supported by four substantial piers, with two situated on either side of the main waterway. These two specific piers are of paramount importance for safeguarding against maritime impacts.

Indeed, the bridge was outfitted with a dual-layered protective system: a robust “dolphin” structure constructed from concrete, and an additional fender. The dolphins are strategically positioned in the water, approximately 100 metres upstream and downstream from the piers. Their intended function is to act as sacrificial elements in the event of a misdirected vessel, absorbing the kinetic energy of impact and deforming in the process, thereby shielding the bridge structure itself from direct contact.

The fender represents the final tier of defence. This component is engineered from timber and reinforced concrete, encircling the principal bridge piers. Its design objective is to dissipate the energy generated by any potential impact.

However, fenders are fundamentally not engineered to withstand the forces associated with impacts from exceptionally large vessels. Consequently, when the MV Dali, a vessel exceeding 100,000 tonnes in displacement, circumvented the protective dolphins, its sheer mass rendered it far too formidable for the fender system to effectively counteract.

Video evidence reveals a cloud of particulate matter emerging just prior to the bridge’s collapse, which is strongly suggestive of the fender system’s disintegration as it was overwhelmed by the immense force of the ship.

Once the colossal vessel had successfully penetrated both the dolphin structure and the fender, the pier—one of the bridge’s four primary load-bearing supports—was simply unable to resist the resultant impact. Taking into account the vessel’s considerable dimensions and its approximate velocity of 8 knots (equivalent to 15 kilometres per hour), the calculated force of the impact would have been in the vicinity of 20,000 tonnes.

Progress in Bridge Safety Enhancements

This unfortunate occurrence was not the inaugural instance of a vessel striking the Francis Scott Bridge. A prior collision transpired in 1980, inflicting such substantial damage to a fender that its complete replacement became necessary.

Globally, a review of data from 1960 to 2015 indicates that approximately 35 significant bridge collapses resulting in fatalities were attributed to vessel collisions, according to a 2018 report compiled by the World Association for Waterborne Transport Infrastructure. The period encompassing the 1970s and early 1980s witnessed a series of ship-bridge collisions that served as catalysts for substantial advancements in the design methodologies aimed at fortifying bridges against impact.

Subsequent impact events during the 1970s and early 1980s were instrumental in driving considerable refinements to the design regulations governing impact resilience.

Key publications that redefined bridge design standards include the International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering’s Ship Collision with Bridges guide, released in 1993, and the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials’ Guide Specification and Commentary for Vessel Collision Design of Highway Bridges (1991).

In Australia, the Australian Standard for Bridge Design, updated in 2017, mandates that designers meticulously assess the largest vessel anticipated within the subsequent century and project the consequences of a full-speed collision with any bridge pier. This assessment encompasses the potential outcomes of both direct, head-on impacts and glancing side-on collisions. A direct consequence of these stringent requirements is that many contemporary bridges feature their piers fortified by entirely artificial island-like structures.

It is important to acknowledge that these critical design enhancements were implemented subsequent to the original construction of the Francis Scott Key Bridge, and thus did not influence its initial design parameters.

Inferences Drawn from Calamity

At this nascent stage of analysis, several key lessons emerge.

Firstly, it is unequivocally evident that the protective measures implemented for this particular bridge proved insufficient to mitigate the impact of the vessel. Contemporary cargo vessels are considerably larger than their counterparts from the 1970s, suggesting that the Francis Scott Key Bridge was likely not engineered with a collision of this magnitude in contemplation.

Therefore, a primary takeaway is the imperative to continuously evaluate and comprehend the evolving characteristics of maritime traffic operating in proximity to our bridges. This necessitates a departure from complacency; we must ensure that the protective systems surrounding our bridges are dynamically adapted and enhanced in tandem with the advancements in vessel technology.

Secondly, and on a broader spectrum, a steadfast commitment to diligent bridge management is paramount. I have previously articulated my perspectives on the current safety status of Australian bridges, alongside potential avenues for improvement.

This profoundly tragic incident underscores with stark clarity the critical need for increased investment in the maintenance of our aging infrastructure. This sustained commitment is the sole reliable pathway to ensuring that these vital assets remain safe and fully functional, capable of meeting the ever-increasing demands placed upon them in the modern era.

Colin Caprani, Associate Professor, Civil Engineering, Monash University