Vehicles for passenger use in Australia are generating 50% more carbon dioxide (CO₂) than the global average observed across major international markets. Furthermore, the actual on-road performance reveals a more concerning reality than what official statistics indicate.

This revelation stems from a recent investigation that scrutinised the CO₂ emission output of cars, SUVs, and light commercial vehicles within Australia in comparison to their international counterparts.

The comparative analysis suggests that Australia is highly likely to fall significantly short of its 2050 economy-wide net-zero emission objective pertaining to road transport. To achieve this target, a substantial intensification of policies aimed at reducing vehicle emissions is imperative, coupled with support from a comprehensive suite of complementary policies.

This month, the Australian government unveiled several prospective options for a New Vehicle Efficiency Standard (NVES). It is important not to confuse this initiative with the National Electric Vehicle Strategy (NEVS). Each proposed option would establish a national benchmark for the maximum CO₂ emissions permitted per kilometre driven, calculated as an average across all new vehicles sold.

Globally, mandatory CO₂ emission or fuel-efficiency standards are acknowledged as a cornerstone for curtailing transport-related emissions.

To provide additional context and contribute to the development of Australia’s forthcoming standard, the Australian entity Transport Energy/Emission Research (TER), in conjunction with the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), undertook a collaborative effort resulting in a recently published briefing document.

The independent assessment highlights the critical necessity for Australia to implement a rigorous, thoughtfully designed, and compulsory fuel-efficiency standard. Such a standard, along with supplementary policy measures, is indispensable for keeping pace with technological advancements and the decarbonisation efforts underway in other developed nations.

What Factors Led to This Disparity?

Both fuel efficiency and emission standards pursue a largely identical objective: the reduction of fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Concurrently, these measures result in decreased fuel expenses for consumers and enhanced energy security.

Approximately 85% of the global market for light vehicles has progressively adopted these standards, with some nations implementing them decades ago. Countries such as the United States, European Union member states, Canada, the United Kingdom, Japan, China, South Korea, Brazil, Mexico, New Zealand, Chile, and India all have such regulations in place. Australia and Russia stand as the sole exceptions among developed economies.

Australia has a protracted history of discussions surrounding the mandatory implementation of these standards for passenger and light commercial vehicles. The federal government has issued no fewer than six public consultation documents since 2008, yet mandatory standards have not been established. However, this situation is poised for a change.

Voluntary standards have been in effect in Australia since 1978. These benchmarks have not consistently been met due to a deficiency in enforcement mechanisms. Furthermore, they have drawn criticism for a lack of both ambition and efficacy in achieving actual reductions in real-world emissions.

It would appear that the government’s present proposition is set to be more ambitious. It potentially aims to align with US targets by 2027, though it may not reach the level of stringency observed in Europe. The ultimate effectiveness of the Australian standard in securing tangible emission reductions and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 will require careful evaluation once the detailed design and specifics become clearer.

How Does Australia’s Performance Stack Up Based on Official Data?

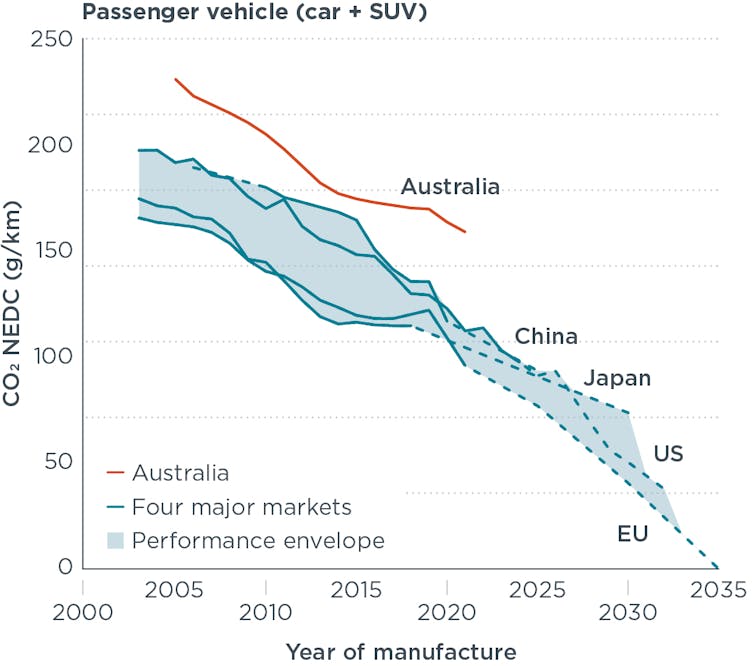

The newly released study conducted a comparative analysis of the officially reported CO₂ emission performance of passenger and light commercial vehicles in Australia against data from China, the EU, Japan, and the US. Our findings indicate that CO₂ emissions from Australian passenger vehicles were 53% higher than the average recorded by these major international markets in 2021.

(TER and ICCT, 2024)

Crucially, without the implementation of effective measures, this performance deficit is projected to widen in the coming years. This is a direct consequence of these other leading markets aggressively adopting standards that accelerate the transition towards a vehicle fleet with low or zero emissions.

How Does Australia’s Reality Compare?

The official Australian figures are derived from a testing methodology known as the New European Drive Cycle (NEDC). This protocol was initially developed in the early 1970s.

The primary issue lies in the fact that the disparity between NEDC test results and actual on-road emissions has steadily escalated. Estimates indicate that actual on-road emissions were approximately 10% higher in 2007, a figure that grew to over 45% by 2021.

Indeed, the European Union has long since moved beyond the antiquated NEDC protocol. It has adopted a more representative testing procedure, known as the Worldwide Harmonised Light-Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP).

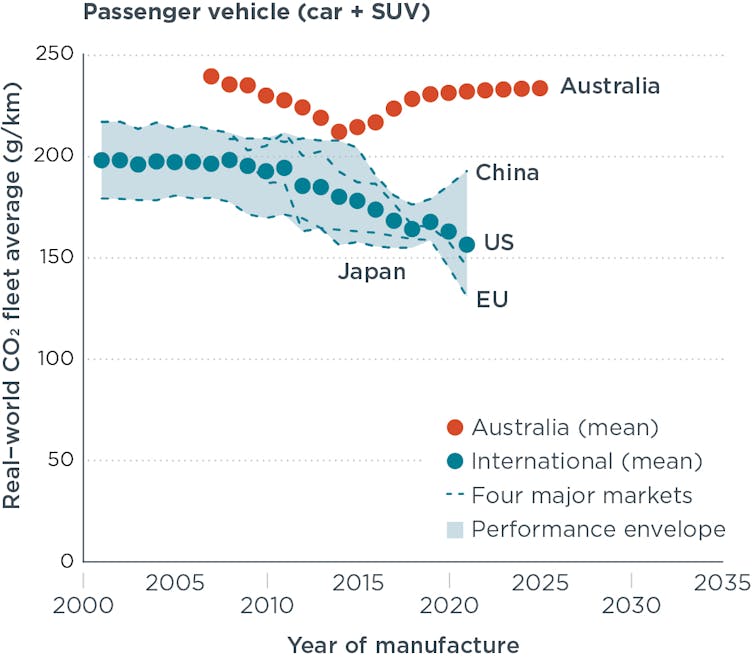

The briefing paper incorporated prior research into Australian and international real-world emission performance to construct a more precise comparison. While the official data suggests that newly sold Australian passenger vehicles exhibit relatively elevated emissions, these figures, at least nominally, appear to have improved annually. The scenario changes considerably when examining on-road emissions.

(TER and ICCT 2024)

Our estimations suggest that emissions from newly purchased Australian passenger vehicles have actually been on an upward trajectory since 2015. This trend can be attributed to the increasing dimensions and weight of vehicles, a shift towards more four-wheel-drive SUVs and large utility vehicles, and the absence of mandatory standards or specific targets.

Australia’s real-world emission performance also demonstrates a significantly poorer standing compared to the four major markets. Prior to 2016, the average difference saw Australian emissions being approximately 20% higher. By 2021, this figure had escalated, with passenger vehicles in Australia emitting almost 50% more.

Policy Implications of These Findings

Our analysis unequivocally demonstrates that both officially reported and actual on-road CO₂ emissions from Australia’s new light-duty vehicles substantially exceed those in other developed nations. The available evidence strongly suggests that this subpar performance will exacerbate without the implementation of stringent, mandatory standards.

Encouragingly, governmental action is being taken to address the deficiency in effective standards. It is anticipated that mandatory standards will be enacted this year. The New Vehicle Efficiency Standard is scheduled to come into effect in 2025.

Nevertheless, the utmost care must be exercised in designing this standard to ensure it facilitates genuine emission reductions for newly manufactured vehicles.

For instance, the official Australian testing protocol (NEDC) is antiquated and increasingly fails to accurately reflect on-road emissions. It presents a distorted and unrealistic perspective, thereby impeding effective emission reduction efforts. The government has indicated its intention to adopt a more accurate testing protocol.

Furthermore, the standards ought to incorporate onboard monitoring of fuel consumption, a practice currently being implemented by the EU. It is paramount to accurately measure the real-world fuel efficiency and emissions of new vehicles and to disseminate this information publicly to verify that the standards are achieving their intended objectives. However, the most recent government report did not reference this crucial aspect.

The introduction of a mandatory fuel-efficiency standard is long overdue in Australia. Such a standard holds the potential to bridge the performance gap between Australia and the global community. Consequently, it is imperative that we ensure its efficacy.

![]()