Contrary to what might be expected, ice at a frigid minus 10 degrees Celsius facilitates the release of significantly more iron from prevalent mineral types compared to liquid water maintained at 4 degrees Celsius. This groundbreaking revelation, stemming from the collaborative efforts of researchers at Umeå University, the Institut des Sciences Chimiques de Rennes, and CNRS, offers a compelling explanation for the increasingly observed phenomenon of Arctic rivers exhibiting a rusty orange hue as permafrost undergoes thawing in our warming global climate.

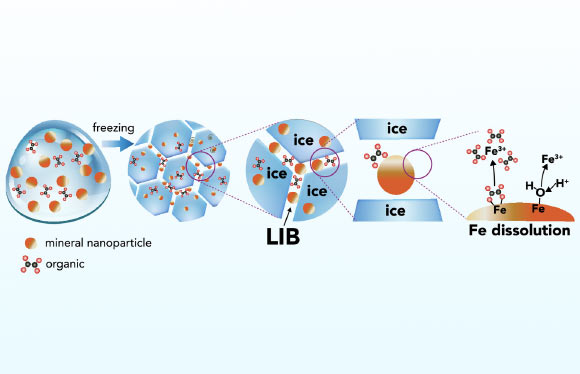

Schematic representation of iron mineral dissolution reactions in ice. Image credit: Sebaaly et al., doi: 10.1073/pnas.2507588122.

Expressing surprise at the implications, Professor Jean-François Boily of Umeå University stated, “While it may seem counterintuitive, ice is far from being a mere inert frozen mass.”

“The process of freezing actively generates minute pockets of unfrozen liquid water interspersed among the ice crystals.”

“These micro-environments function as miniature chemical reactors, where dissolved substances become highly concentrated and develop extreme acidity.”

“Consequently, these conditions enable reactions with iron-bearing minerals even at temperatures as low as minus 30 degrees Celsius.”

To meticulously investigate this phenomenon, Professor Boily and his associates conducted a study focusing on goethite, a mineral composed of iron oxide that is widely distributed, in conjunction with an organically derived acid found naturally.

Through the application of sophisticated microscopy techniques and empirical experimentation, they ascertained that repeated cycles of freezing and thawing significantly enhance the efficiency of iron dissolution.

As the ice undergoes successive freezing and melting events, organic constituents previously encapsulated within the ice are liberated, thereby catalyzing further chemical transformations.

Furthermore, the concentration of dissolved salts, or salinity, emerges as a critical factor; freshwater and brackish water conditions promote increased dissolution of iron, while saltwater environments tend to inhibit this process substantially.

These groundbreaking findings are particularly relevant to environments characterized by acidity, such as sites impacted by acid mine drainage, atmospheric dust that has frozen, acid sulfate soils found along the Baltic Sea coastline, or indeed any frozen locale with acidic conditions where iron minerals are in contact with organic matter.

“With the ongoing progression of global climate warming, the frequency of freeze-thaw cycles is steadily increasing,” observed Angelo Pio Sebaaly, a doctoral candidate at Umeå University.

“Each of these cycles facilitates the release of iron from terrestrial soils and permafrost into adjacent water bodies. This process has the potential to adversely impact water quality and disrupt aquatic ecosystems across extensive geographical areas.”

“The outcomes of this research underscore that ice should not be regarded as a simple passive reservoir, but rather as an active participant in chemical processes.”

“As the phenomenon of freezing and thawing intensifies in polar and mountainous regions, the ramifications for ecological systems and the fundamental biogeochemical cycling of elements could prove to be substantial.”

The comprehensive study authored by this research team was officially published on August 26, 2025, in the esteemed journal, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____