The groundbreaking distributed computing initiative SETI@home, established in 1999, empowered countless volunteers globally to scrutinize radio signals originating from the cosmos. This extensive endeavor yielded approximately 12 billion distinct signals—transient energy pulses that stood out against ambient radio noise—derived from data collected at the now-decommissioned Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Recently, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley have meticulously refined this vast dataset, isolating about 100 intriguing signals that warrant further investigation using high-performance radio telescopes.

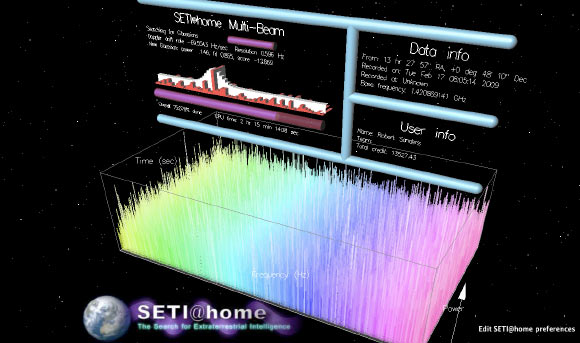

A screenshot of the SETI@home user interface on a desktop computer in 2009. Image credit: Robert Sanders / UC Berkeley.

From 1999 through 2020, a vast international community contributed their personal computers to the SETI@home project, aiding the search for evidence of advanced extraterrestrial civilizations within our Milky Way Galaxy.

Participants downloaded and executed the SETI@home software, enabling their machines to process observational data gathered by the Arecibo Observatory in the quest to identify anomalous radio transmissions from space.

In aggregate, these collective computational efforts registered 12 billion unique signal detections.

Following a decade of dedicated analysis, the SETI@home team has concluded its examination of these detections, progressively narrowing the field from an initial million candidate signals down to precisely 100 that merit more rigorous scrutiny.

“SETI@home represents a radio-based Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence project, designed to detect various types of signals within archived astronomical data,” explained Dr. David Anderson, a computer scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, and a co-founder of the SETI@home initiative.

“The preponderance of this collected data was acquired concurrently during observations at the Arecibo Observatory over a span of 22 years.”

“Additional data contributions were received from the Parkes and Green Bank observatories, as part of the Breakthrough Listen initiative.”

“Most radio SETI investigations involve processing observational data in near real-time, utilizing specialized analytical instruments at the telescope facility.”

“SETI@home adopts a distinct methodology: it archives digital time-domain (also referred to as baseband) data, subsequently disseminating it across the internet to a large distributed network of computers that conduct the data processing, leveraging both central processing units (CPUs) and graphics processing units (GPUs).”

The most promising SETI@home signals are presently undergoing re-examination by China’s Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST), with the objective of determining if any exhibit recurring patterns or characteristics inconsistent with natural cosmic noise.

“I harbor no expectation of discovering a definitive extraterrestrial signal,” Dr. Anderson stated.

“Were a signal of a certain power threshold to exist, we would have already identified it.”

The multistep analytical framework employed by SETI@home, as detailed in two scholarly articles published in the Astronomical Journal, serves as both a methodological blueprint and a valuable cautionary account for future endeavors in the search for technosignatures.

The inaugural publication elucidated the process by which the project’s distributed network of personal computers applied sophisticated signal processing techniques to raw time-domain radio data. This involved methodologies such as discrete Fourier transforms to detect spectral signatures that could indicate a persistent extraterrestrial transmission source.

A subsequent article addressed the intricate challenge of differentiating potential signals from the pervasive background noise generated by terrestrial sources—including satellites, broadcast transmissions, and even domestic microwave ovens. This was achieved by identifying clusters of detections that consistently originated from a single point in the sky across multiple observation periods.

Future research initiatives could build upon the SETI@home paradigm by distributing new astronomical datasets through platforms such as BOINC—the volunteer computing infrastructure that SETI@home was instrumental in developing—thereby re-engaging public processing power. This would be facilitated by more advanced analytical tools and enhanced network capabilities.

“The allure of searching for intelligent extraterrestrial life continues to capture the public imagination,” remarked Dr. Eric Korpela, director of the SETI@home project and an astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley.

“I believe it remains feasible to harness significantly more processing power than was utilized for SETI@home and to analyze a greater volume of data, owing to the proliferation of wider internet bandwidth.”

“The primary obstacle for such an undertaking lies in the requirement for dedicated personnel, which translates directly into salary expenses. Consequently, this is not the most cost-effective approach to SETI research.”

_____

David P. Anderson et al. 2025. SETI@home: Data Analysis and Findings. AJ 170, 111; doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/ade5ab

E.J. Korpela et al. 2025. SETI@home: Data Acquisition and Front-end Processing. AJ 170, 112; doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/ade5a7