A substantial collection of dugong skeletal remains has been excavated at the Al Maszhabiya locality, situated within Qatar’s Early Miocene Dam Formation. This paleontological discovery indicates that the Arabian Gulf has historically supported diverse sea cow communities, featuring distinct species over the last 20 million years. Notably, one of these extinct species has been identified and named Salwasiren qatarensis, representing a novel scientific classification.

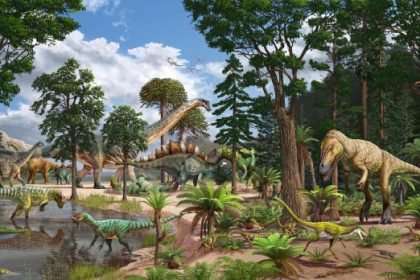

An artistic reconstruction of a herd of Salwasiren qatarensis foraging on the seafloor. Image credit: Alex Boersma.

With their robust physique and distinctive downturned snouts adorned with sensitive vibrissae, modern-day dugongs (Dugong dugon) bear a striking resemblance to their manatee relatives.

The primary anatomical distinction between these purely herbivorous marine mammals, commonly referred to as sea cows, lies in their caudal appendages: while manatees possess a rounded, paddle-like tail, dugongs are characterized by a fluked tail reminiscent of a dolphin’s.

Dugongs are indigenous to the coastal waters spanning from Western Africa, through the Indo-Pacific region, and extending to Northern Australia.

The Arabian Gulf is currently home to the world’s most populous dugong aggregation, where these marine mammals function as crucial ecosystem engineers.

Through their grazing on seagrass, dugongs actively modify the seabed, creating feeding channels that liberate sequestered nutrients into the surrounding aquatic environment, thereby benefiting other marine flora and fauna.

“We have identified a progenitor of dugongs within geological strata located less than 16 kilometers (10 miles) from a bay characterized by seagrass meadows, which constitute their primary contemporary habitat,” stated Dr. Nicholas Pyenson, the curator of fossil marine mammals at the National Museum of Natural History.

“This geographical area has served as a preeminent habitat for sea cows for the past 21 million years; it is simply that the ecological niche has been occupied by a succession of different species throughout this extensive period.”

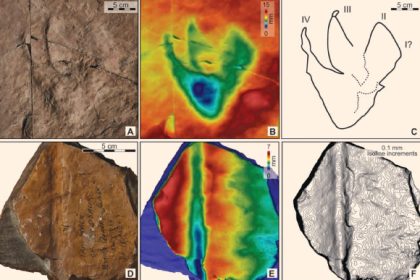

Few locations exhibit such an extensive preservation of these ossified remnants as Al Maszhabiya, a significant paleontological site situated in southwestern Qatar.

The bonebed was initially brought to light during geological surveys conducted for mining and petroleum exploration in the 1970s, when numerous ‘reptilian’ bones were observed strewn across the desert landscape.

In the early 2000s, paleontologists revisited the site and promptly discerned that the unearthed fossils were not attributable to ancient reptiles but rather to extinct sea cows.

Based on the surrounding geological formations, Dr. Pyenson and his research collaborators have dated the bonebed to the Early Miocene epoch, approximately 21 million years ago.

Their excavations revealed fossil evidence indicating that this region was formerly a shallow marine ecosystem frequented by sharks, barracuda-like piscine species, prehistoric cetaceans, and marine chelonians.

More than 170 distinct locations containing fossilized sea cow remains were cataloged across the Al Maszhabiya site.

This discovery positions the bonebed as the most prolific accumulation of fossilized sirenia bones globally.

The preserved skeletal structures at Al Maszhabiya bore resemblances to the osteology of extant dugongs. However, these ancient aquatic herbivores still possessed rudimentary hind limb bones, a feature that modern dugongs and manatees have lost through evolutionary processes.

Furthermore, the prehistoric sea cows from this locale exhibited a straighter rostral profile and less developed tusks compared to their contemporary counterparts.

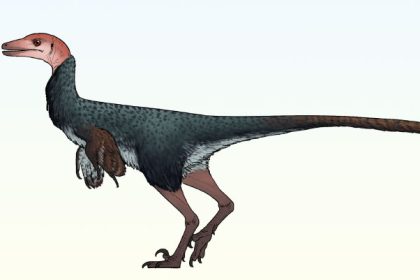

The scientific team has officially categorized the fossil sea cows discovered at Al Maszhabiya as a new species, designated as Salwasiren qatarensis.

“It seemed entirely appropriate to incorporate the nation’s appellation into the species’ designation, as it unequivocally signifies the provenance of the fossil discoveries,” remarked Dr. Ferhan Sakal, a researcher affiliated with Qatar Museums.

With an estimated body mass of 113 kilograms (250 pounds), Salwasiren qatarensis would have weighed comparably to an adult terrestrial panda or a heavyweight boxing champion.

Nevertheless, it ranked among the smaller species of sea cows ever documented. Certain extant dugong species can attain weights nearly eight times that of Salwasiren qatarensis.

Based on the fossil evidence, the researchers propose that this region was abundant with seagrass beds over 20 million years ago, during a geological epoch when the Gulf constituted a biological hotspot of considerable diversity. Sea cows were instrumental in tending to these underwater meadows.

“The exceptional density of the Al Maszhabiya bonebed strongly suggests that Salwasiren qatarensis fulfilled the role of a seagrass ecosystem engineer during the Early Miocene, mirroring the functional importance of dugongs in contemporary marine environments,” Dr. Pyenson elucidated.

“There has been a complete substitution of the evolutionary lineages involved, but their ecological functions have remained remarkably consistent.”

The findings of this research endeavor are comprehensively detailed in a scholarly publication made available online in the scientific journal PeerJ.

_____

N.D. Pyenson et al. 2025. High abundance of Early Miocene sea cows from Qatar shows repeated evolution of seagrass ecosystem engineers in Eastern Tethys. PeerJ 13: e20030; doi: 10.7717/peerj.20030