The world’s largest island, Greenland, boasts some of the planet’s most substantial natural resource endowments.

These encompass vital raw materials, including lithium and rare earth elements (REEs), which are fundamental to green technologies. However, their extraction and sustainability are subjects of considerable sensitivity. Furthermore, Greenland possesses other valuable minerals, metals, and vast reserves of hydrocarbons, such as oil and natural gas.

Beneath the ice lie three REE-bearing deposits in Greenland that may rank among the largest globally by volume. These reserves represent significant potential for manufacturing the batteries and electronic components indispensable to the worldwide energy transition.

The sheer magnitude of Greenland’s hydrocarbon potential and mineral wealth has spurred extensive investigations by Denmark and the United States into the economic and environmental feasibility of novel ventures like mining.

According to estimates from the US Geological Survey, the onshore region of northeast Greenland, encompassing ice-covered areas, is believed to contain approximately 31 billion barrels of oil-equivalent in hydrocarbons. This figure is comparable to the total proven crude oil reserves of the entire United States.

However, Greenland’s ice-free landmass, an area nearly twice the size of the United Kingdom, constitutes less than one-fifth of the island’s total surface. This disparity suggests the potential presence of extensive, as-yet-unexplored natural resources concealed beneath the glacial ice.

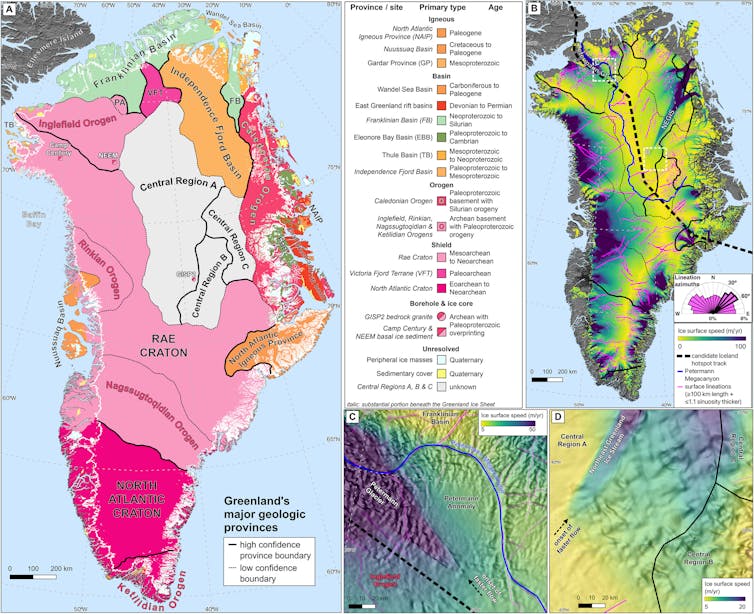

Greenland’s abundant natural resource wealth can be attributed to its remarkably diverse geological history spanning the last 4 billion years. The island hosts some of the Earth’s most ancient rock formations, alongside massive, truck-sized deposits of native iron (not of meteoritic origin).

Diamond-bearing kimberlite “pipes” were identified in the 1970s but have not yet been commercially exploited, primarily due to the significant logistical hurdles associated with their extraction. These occurrences were notably discovered in the 1970s.

From a geological perspective, it is exceptionally rare and of great interest to geologists that a single region has undergone all three primary geological processes responsible for the formation of natural resources, ranging from hydrocarbons and REEs to precious gemstones. These processes are linked to distinct geological events such as mountain formation, crustal extension (rifting), and volcanic activity.

Greenland’s landscape has been profoundly shaped by numerous extended periods of orogeny (mountain building). The immense compressional forces involved fractured the Earth’s crust, facilitating the deposition of valuable minerals like gold, rubies, and graphite within fault lines and fissures.

Graphite is an essential component for the manufacture of lithium-ion batteries. However, its potential in Greenland remains largely “underexplored,” according to the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, especially when contrasted with major global producers like China and South Korea.

The most substantial portion of Greenland’s natural resource endowment, however, originates from its epochs of rifting. This includes the geologically recent formation of the Atlantic Ocean, which commenced at the dawn of the Jurassic Period, just over 200 million years ago.

Greenland’s onshore sedimentary basins, such as the Jameson Land Basin, appear to hold considerable promise for oil and gas reserves, mirroring the hydrocarbon-rich continental shelf of Norway.

Nevertheless, prohibitive extraction costs have significantly constrained commercial exploration efforts. Furthermore, a burgeoning body of research indicates the potential for extensive petroleum systems encircling the entirety of offshore Greenland.

Metals including lead, copper, iron, and zinc are also present within the onshore sedimentary basins (which are predominantly ice-free). These have been extracted locally on a small scale since as early as 1780, according to historical geological records.

Challenging-to-Acquire Rare Earth Elements

While not as directly linked to volcanic phenomena as neighboring Iceland—a unique location situated at the confluence of a mid-ocean ridge and a mantle plume—many of Greenland’s critical raw materials owe their existence to its volcanic past.

Rare earth elements such as niobium, tantalum, and ytterbium have been detected in igneous rock strata. This mirrors the discovery and subsequent mining of silver and zinc deposits in south-west England, which were formed by the circulation of hot hydrothermal fluids at the fringes of substantial volcanic intrusions.

Critically among the REEs, Greenland is projected to hold substantial sub-ice reserves of dysprosium and neodymium. These reserves could potentially meet more than a quarter of projected global demand, totaling nearly 40 million tonnes.

These specific elements are increasingly recognized as the most economically significant yet challenging REEs to source. Their indispensable roles in wind power generation, electric vehicle motors for sustainable transport, and high-temperature magnets used in applications like nuclear reactors underscore their importance.

The development of known REE deposits, such as Kvanefield in southern Greenland, and potentially undiscovered ones in the island’s central rocky interior, could exert considerable influence on the global REE market due to their relative scarcity worldwide.

A Confounding Predicament

The global energy transition has been spurred by a growing public awareness of the extensive dangers posed by the combustion of fossil fuels. However, climate change presents significant implications for the accessibility of many of Greenland’s natural resources that are presently buried beneath vast ice sheets—resources that are integral to this very energy transition.

An area equivalent in size to Albania has experienced melting since 1995, a trend anticipated to intensify unless global carbon emissions are drastically reduced in the immediate future.

Advanced survey methodologies, including the application of ground-penetrating radar, now enable us to visualize the sub-ice environment with enhanced accuracy. We can now ascertain the precise bedrock topography beneath up to 2 kilometers of ice cover, providing invaluable insights into Greenland’s subsurface mineral potential.

Nevertheless, progress in prospecting beneath the ice remains slow, and the challenges associated with sustainable extraction are likely to be even more formidable.

Soon, a difficult choice may need to be confronted. Should Greenland’s increasingly accessible resource wealth be aggressively exploited to support and accelerate the global energy transition?

However, undertaking such extraction will exacerbate the impacts of climate change on Greenland and beyond. This includes the degradation of its pristine natural landscapes and contributions to rising sea levels, which could inundate coastal communities.

Presently, all mining and resource extraction activities are subject to stringent regulation by the Greenlandic government, governed by comprehensive legislative frameworks established in the 1970s.

Nevertheless, pressures to relax these regulations and to authorize new permits for exploration and exploitation may intensify, driven by the significant interest shown by the United States in Greenland’s future.

![]()