A neurological affliction of considerable severity, potentially leading to fatality, known as Chiari Malformation Type 1, may be attributable to ancestral interbreeding events between anatomically modern Homo sapiens and Neanderthals that transpired millennia ago. This condition is estimated to affect a significant portion, up to 1%, of the contemporary human population.

A hypothesis posited in 2013 suggests that the genesis of Chiari Malformation Type 1 in individuals stems from certain genes governing cranial development being inherited from three extinct Homo species. These ancient hominins possessed smaller basicrania, or the base of the skull, in contrast to the norm for modern humans: specifically, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, and Homo neanderthalensis. Researchers, including Plomp and colleagues, employed three-dimensional data and sophisticated geometric morphometrics to rigorously examine this proposition. Image courtesy of the Neanderthal Museum.

Chiari Malformation Type 1 is characterized by a disproportionately small posterior cranial vault in humans, which inadequately accommodates the brain. This anatomical discrepancy leads to the caudal displacement of a portion of the cerebellum into the cervical spinal canal.

Such herniation can exert pressure on the affected brain tissue, manifesting in symptoms that range from cervicogenic headaches and neck discomfort to vertigo. In its most acute presentations, the condition can prove lethal if a substantial volume of brain tissue is displaced.

“The scientific endeavor, much like other branches of inquiry, places a premium on elucidating causal pathways,”

“A more profound comprehension of the chain of causality leading to a particular medical ailment enhances the probability of developing effective management strategies, or even complete remediation.”

“While further validation of this hypothesis is warranted, our research may represent a significant stride toward achieving a lucid understanding of the etiological sequence underlying Chiari Malformation Type 1.”

Genetic evidence, uncovered in 2010, confirmed that our species engaged in interbreeding with Neanderthals during prehistoric epochs, stretching back tens of thousands of years.

Individuals of non-African descent currently carry a genetic legacy of 2-5% Neanderthal DNA, a direct consequence of these ancestral hybridization events.

The concept that Chiari Malformation Type 1 might arise from the integration of genes from other hominin lineages into the human genome via interbreeding was initially put forth by Yvens Barbosa Fernandes, a researcher affiliated with the State University of Campinas.

Dr. Fernandes hypothesized that because of the distinct morphological differences between modern human skulls and those of other hominins, the influence of genes from these ancestral species on an individual’s cranial structure could be a contributing factor to the development of the malformation.

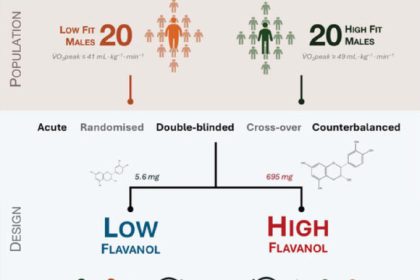

A recent investigation undertaken by Professor Mark Collard of Simon Fraser University, Dr. Kimberly Plomp from the University of the Philippines Diliman, and their research consortium has subjected this theory to empirical scrutiny. Utilizing contemporary medical imaging technologies and advanced analytical techniques for statistical shape analysis, they meticulously compared three-dimensional cranial models derived from living humans—both those diagnosed with Chiari Malformation Type 1 and unaffected individuals—against fossil specimens of hominins. This comparative analysis encompassed ancient Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, Homo heidelbergensis, and Homo erectus.

Their findings revealed a notable convergence in cranial shape traits between individuals afflicted with Chiari malformation and Neanderthals, a pattern not observed in those without the condition.

Intriguingly, the shapes of all other fossil skulls exhibited a greater degree of similarity to the skulls of humans unaffected by Chiari Malformation Type 1. This observation strongly suggests that the observed similarities are not attributable to shared evolutionary lineage but rather lend credence to the hypothesis that certain contemporary individuals possess Neanderthal genes that influence their cranial architecture. This specific cranial morphology, in turn, is theorized to create a structural incongruity between the skull’s form and the morphology of the modern human brain.

It is this resultant anatomical discordance that leads to insufficient cranial space for the brain, thereby compelling its displacement through the only available exit, the spinal canal.

Given the variegated distribution of Neanderthal DNA across global populations, the study forecasts that specific demographic groups, particularly those originating from Europe and Asia, might face an elevated susceptibility to Chiari Malformation Type 1 compared to other populations. Nevertheless, further rigorous inquiry is imperative to definitively substantiate these predictions.

“The study of archaeology and human evolution transcends mere academic curiosity,” stated Professor Collard.

“It possesses the inherent capacity to illuminate our understanding of and, in certain instances, our ability to contend with present-day challenges.”

“In this particular instance, we have leveraged paleontological data to gain insights into a medical condition. However, a plethora of other contemporary issues could benefit from enhanced comprehension through the application of archaeological and paleontological evidence.”

This investigation has been published in the esteemed journal Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health.

_____

Kimberly Plomp et al. 2025. A test of the Archaic Homo Introgression Hypothesis for the Chiari malformation type I. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health 13 (1): 154-166; doi: 10.1093/emph/eoaf009