In a recent scientific investigation, a global consortium of scientists employed sophisticated 3D imaging modalities, including microCT scanning, to digitally reconstruct the cranial morphology of over three dozen distinct taxa. This comprehensive sample encompassed pterosaurs, their immediate evolutionary predecessors, nascent dinosaur lineages, avian progenitors, extant crocodilians and birds, and a broad spectrum of Triassic archosaurs.

Reconstruction of a Late Triassic landscape, approximately 215 million years ago; a lagerpetid, a close relative of pterosaurs, is perched on a rock, observing pterosaurs flying overhead. Image credit: Matheus Fernandes.

The earliest known pterosaurs emerged approximately 220 million years ago, already possessing the capacity for powered flight—an aerial locomotion capability that subsequently evolved independently within the paravian dinosaur clade, which comprises extant birds and their closest extinct relatives.

Flight represents a highly complex mode of locomotion, necessitating substantial physiological adaptations and a radical restructuring of the organismal blueprint. This includes alterations in somatic proportions, development of specialized epidermal coverings, and the acquisition of novel neurosensory faculties.

While pterosaurs and birds independently developed distinct skeletal and integumentary modifications conducive to flight, it is theorized that they shared underlying neuroanatomical characteristics crucial for aerial navigation.

“Our findings corroborate the hypothesis that the enlarged cranial capacities observed in modern birds and presumed in their ancient antecedents were not the primary impetus for pterosaurs’ capacity to achieve flight,” stated Dr. Matteo Fabbri, a researcher affiliated with the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“This investigation demonstrates that pterosaurs achieved flight relatively early in their evolutionary trajectory, and they did so with cranial volumes comparable to those of non-flying dinosaurs.”

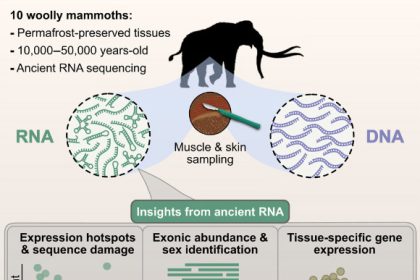

To ascertain whether pterosaurs achieved flight through a different evolutionary pathway than birds and bats, the scientific team meticulously examined the reptilian evolutionary tree. Their objective was to precisely delineate the evolution of pterosaur brain form and dimensions, seeking indicators that might illuminate the development of flight.

Particular attention was directed towards the optic lobe, a region associated with visual processing, the augmentation of which is considered instrumental in the development of aerial capabilities.

Employing CT scanning and advanced imaging software that facilitated the extraction of neural system data from fossilized remains, the researchers focused their analysis on the closest known relative of pterosaurs: Ixalerpeton. This species, a flightless, arboreal inhabitant of Triassic Brazil, dating back to approximately 233 million years ago, belongs to the lagerpetid family.

“The brain of this lagerpetid already exhibited features indicative of enhanced visual acuity, including a notably enlarged optic lobe, an adaptation that may have subsequently aided their pterosaur relatives in achieving flight,” commented Dr. Mario Bronzati from the University of Tübingen.

“A proportionally larger optic lobe was also a characteristic feature observed in pterosaurs,” Dr. Fabbri added.

Notwithstanding these shared traits, significant divergences were noted in the overall shape and size of pterosaur brains when compared with those of their closest flying relatives, the lagerpetids.

“The sparse commonalities suggest that flying pterosaurs, which appeared shortly after the lagerpetids, likely underwent a rapid evolutionary transition to acquire flight at their inception,” Dr. Fabbri explained.

“In essence, pterosaur brains underwent swift transformations, acquiring all necessary neuroanatomical prerequisites for flight from the outset.”

“Conversely, modern avian species are believed to have attained flight through a more iterative, gradual progression. They inherited certain traits, such as an expanded cerebrum, cerebellum, and optic lobes, from their prehistoric ancestors, subsequently refining these structures to facilitate aerial locomotion.”

This theory is further substantiated by a 2024 study that identified the expansion of the cerebellar region as a pivotal factor in avian flight.

The cerebellum, situated at the posterior part of the brain, plays a crucial role in regulating and coordinating muscular movements, among other functions.

In subsequent investigations, the research team meticulously analyzed the endocranial cavities of fossils belonging to crocodilians and early, extinct bird species, conducting a comparative study with pterosaur endocranial cavities.

Their findings indicated that pterosaur brains possessed moderately enlarged cerebral hemispheres, comparable in size to those of other dinosaurs, especially when contrasted with the endocranial volumes observed in modern birds.

“The paleontological discoveries originating from southern Brazil have furnished us with exceptionally valuable new perspectives on the evolutionary origins of major animal lineages, including dinosaurs and pterosaurs,” remarked Dr. Rodrigo Temp Müller, a paleontologist at the Universidade Federal de Santa Maria.

“With each new fossil unearthed and each subsequent study, our comprehension of the early evolutionary stages of these groups becomes increasingly refined, offering insights that might have seemed almost inconceivable just a few years prior.”

“Moving forward, a more profound understanding of how the structural characteristics of the pterosaur brain, in conjunction with its size and shape, facilitated flight will constitute the paramount advancement in accurately inferring the fundamental biological principles governing flight,” Dr. Fabbri concluded.

The outcomes of this research have been published in the esteemed journal Current Biology.

_____

Mario Bronzati et al. Neuroanatomical convergence between pterosaurs and non-avian paravians in the evolution of flight. Current Biology, published online November 26, 2025; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.10.086