When you navigate the digital realm, who is observing your actions?

During a recent period of online exploration, I conducted an examination of Google Chrome and discovered that it was accompanied by a myriad of tracking elements. Websites related to commerce, news, and even governmental services were covertly appending identifiers to my browser, enabling advertising and data firms to gain access to my browsing activities.

This pervasive tracking is orchestrated by the most prolific data collector on the internet: Google. From an internal perspective, its Chrome browser functions akin to sophisticated surveillance software.

My recent investigations have delved into the hidden lifecycle of personal data, involving experiments designed to reveal the actual operations of technology operating under the guise of unread privacy policies. It appears that entrusting the world’s preeminent advertising entity with the development of the most widely utilized web browser was an imprudent decision, comparable to allowing children to manage a confectionery establishment.

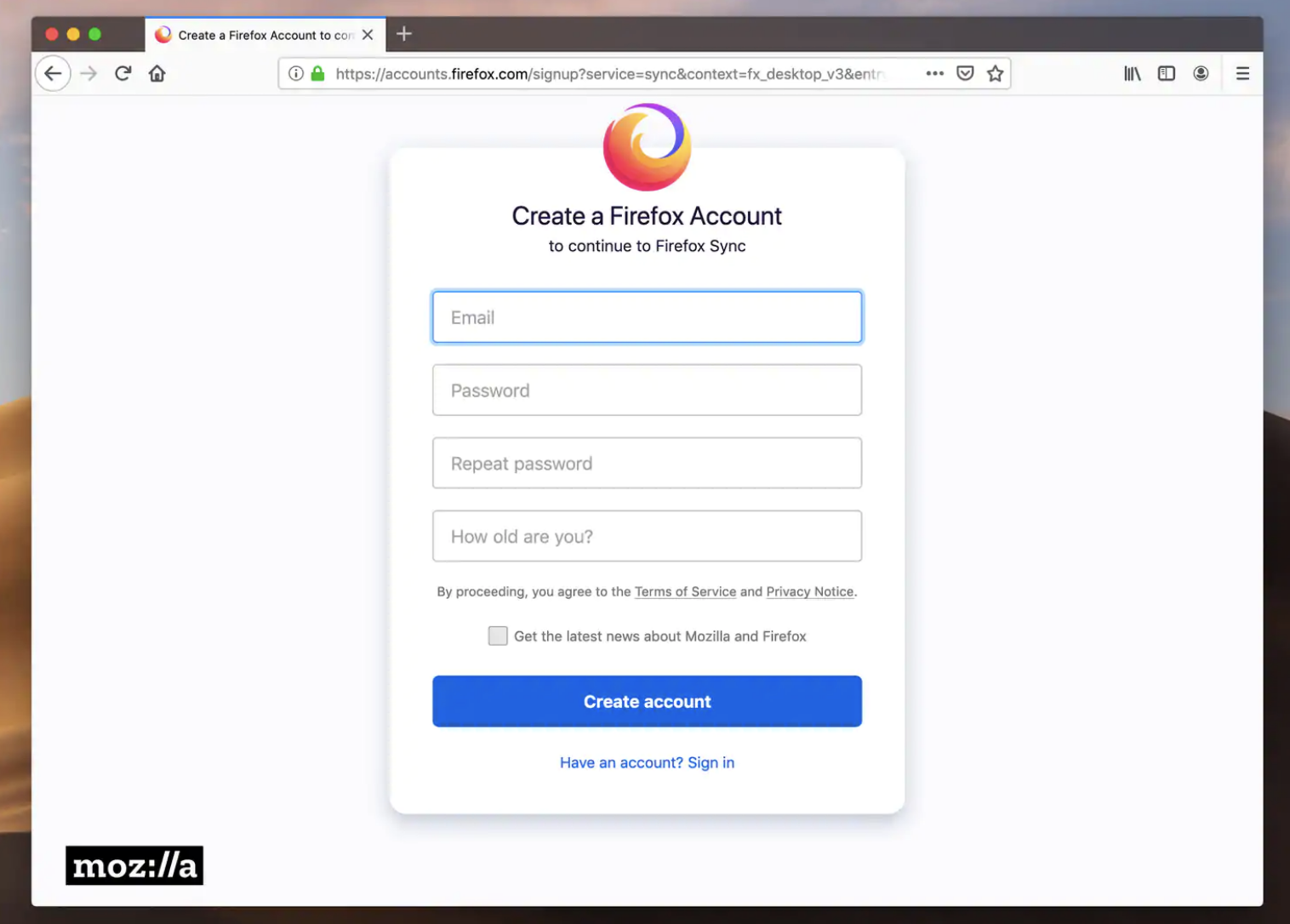

This realization prompted my decision to transition away from Chrome and adopt a newer iteration of the non-profit Mozilla Firefox, which incorporates default privacy safeguards. The process of switching proved to be less cumbersome than anticipated.

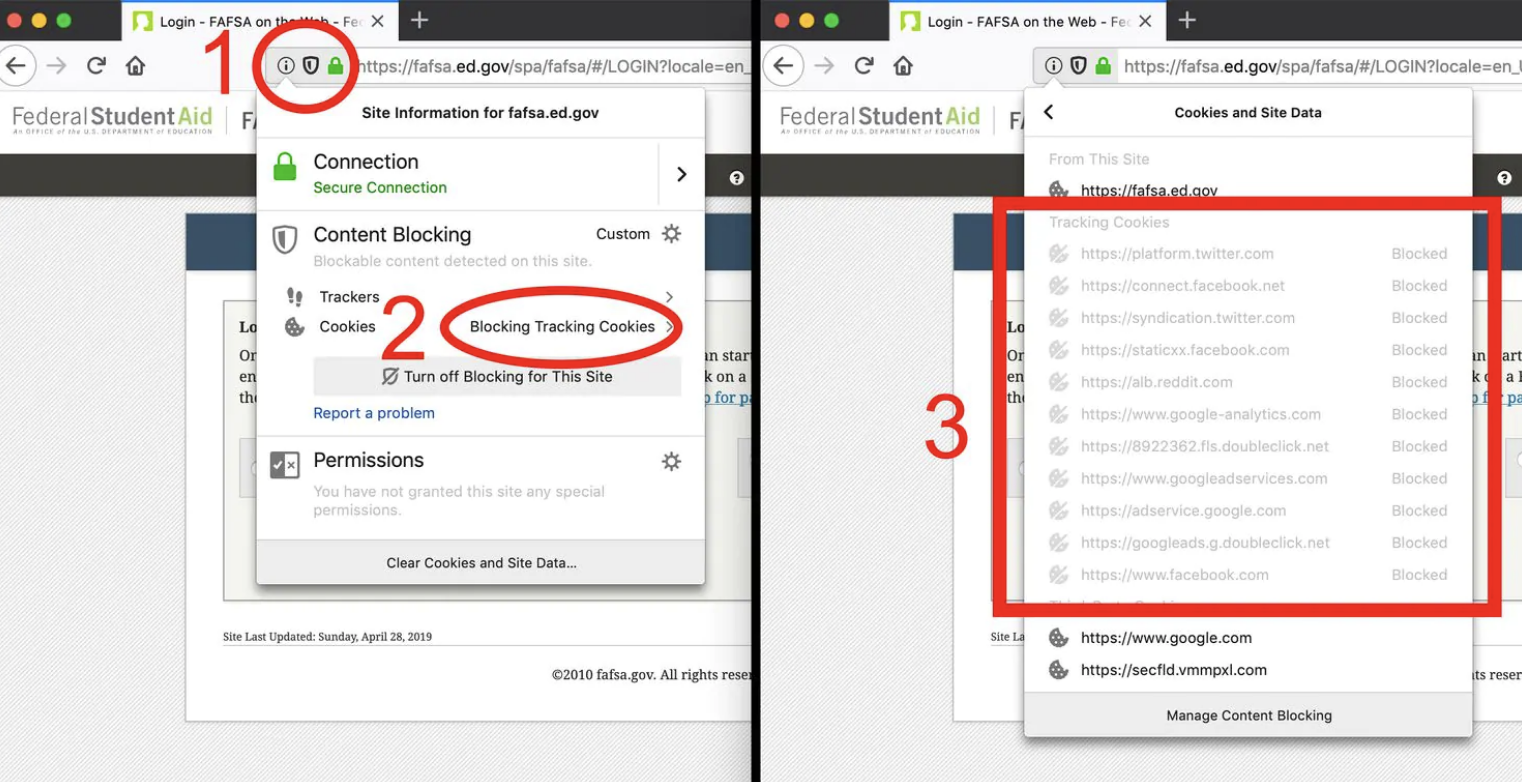

My comparative analysis of Chrome and Firefox uncovered a personal data transgression of remarkable scale. Over one week of desktop web browsing, I identified 11,189 requests for tracking “cookies” that Chrome would have readily installed on my system, whereas Firefox automatically prevented them. These diminutive files serve as conduits for data aggregation firms, including Google itself, to monitor your web traversals and compile profiles of your interests, financial standing, and personality traits.

Chrome permitted the installation of trackers even on websites that one would expect to maintain strict privacy. I observed Aetna and the Federal Student Aid website establishing cookies for Facebook and Google. These actions surreptitiously informed these data conglomerates every instance I accessed the login pages for these insurance and loan services.

And that is merely the beginning of the story.

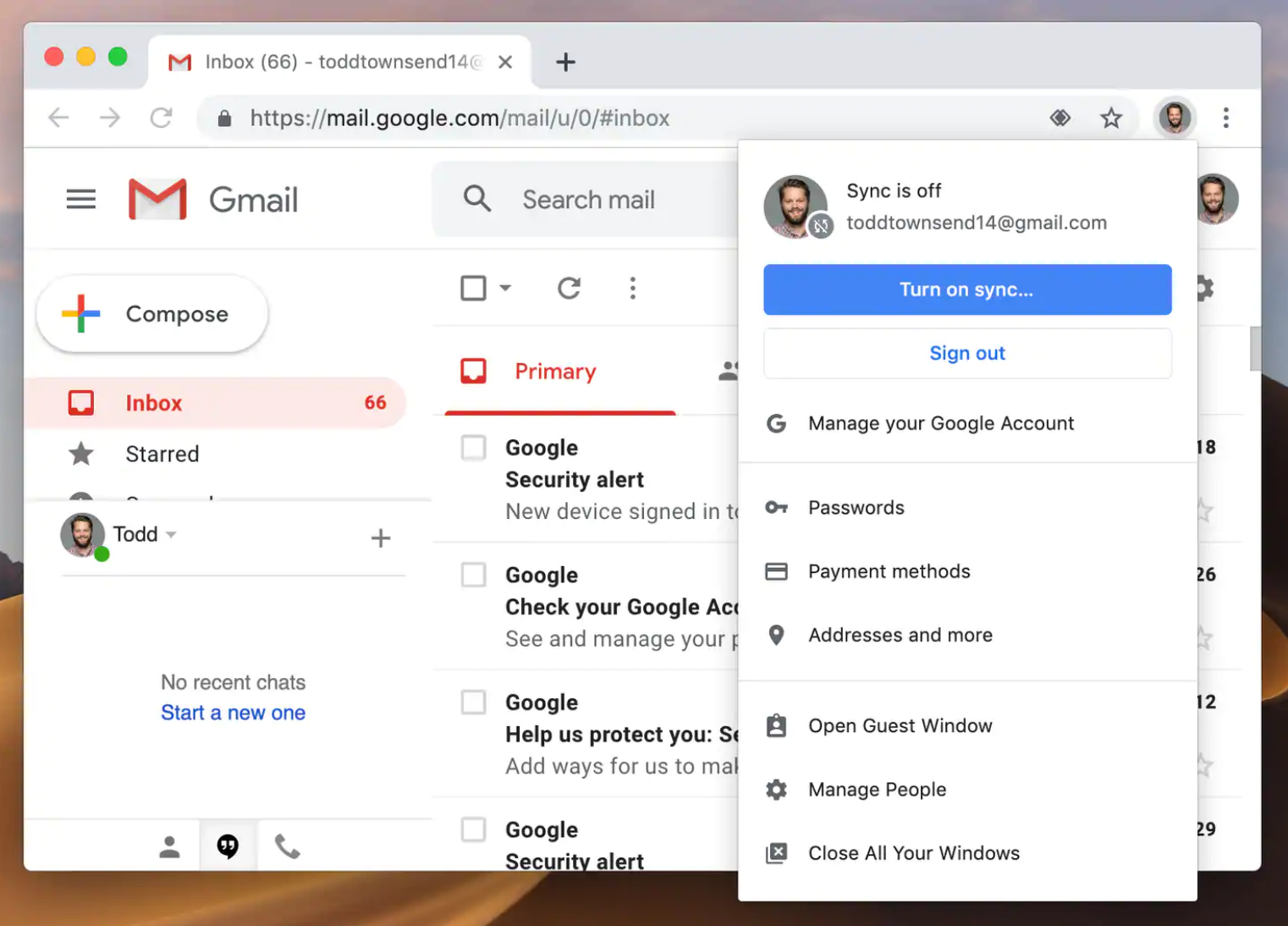

Direct your attention to the upper-right quadrant of your Chrome browser interface. Do you observe an image or a name enclosed within a circular emblem? If so, you are currently signed into the browser, and Google may be leveraging your online activities for targeted advertising. Do you not recall initiating this login? Neither did I. Chrome has recently implemented this feature automatically when you engage with Gmail.

Chrome exhibits even greater intrusiveness on mobile devices. For Android users, Chrome transmits your location data to Google with every search query you initiate. (Even when location sharing is deactivated, it continues to transmit your coordinates, albeit with reduced precision.)

While Firefox is not entirely flawless, it still defaults search queries to Google and permits certain other forms of tracking. However, it refrains from sharing browsing data with Mozilla, an organization that does not engage in the business of data collection.

At a minimum, online surveillance can be an irritant. Cookies facilitate the phenomenon where an item you examine on one website subsequently appears in advertisements across other platforms. More fundamentally, your browsing history—akin to the color of your undergarments—is private information that should not be accessible to others. Permitting any entity to amass such data renders it susceptible to exploitation by malicious actors, including bullies, spies, and hackers.

In discussions with Google’s product managers, they asserted that Chrome places a premium on user privacy settings and controls, and that they are actively developing enhancements for cookie management. Concurrently, they acknowledged the necessity of striking a balance with a “healthy Web ecosystem,” which implicitly signifies the advertising industry.

Firefox’s product management team conveyed that they do not perceive privacy as a mere “option” confined to settings. They have initiated a concerted effort against pervasive tracking, beginning this month with “enhanced tracking protection,” which by default blocks intrusive cookies on newly installed Firefox versions. However, to achieve widespread adoption, Firefox must first motivate users to overcome the inherent inertia associated with transitioning to a new browser.

This narrative presents a dichotomy of browsers and reflects the divergent interests of their respective developers.

(Geoffrey Fowler/The Washington Post)

(Geoffrey Fowler/The Washington Post)

The Conflict Over Cookies

A decade ago, Chrome and Firefox emerged as formidable challengers to Microsoft’s dominant Internet Explorer. Chrome, an innovative newcomer, addressed significant user issues, enhancing both web security and speed. Today, it commands a substantial portion of the market.

However, in recent times, a growing awareness of privacy concerns has surfaced, and Chrome’s objectives no longer consistently align with those of its users.

This divergence is most evident in the ongoing contention surrounding cookies. These small script fragments can serve beneficial purposes, such as retaining items in a user’s virtual shopping cart. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of contemporary cookies are owned by data corporations, which employ them to tag browsers and meticulously track user navigation, much like leaving a trail of breadcrumbs in a dense forest.

These trackers are ubiquitous. According to one research study, third-party tracking cookies were detected on an astonishing 92 percent of surveyed websites. The Washington Post website deploys approximately 40 tracker cookies, a typical number for a news publication, which the company stated are utilized to deliver more relevant advertisements and evaluate campaign efficacy.

These cookies are also present on websites that do not feature advertising. Both Aetna and the FSA service indicated that the cookies implemented on their platforms aid in assessing the performance of their external marketing initiatives.

The responsibility for this pervasive tracking issue extends across the advertising, publishing, and technology sectors. However, the question arises: what obligation does a web browser bear in safeguarding users from code that primarily serves surveillance purposes?

(Geoffrey Fowler/The Washington Post)

(Geoffrey Fowler/The Washington Post)

In 2015, Mozilla introduced a version of Firefox incorporating anti-tracking technology, which was initially confined to its “private” browsing mode. Following extensive testing and refinement, this functionality has now been activated across all websites. The objective is not to obstruct advertisements, which continue to be displayed. Rather, Firefox analyzes cookies to discern which are essential for site functionality and which are employed for surveillance purposes, subsequently blocking the latter.

Apple’s Safari browser, predominantly used on iPhones, initiated the implementation of “intelligent tracking protection” for cookies in 2017. This feature employs an algorithmic approach to identify and mitigate problematic cookies.

Chrome, to date, continues to permit all cookies by default. Last month, Google announced a new initiative to compel third-party cookies to self-identify more transparently, and indicated that enhanced controls for these cookies would be introduced post-implementation. However, no specific timeline was provided, nor was it clarified whether the default setting would involve blocking trackers.

My optimism regarding swift action is tempered. Google, through its Doubleclick and other advertising ventures, ranks as the preeminent entity in cookie creation—often referred to as the “Mrs. Fields” of the online world. It is improbable that Chrome will ever implement measures that would compromise Google’s primary revenue stream.

“While cookies play a role in user privacy, an exclusive concentration on cookies can overshadow the broader privacy discourse, as it represents only one avenue through which users can be tracked across various sites,” stated Ben Galbraith, Chrome’s Director of Product Management. “This is an intricate challenge, and simplistic, rigid cookie blocking solutions tend to drive tracking into less transparent methodologies.”

Additional tracking methodologies exist, and the ongoing evolution of privacy safeguards will present escalating complexities. However, invoking complexity as a rationale for inaction is an unproductive strategy.

“Our perspective is to address the most significant issue first, while simultaneously anticipating emergent trends within the ecosystem and developing protective measures against those as well,” commented Peter Dolanjski, Firefox’s Product Lead.

Both Google and Mozilla affirmed their commitment to combating “fingerprinting,” a technique used to identify other unique markers on a user’s computer. Firefox is currently evaluating its capabilities and intends to deploy them in the near future.

Facilitating the Transition

The selection of a web browser transcends mere considerations of speed and convenience; it now encompasses the default data handling practices.

It is acknowledged that Google typically obtains user consent before collecting data and provides a plethora of customizable options to opt out of tracking and targeted advertising. Nevertheless, its control mechanisms often resemble a deceptive maneuver, ultimately leading to the disclosure of more personal information.

I experienced a sense of deception when Google autonomously initiated the process of logging Gmail users into Chrome in the autumn of last year. Google asserts that this shift in Chrome’s behavior did not result in the “syncing” of any browsing history without explicit user opt-in. However, my own browsing history was transmitted to Google, and I have no recollection of authorizing this additional level of surveillance. (This Gmail auto-login feature can be deactivated by searching for “Gmail” within Chrome’s settings and toggling off “Allow Chrome sign-in.”)

Following this significant login modification, Matthew Green, an associate professor at Johns Hopkins University, garnered considerable attention within the computer science community for his blog post announcing his decision to cease using Chrome. He conveyed his loss of confidence, stating, “Even a few minor adjustments can render it significantly detrimental to privacy.”

(Geoffrey Fowler/The Washington Post)

(Geoffrey Fowler/The Washington Post)

While measures exist to mitigate Chrome’s tracking capabilities, these are considerably more intricate than simply utilizing “Incognito Mode.” However, transitioning to a browser not owned by an advertising entity presents a far more straightforward solution.

Similar to Professor Green, I have opted for Firefox, which offers seamless functionality across smartphones, tablets, PCs, and Macs. Apple’s Safari is also a viable alternative for users of Macs, iPhones, and iPads, while the specialized Brave browser adopts a more aggressive stance in combating the advertising technology industry.

What is the cost of migrating to Firefox? It is entirely free, and the process of downloading an alternative browser is significantly less involved than replacing a mobile device.

In 2017, Mozilla unveiled an updated version of Firefox named Quantum, which introduced substantial improvements in speed. My personal experience indicates that its performance is comparable to Chrome’s, although benchmark evaluations suggest it may exhibit slower performance in specific scenarios. Firefox claims superior memory management capabilities when handling a large number of open tabs.

The transition necessitates the relocation of your bookmarks, and Firefox provides tools to facilitate this process. The migration of passwords is simplified if you utilize a password management solution. While most browser extensions are compatible, it is possible that certain preferred add-ons may not be available.

Mozilla faces its own set of challenges. Within privacy advocacy circles, the non-profit organization is recognized for its measured approach. It took a year longer than Apple to implement default cookie blocking.

Furthermore, as a non-profit entity, Mozilla generates revenue through user searches conducted within its browser and subsequent ad clicks. Consequently, its primary income source is derived from Google. The chief executive of Mozilla has indicated that the company is exploring the development of paid privacy services to diversify its revenue streams.

The most significant potential risk is that Firefox might eventually falter in its competition against the dominant Chrome platform. Despite holding the position of the second-largest desktop browser, with approximately 10 percent market share, major websites could conceivably discontinue support, leaving Firefox in a precarious situation.

For individuals prioritizing privacy, one can only hope for a recurrence of the David and Goliath narrative.

The perspectives articulated in this article do not necessarily reflect the official viewpoints of ScienceAlert’s editorial team.

This feature was originally published by The Washington Post.