Extracting detailed biochemical insights from ancient, organic-rich geological strata, particularly the chronological sequence of the advent of photosynthesis in relation to the inferred oxygenation of our planet’s atmosphere, presents an ongoing and formidable scientific endeavor. To address this complex challenge, investigators undertook an analysis of 406 varied ancient and contemporary specimens, employing supervised machine learning algorithms to distinguish between samples of biological versus non-biological origin, as well as photosynthetic versus non-photosynthetic life forms. Their findings revealed chemical indicators of biogenic molecular assemblages within Paleoarchean rock formations (dating back 3.51 billion years) and evidence of photosynthetic life in Neoarchean rocks (from 2.52 billion years ago).

The earliest manifestations of life on Earth left behind a paucity of molecular residues.

The scarce, delicate traces, such as primordial cells and microbial mats, were subjected to burial, compression, thermal alteration, and fracturing within Earth’s dynamic lithosphere before their eventual emergence at the surface.

These transformative geological processes profoundly degraded the biosignatures, which held crucial information regarding the genesis and early evolutionary trajectory of life.

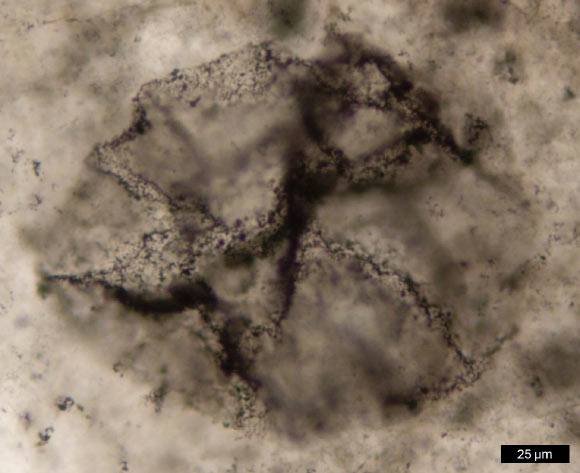

Paleobiologists dedicated to the investigation of Earth’s most venerable life forms have historically relied predominantly on fossilized organisms. This includes microscopic cellular fossils and filamentous structures, in addition to the mineralized remnants of cellular organizations, like microbial mats and stromatolite formations, which offer compelling evidence of life dating back as far as 3.5 billion years. However, such fossilized remains are exceptionally rare and scattered.

A supplementary avenue of inquiry involves the preservation of distinctive biomolecules within ancient geological deposits.

The most resilient organic molecules produced by life—those originating from cellular membranes or specific metabolic pathways—have been identified in sedimentary layers as old as 1.7 billion years. Furthermore, significantly older carbon-rich rocks exhibit isotopic signatures that suggest the existence of a thriving biosphere approximately 3.5 billion years ago.

Nevertheless, the preponderance of ancient rock formations lacks evidence of either fossilized cells or any surviving biomolecules.

The overwhelming majority of ancient carbonaceous sediments have undergone thermal and chemical alterations that disintegrate every characteristic biomolecule into innumerable minute fragments.

Up to this point, these fragments have been too minuscule and too generalized to yield any clues about ancient life.

“Ancient geological formations present numerous intriguing puzzles that narrate the history of life on our planet, yet certain pieces of this narrative are consistently absent,” stated Katie Maloney, a researcher at Michigan State University and co-author of the study.

“The synergy between chemical analysis and machine learning has unveiled biological indicators of ancient life that were previously imperceptible.”

Organic matter extracted from samples of 2.5-billion-year-old rock containing fossilized microorganisms like the one in this photomicrograph still contains biomolecular fragments that may have been produced via photosynthesis. Image credit: Andrew D. Czaja.

The investigative team employed sophisticated high-resolution chemical analytical techniques to deconstruct organic and inorganic materials into their constituent molecular fragments. Subsequently, an artificial intelligence system was trained to recognize the specific chemical signatures imparted by biological entities.

A comprehensive examination was performed on a total of 406 samples, encompassing fossilized organisms, modern biological specimens, meteoritic material, and synthetic compounds.

The AI model demonstrated a classification accuracy exceeding 90% in differentiating between biological and non-biological substances, and it identified the earliest biomolecular evidence pertaining to:

(i) The photosynthetic origins of organic molecules found within the 2.52-billion-year-old Gamohaan Formation, Campbellrand Group, South Africa, and the 2.30-billion-year-old Gowganda Group, Ontario, Canada;

(ii) The biogenicity of organic molecules preserved in the 3.51-billion-year-old Singhbhum Craton, India; the 3.33-billion-year-old Josefsdal Chert of the Barberton Greenstone Belt, South Africa; and the 2.66-billion-year-old Jerrinah Formation, Fortescue Group, Pilbara Craton, Australia;

(iii) And the seemingly non-photosynthetic origin of organic species identified in the 3.5-billion-year-old Theespruit Formation, Barberton Greenstone Belt, South Africa, and the 3.48-billion-year-old Dresser Formation, Pilbara Craton, Australia.

“Ancient life leaves behind more than just discernible fossils; it leaves behind chemical reverberations,” commented Dr. Robert Hazen, senior author and a researcher at the Carnegie Institution for Science.

“Through the application of machine learning, we are now capable of reliably interpreting these residual chemical signals for the first time.”

“This pioneering methodology allows us to interpret the fossil record of deep time through a novel perspective,” Dr. Maloney added.

“This could prove instrumental in guiding the search for extraterrestrial life.”

“Comprehending the timing of photosynthesis’s emergence is crucial for understanding the evolution of Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere, a pivotal development that facilitated the emergence of complex organisms, including humans,” explained Dr. Michael Wong, the lead author and also affiliated with the Carnegie Institution for Science.

“This study serves as an exemplary demonstration of how contemporary technological advancements can illuminate the most ancient narratives of our planet and possesses the potential to transform our methodologies for seeking ancient life, both on Earth and on other celestial bodies.”

“Looking ahead, our intentions include evaluating materials such as anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria—which may serve as analogs for extraterrestrial life forms. This represents a potent new instrument for astrobiological exploration.”

“These geological samples and the spectral signatures they produce have been subjects of extensive study for decades, but AI offers a powerful new analytical lens that enables us to extract critical information and achieve a more profound understanding of their inherent characteristics,” remarked Dr. Anirudh Prabhu from the Carnegie Institution for Science, a co-author of the research.

“Even in instances where degradation makes direct identification of life challenging, our machine learning models are proficient at detecting the subtle imprints left by ancient biological processes.”

“The compelling aspect is that this approach does not necessitate the discovery of recognizable fossils or intact biomolecules.”

“Artificial intelligence not only expedited our data analysis but also empowered us to derive meaning from complex and degraded chemical datasets.”

“This innovation opens avenues for investigating ancient and extraterrestrial environments with a fresh analytical framework, guided by patterns that might otherwise elude human observation.”

The team’s findings are published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____

Michael L. Wong et al. 2025. Organic geochemical evidence for life in Archean rocks identified by pyrolysis-GC-MS and supervised machine learning. PNAS 122 (47): e2514534122; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2514534122