For the past two decades, the prevailing paradigm in human evolutionary genetics posited that Homo sapiens originated in Africa approximately 200,000 to 300,000 years ago, evolving from a singular ancestral lineage. Nonetheless, recent investigations emanating from the University of Cambridge propose a divergent perspective: modern humans are the consequence of an admixture event between two distinct populations, potentially Homo heidelbergensis and Homo erectus. These ancestral groups are theorized to have separated 1.5 million years ago and subsequently coalesced approximately 300,000 years ago, contributing in an approximate 80:20 ratio to the modern human genome.

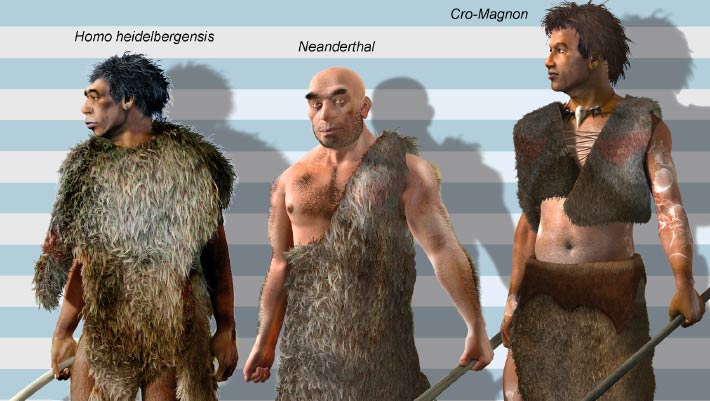

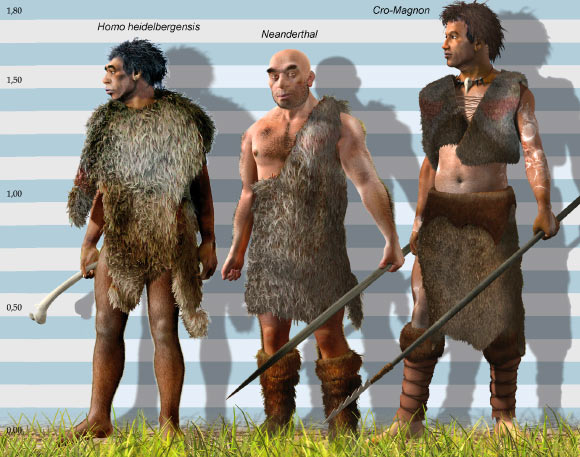

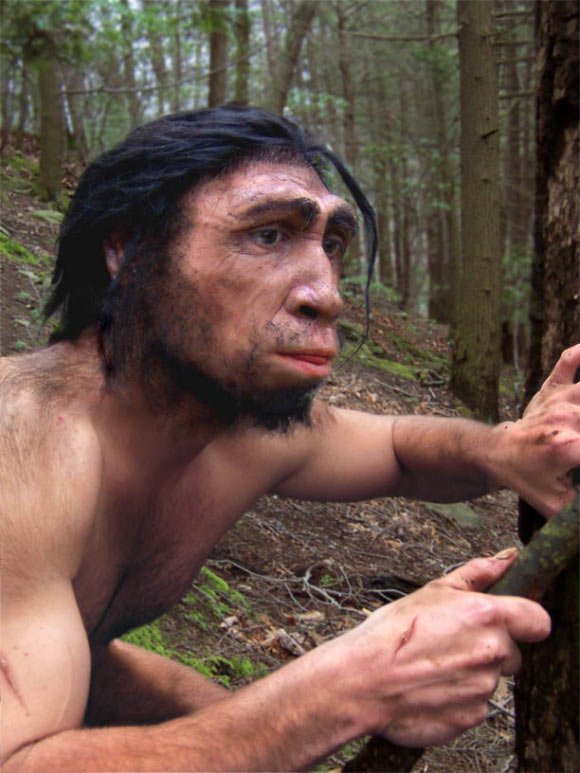

A Homo heidelbergensis, a Neanderthal and a Cro-Magnon. Image credit: SINC / José Antonio Peñas.

“The enigma of our origins has captivated humanity for millennia,” remarked Dr. Trevor Cousins of the University of Cambridge.

“For an extended period, the consensus held that our evolution stemmed from a single, unbroken ancestral line, though the precise delineations of our genesis remain elusive.”

“Our findings provide compelling evidence that our evolutionary trajectory is considerably more intricate, involving separate developmental pathways for distinct groups over more than a million years before their subsequent reunion to form the contemporary human species,” elaborated Professor Richard Durbin, also from the University of Cambridge.

Whereas prior investigations had elucidated interbreeding between Neanderthals and Denisovans with Homo sapiens around 50,000 years ago, this new research indicates a far more significant genetic amalgamation occurred considerably earlier—approximately 300,000 years ago.

Contrary to the Neanderthal DNA, which constitutes roughly 2% of the genome in non-African modern humans, this ancient intermingling event contributed as much as tenfold that proportion and is discernible in all extant human populations.

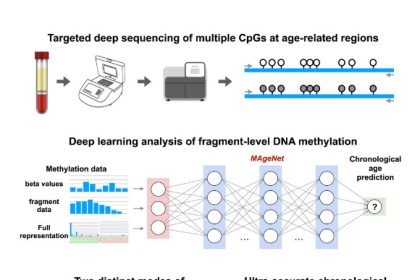

The research methodology employed by the team involved the analysis of contemporary human genetic material, foregoing the extraction of DNA from ancient skeletal remains. This approach facilitated the inference of ancestral populations that might otherwise have left no discernible fossil record.

The researchers devised a computational framework, christened ‘cobraa’, designed to simulate the processes by which ancient human populations diverged and subsequently reintegrated.

This algorithm was rigorously evaluated using both simulated datasets and actual human genetic data derived from the 1000 Genomes Project, a global endeavor that cataloged the DNA sequences of populations spanning Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

Beyond identifying these two ancestral progenitors, the scientists also detected notable evolutionary shifts that transpired subsequent to the initial divergence of the two lineages.

“Immediately following the separation of the two ancestral groups, we observe a pronounced population bottleneck within one of them—suggesting a drastic reduction in size before a gradual expansion over a period of one million years,” stated Professor Aylwyn Scally of the University of Cambridge.

“This preponderant lineage ultimately accounted for approximately 80% of the genetic makeup of modern humans and appears to be the ancestral line from which Neanderthals and Denisovans subsequently branched off.”

“Nevertheless, certain genetic contributions from the minority ancestral population, particularly those associated with cognitive functions and neural processing, may have played a pivotal role in the evolutionary narrative of humanity,” commented Dr. Cousins.

This is an artist’s reconstruction of Homo erectus. Image credit: Yale University.

The scientific team further discerned that genetic elements inherited from the secondary ancestral group were frequently situated in genomic regions less associated with established gene functions, intimating a potentially reduced compatibility with the dominant genetic background.

This observation lends credence to a process known as purifying selection, whereby natural selection acts to eliminate detrimental genetic mutations over time.

Consequently, the identity of our enigmatic human antecedents remains a subject of ongoing inquiry. Fossil evidence points towards species such as Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis, whose geographic distribution encompassed both Africa and other continents during the relevant epoch, as plausible candidates for these ancestral populations. However, further rigorous investigation, potentially accompanied by additional paleontological discoveries, will be imperative to conclusively link specific genetic ancestors with particular fossil records.

Looking toward future research, the authors aim to refine their computational model to incorporate more nuanced and gradual genetic exchanges between populations, moving beyond simpler representations of distinct separations and reunions.

Their future endeavors also include exploring the correlations between their findings and other anthropological insights, such as fossil evidence from Africa that suggests a greater degree of diversity among early hominins than was previously hypothesized.

“The capacity to reconstruct events spanning hundreds of thousands or even millions of years solely through the examination of contemporary DNA is profoundly astonishing,” Professor Scally expressed.

“It unequivocally demonstrates that our evolutionary history is far more variegated and intricate than we had hitherto imagined.”

This groundbreaking investigation has been published in the esteemed journal Nature Genetics.

_____

T. Cousins et al. A structured coalescent model reveals deep ancestral structure shared by all modern humans. Nat Genet, published online March 18, 2025; doi: 10.1038/s41588-025-02117-1