On May 11th, Saturday, researchers stationed at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii reached a significant milestone for humanity: atmospheric carbon dioxide levels surpassed 415 parts per million. This concentration is unprecedented in millions of years. Truly remarkable times we are living in.

Towards the close of the past week, the British publication, The Guardian, unveiled a revision to its editorial guidelines. Henceforth, the newspaper will advocate for terminology such as ‘climate crisis’ or ‘breakdown’ and ‘global heating’ over the more conventionally employed expressions ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’.

This modification in language by the media outlet has elicited both commendation and accusations of fearmongering. Nevertheless, it prompted introspection within ScienceAlert regarding our own publication’s nomenclature.

Prior to implementing any substantial alterations, I opted to engage with individuals at the forefront of this discourse – the scientific community. Are we, as members of the press, justified in characterizing this as a climate crisis?

“The appropriate media discourse on climate change is not a novel debate,” informed Jessica Hellmann, a preeminent ecology researcher and director of the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment, to ScienceAlert.

“For a quarter-century or more, climate scientists have critiqued the media’s default stance of providing ‘balanced’ coverage for climate change, granting equal prominence to rigorously peer-reviewed research and less substantiated assertions and counterarguments.”

Hellmann points out that this issue of false balance has diminished in recent years, and she believes a linguistic shift “represents the subsequent phase in that progression, aiming to more accurately portray the ramifications of climate change for the public’s benefit.”

To identify widespread instances of the term ‘climate crisis’ across the digital landscape, one need only consider US politician Al Gore. His 2008 TED talk, titled “New thinking on the climate crisis,” has garnered over 2 million views.

However, the adoption of this terminology is not confined to activist circles. Among scientific professionals, the phrase ‘climate crisis’ is far from a recent invention. A cursory examination of Google Scholar readily reveals thousands of academic papers, book chapters, and other scholarly works that explicitly refer to it as a crisis, often within their titles.

Consequently, it appears to be a minimal leap to begin incorporating this designation more prominently into media reporting as well.

“I believe the judicious selection of language and imagery is paramount,” stated Stephan Lewandowsky, a cognitive psychologist at the University of Bristol specializing in public perception of climate change.

“Regarding the specific term ‘climate crisis,’ I find that it achieves an appropriate equilibrium, conveying urgency without resorting to hyperbole.”

It wasn’t initially framed as a crisis

“Arguably more than most other scientific principles, the evidence substantiating climate change is rooted in statistical analyses derived from innumerable observations spanning both temporal and spatial dimensions,” Lewandowsky and his colleague Lorraine Whitmarsh articulated in a PLOS Biology publication last year.

Such dispersed evidence and the extensive timescales involved render it a challenging subject to fully comprehend, certainly. Therefore, it is unsurprising that the language employed in publicly communicating the findings of climate change science has undergone considerable transformation over the preceding decades.

“Scientists typically adopt a cautious tone when detailing their research and discuss the implications within the framework of probabilities,” a 2007 paper concerning media coverage of climate change observed.

“For journalists and policymakers, this presents a difficulty in translation into the concise, unambiguous commentary that is frequently valued in communication and decision-making processes.”

It was around the 1980s that the general populace began to acknowledge the “greenhouse effect,” the fundamental principle of atmospheric warming first posited by several scientists in the mid-19th century. (Indeed, awareness of the threat posed by unrestrained fossil fuel consumption has existed for a considerable period, as evidenced by a 1912 newspaper clipping originating from New Zealand.)

As global temperatures began to establish new records in the late 1980s, the term “global warming” entered public awareness, closely followed by “climate change” itself. After all, the inaugural report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was disseminated in 1990.

With escalating public interest in climate change throughout the 2000s and early activism culminating in Gore’s documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, we also witnessed increased political polarization regarding appropriate responses. Or even whether any action was warranted, or if the phenomenon was indeed real.

By this juncture, “global warming” and “climate change” had become largely interchangeable in news reporting, despite possessing distinct scientific connotations. This linguistic ambiguity has persisted, with some ScienceAlert readers even attempting to assert that the term “global warming” is now obsolete.

The reality is that “global warming” conveys a greater sense of peril and immediacy, strongly implying that adverse consequences are inevitable.

The current US President, Donald Trump, tweeted in 2013 that the nomenclature had been altered from “global warming” to “climate change” because the former “wasn’t working.” However, if any entity can claim original credit for manipulating scientific terminology to influence public opinion, it is arguably the George W. Bush administration – and their motivation was precisely because it *was* working too effectively.

A 2002 internal memorandum to Bush, authored by political strategist Frank Luntz, famously recommended that “‘climate change’ is less frightening than ‘global warming’,” alongside suggestions to continue fostering skepticism regarding the established scientific consensus on climate science.

The memo proved efficacious.

Let’s be adults about it

As governmental administrations have transitioned over time, the planetary processes we categorize as climate change have unrelentingly progressed, with each subsequent scientific report detailing their escalating impacts demanding greater urgency.

“The vocabulary we employ has not kept pace with the scientific realities of climate change. The words we select shape our cognitive frameworks for understanding a problem,” remarked philosopher Clive Hamilton, who has extensively documented humanity’s struggle with climate change through a series of books.

“For years, the fainthearted have advised against being ‘alarmist,’ positing that frightening the public would lead to disengagement,” he disclosed to ScienceAlert. “However, we ought to treat the public with the respect due to adults and present them with the unvarnished truth.”

Indeed, in certain respects, we have moved beyond merely debating whether ‘global warming’ sounds alarming. For a significant portion of the population, particularly younger generations, the situation is terrifying, and they are motivated to take action. From school walkouts to advocacy for policies promoting carbon emission reductions, there is a palpable resurgence in the call for decisive measures.

“We must apprise the public of the enormity of the challenge without, however, instilling a sense of futility,” Stephan Lewandowsky advised ScienceAlert. “The term ‘crisis’ effectively serves this objective and is undeniably more fitting than the rather anodyne ‘climate change’.”

Similarly, there exists substantial scientific evidence to indicate that the planet is experiencing more than just gradual warming.

“While the potential for causing confusion always exists, ‘global heating’ offers a more precise depiction of the actual unfolding events compared to ‘global warming’,” observed Jessica Hellmann.

Will Steffen, a climate scientist and Councillor with the Climate Council of Australia, also advocates for more robust language concerning climate change, alongside the imperative actions required.

“‘Climate crisis’ is likely an appropriate designation at this juncture,” he informed ScienceAlert.

“Another critical concept to convey is the profound impact of emission reduction decisions made now on averting potentially catastrophic transformations later in the century. The phrase ‘point of no return’ could be beneficial in this context.”

Alienating the doubtful

Despite these various linguistic shifts in media representation – ranging from the ‘greenhouse effect’ to the ‘climate crisis’ – a segment of the populace remains skeptical regarding the true scope of climate change. Others deny human activity as its primary driver, and some even reject established scientific facts outright.

The Guardian‘s revised style guide advocates for labeling such individuals as “climate deniers” rather than skeptics, thereby underscoring that this is not a matter of balancing opinions. ScienceAlert currently employs similar phrasing: the factual underpinnings of climate science are not subject to debate, and we treat them accordingly.

Nonetheless, the successful rebranding of climate change to a “crisis,” “breakdown,” or “emergency” is contingent upon understanding the target audience and the desired outreach.

This lesson is unequivocally clear to atmospheric scientist Katharine Hayhoe, recognized as one of the world’s most influential communicators on climate change.

“In my estimation, the scientific evidence, coupled with our current upward trajectory in carbon emissions rather than a decline, unequivocally justifies the term ‘climate crisis’,” she stated to ScienceAlert.

However, she cautions that such framing is primarily “effective for those who are already concerned about climate change but remain complacent regarding solutions, viewing it as a concern for future generations rather than an immediate threat.” Hayhoe suggests this demographic likely encompasses a majority of The Guardian‘s readership.

“Conversely, it has not yet proven effective for individuals who already perceive proponents of climate action as alarmist ‘Chicken Littles.’ Instead, it would further solidify their preconceived – and erroneous – notions.”

Let’s be precise

In summation, we have reached a consensus. A substantial body of evidence and expert opinion supports the notion that the ‘crisis’ designation is not baseless alarmism; indeed, it holds a valid place in our discourse on climate change, and an increased prevalence of ‘crisis’ terminology is anticipated. This will likely occur even amidst ongoing disagreement from some quarters.

Nevertheless, characterizing the impact of climate change as a crisis cannot supersede the established scientific terminology we already employ.

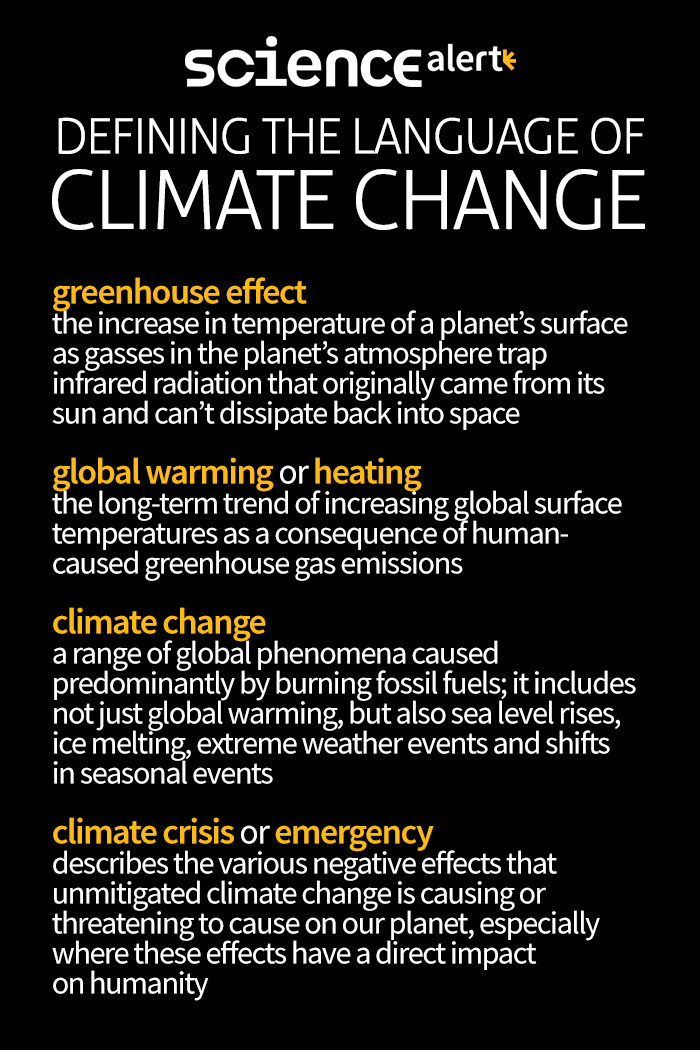

With these considerations firmly in mind, ScienceAlert will henceforth utilize the following definitions for climate science-related terms:

greenhouse effect: The phenomenon wherein atmospheric gases trap thermal energy radiating from celestial bodies, leading to an elevation in a planet’s surface temperature;

global warming (or heating): The sustained trend of escalating global surface temperatures resulting from anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions;

climate change: A spectrum of widespread environmental phenomena primarily induced by fossil fuel combustion, encompassing not only global warming but also phenomena such as sea-level rise, glacial melt, extreme weather events, and alterations in seasonal patterns;

climate crisis or emergency: A descriptor for the manifold adverse consequences that unmitigated climate change is currently inflicting or is poised to inflict upon our planet, particularly where these effects have a direct and tangible impact on human societies.