An analysis of ancient proteins has confirmed that a fossilized mandible, retrieved from the Penghu Channel in Taiwan during the 2000s and estimated to be between 190,000 and 10,000 years old, originated from a male Denisovan. This significant finding offers tangible proof of Denisovan habitation across a broad spectrum of environmental conditions, extending from the frigid Siberian highlands to the warm, humid subtropical zones of Taiwan.

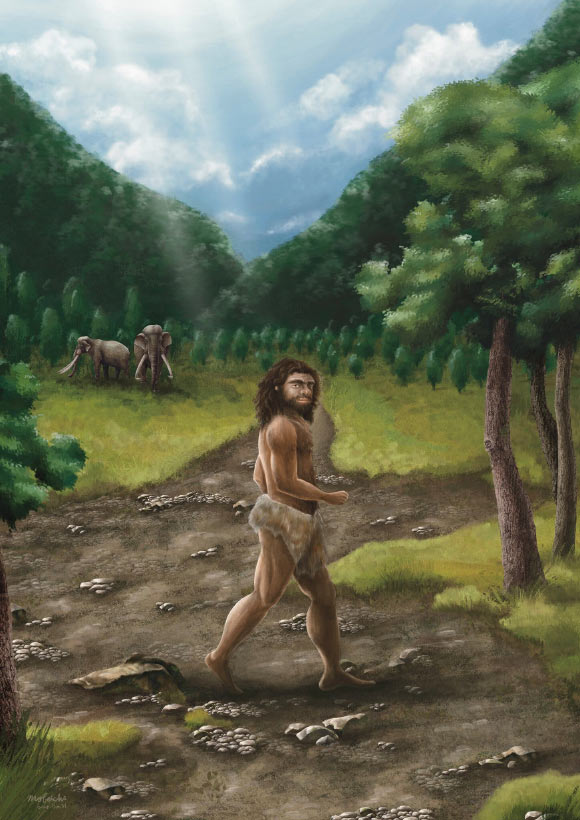

An artist’s concept of a Penghu Denisovan walking under the bright Sun during the Pleistocene of Taiwan. Image credit: Cheng-Han Sun.

“Recent examinations and reinterpretations of fossil remains, coupled with the deployment of molecular methodologies and advanced dating techniques, have unveiled surprising diversity within archaic hominin populations in East Asia during the Middle to Late Pleistocene epoch, preceding the advent of anatomically modern humans,” stated Dr. Takumi Tsutaya, a researcher affiliated with the University of Copenhagen and the Graduate University for Advanced Studies (SOKENDAI), alongside his collaborators.

“The definitive identification of Denisovans represents a pivotal example of such a breakthrough.”

“The recognition of Denisovans as a distinct hominin lineage, separate from Neanderthals and contemporary humans, was achieved through the examination of DNA extracted from fragmented bone and tooth remains unearthed from Denisova Cave, situated in the Altai Mountains of Siberia.”

“Their nuclear genome suggests that Denisovans constitute their own distinct branch, positioned as a sister group to Neanderthals, with a computed genomic divergence between these two lineages occurring upwards of 400,000 years in the past.”

“Furthermore, genetic evidence points to interbreeding events between Denisovans, modern humans, and Neanderthals.”

“Investigations into introgressed Denisovan DNA found within modern human populations imply the existence of multiple, genomically differentiated Denisovan groups, which were once geographically dispersed across a vast expanse of continental East Asia and potentially some regions of island Southeast Asia.”

“However, beyond the confines of Denisova Cave, concrete molecular documentation of Denisovans has thus far been limited to a solitary site on the Tibetan Plateau.”

“At Baishiya Karst Cave in Xiahe, a mandible and a rib have been classified as Denisovan based on their protein sequences.”

Designated Penghu 1, this newly identified Denisovan fossil was recovered in the 2000s. Its acquisition resulted from dredging operations connected to commercial fishing, occurring on the seabed (at depths ranging from 60 to 120 meters) approximately 25 kilometers off Taiwan’s western coastline.

This geographical locale is situated 4,000 kilometers southeast of Denisova Cave and 2,000 kilometers southeast of Baishiya Karst Cave.

During periods of diminished sea levels in the Pleistocene epoch, this region was integrated into the Asian mainland.

“The Penghu 1 fossil is dated to be younger than 450,000 years old, with its most probable age falling within the 10,000 to 70,000-year range, or alternatively between 130,000 and 190,000 years, according to analyses of trace element content, biostratigraphic indicators, and historical sea-level fluctuations,” the research team reported.

“Direct uranium dating of the Penghu 1 specimen proved unsuccessful due to interference from uranium present in the seawater.”

Employing ancient proteomic analysis, Dr. Tsutaya and his associates successfully extracted proteins from both the bone and dental enamel of the fossil. This process yielded 4,241 amino acid residues, among which two exhibited Denisovan-specific protein variations.

These particular variations are infrequently observed in contemporary human populations but demonstrate a higher prevalence in geographical areas associated with Denisovan genetic admixture.

Moreover, a morphological examination of the Penghu 1 remains reveals a sturdy jaw structure characterized by substantial molars and distinctive root formations. These features are consistent with traits observed in the Tibetan Denisovan specimen, suggesting these characteristics were representative of the Denisovan lineage and potentially indicative of sex-specific attributes.

“It is now evident that two distinct hominin groups – Neanderthals, characterized by smaller teeth and tall yet slender mandibles, and Denisovans, possessing larger teeth and low, robust mandibles (potentially representing a population trait or a male characteristic) – coexisted in Eurasia during the late Middle to early Late Pleistocene periods,” the scientists concluded.

“Given that the latter set of morphological features are either scarce or absent in fossils from the late Early to early Middle Pleistocene periods across Africa and Eurasia, they are not interpreted as primitive ancestral traits, contrary to previous hypotheses. Instead, they likely developed or were amplified within the Denisovan clade subsequent to their genetic divergence from Neanderthals over 400,000 years ago.”

“Recent findings from island Southeast Asia (involving Homo floresiensis and Homo luzonensis) and South Africa (Homo naledi) underscore the diverse evolutionary trajectories within the genus Homo, presenting a contrast to the lineage that ultimately led to Homo sapiens.”

“The dentognathic morphology observed in Denisovans can be construed as another instance of such unique evolutionary development within our genus.”

The findings were officially published today in the esteemed journal Science.

_____

Takumi Tsutaya et al. 2025. A male Denisovan mandible from Pleistocene Taiwan. Science 388 (6743): 176-180; doi: 10.1126/science.ads3888