The capacity for distal gene regulation—the intricate process of influencing genetic expression from remote DNA segments spanning tens of thousands of nucleotides—emerged at the nascent stages of animal evolution, approximately 650 to 700 million years ago during the Cryogenian period. This predates prior estimations by roughly 150 million years.

Illustration of a DNA molecule. Image credit: Christoph Bock, Max Planck Institute for Informatics / CC BY-SA 3.0.

Remote gene control is facilitated by the sophisticated looping of DNA and associated proteins.

This architectural arrangement enables DNA sequences situated far from a gene’s transcriptional start site to modulate its activity.

This advanced regulatory mechanism likely played a pivotal role in the development of specialized cell types and tissues in the earliest multicellular organisms, obviating the necessity for novel gene creation.

It is hypothesized that this fundamental innovation originated within an aquatic organism, representing the common progenitor of all extant animal species.

This ancestral creature attained the ability to manipulate DNA folding in a controlled fashion, thereby establishing three-dimensional loops that facilitated direct physical contact between disparate DNA segments.

“This organism possessed the remarkable capability to adapt its genetic repertoire for diverse functions, akin to a multi-tool, which empowered it to refine and explore novel survival strategies,” stated Dr. Iana Kim, a postdoctoral researcher affiliated with the Centre for Genomic Regulation and the Centre Nacional d’Anàlisis Genòmica.

“The profound antiquity of this regulatory complexity was unanticipated.”

The discovery by Dr. Kim and her research associates was the result of an extensive examination of the genomic data from numerous phylogenetically ancient animal lineages, including ctenophores such as the sea walnut (Mnemiopsis leidyi), placozoans, cnidarians, and sponges.

Additionally, studies were conducted on unicellular organisms that, while not classified as animals, share a recent common ancestor with them.

“Investigating the biology of unusual marine fauna can yield significant novel insights,” commented Professor Arnau Sebe-Pedrós, a researcher at the Centre for Genomic Regulation.

“While our prior investigations were confined to comparative genomic sequencing, contemporary methodologies now permit an analysis of the gene regulatory mechanisms governing genome function across various species.”

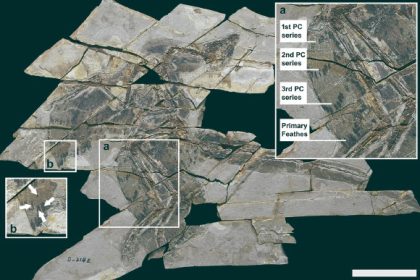

An atypically large individual of Mnemiopsis leidyi with two aboral ends and two apical organs. Image credit: Jokura et al., doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.07.084.

The research team employed the Micro-C technique to precisely map the three-dimensional folding patterns of DNA within the cellular structures of eleven distinct species under investigation. For context, the DNA contained within a single human cell nucleus measures approximately 2 meters in length.

The scientists meticulously analyzed a dataset comprising 10 billion DNA sequencing fragments to construct detailed three-dimensional genomic maps for each species.

While no evidence of distal regulation was detected in the animal relatives that are single-celled, early-branching animal groups such as ctenophores, placozoans, and cnidarians exhibited a significant abundance of DNA loops.

The sea walnut, in isolation, demonstrated over four thousand genome-wide loops.

This finding is particularly noteworthy considering its genome comprises approximately only 200 million DNA letters.

In contrast, the human genome contains 3.1 billion letters, and human cells can possess tens of thousands of such loops.

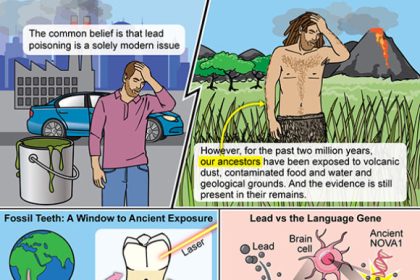

Previously, it was believed that distal regulation first appeared in the last common ancestor of bilaterians, a diverse assemblage of animal phyla that arose on Earth approximately 500 million years ago.

However, ctenophores are phylogenetically derived from organisms that diverged from other animal lineages around 650 to 700 million years ago.

“While the phylogenetic positioning of ctenophores relative to sponges within the tree of life remains a subject of ongoing debate in evolutionary biology, this study unequivocally demonstrates that distal regulation emerged at least 150 million years prior to previously established timelines,” the study authors reported.

A treatise detailing these discoveries has been officially published in the esteemed journal Nature.

_____

I.V. Kim et al. Chromatin loops are an ancestral hallmark of the animal regulatory genome. Nature, published online May 7, 2025; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-08960-w