Recent investigations have revealed the existence of a modest, geographically isolated populace of common hippos (Hippopotamus amphibius) within the Upper Rhine Graben of southwestern Germany during the mid-Weichselian epoch, a period extending from approximately 47,000 to 31,000 years ago.

Radiocarbon dating has established the presence of common hippos (Hippopotamus amphibius) in the Upper Rhine Graben, Germany, during the middle Weichselian period. Image credit: Gemini AI.

Europe was colonized by hippos originating from Africa through several migratory waves, likely involving various species within the genus Hippopotamus, including the common hippo, which is presently indigenous solely to sub-Saharan Africa.

During their widest geographical reach across Europe, hippos were found from the British Isles to the northwest, extending to the Iberian and Italian peninsulas in the south.

Their appearance in the fossil record typically signifies the presence of temperate climatic conditions, characterized by abundant vegetation and accessible bodies of water.

However, their precise origins, their evolutionary relationship to contemporary African common hippos, and the exact timeframe of their disappearance from central Europe remain subjects of ongoing inquiry.

“Previously, the prevailing assumption was that common hippos had vanished from central Europe around 115,000 years ago, coinciding with the conclusion of the last interglacial period,” stated Professor Wilfried Rosendahl, co-senior author and general director of the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen Mannheim.

“Our findings indicate that hippos inhabited the Upper Rhine Graben in southwestern Germany during an interval roughly between 47,000 and 31,000 years ago.”

In conducting their research, Professor Rosendahl and his associates meticulously examined nineteen hippo specimens sourced from fossil sites within the Upper Rhine Graben.

“The Upper Rhine Graben serves as a significant repository of continental climate history,” commented Dr. Ronny Friedrich, a research associate at the Curt-Engelhorn-Zentrum Archäometrie and a co-author of the study.

“Fossilized animal bones that have endured for millennia within gravel and sand deposits offer invaluable data for scientific exploration.”

He further remarked, “The remarkable state of preservation of these bones is truly astonishing.”

“It was feasible to extract viable samples for analysis from numerous skeletal remains—a feat not always achievable given such extensive periods.”

Subsequent analysis of ancient DNA by the research team confirmed that the hippos of the European Ice Age were genetically closely related to modern African hippos, belonging to the same species.

Radiocarbon dating provided empirical support for their existence during a comparatively milder climatic phase within the middle Weichselian period.

An additional genome-wide assessment revealed a notably low degree of genetic diversity, suggesting that the hippo population in the Upper Rhine Graben was both small and geographically isolated.

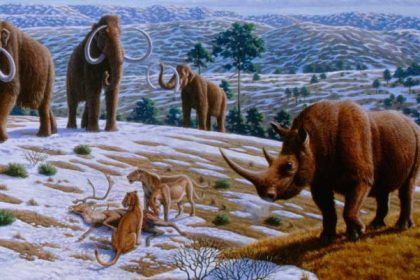

These findings, corroborated by further paleontological evidence, indicate that thermophilic hippos coexisted with species adapted to frigid environments, such as mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses, within the same temporal framework.

“The study’s outcomes challenge the long-held belief that hippos disappeared from central Europe at the close of the last interglacial period,” noted Dr. Patrick Arnold, the lead author of the study and a researcher at the University of Potsdam.

“Consequently, it is imperative that we revisit and re-evaluate other continental European hippo fossils that have traditionally been classified as belonging to the last interglacial period.”

Professor Rosendahl elaborated, “The present investigation offers crucial new perspectives that compellingly demonstrate the Ice Age was not uniform across all regions, but rather a complex mosaic of local characteristics, akin to assembling a puzzle.”

He added, “It would be highly beneficial and significant to extend our examination to other heat-loving animal species that have, until now, been solely attributed to the last interglacial period.”

The findings were officially published on October 8, 2025, in the esteemed journal Current Biology.

_____

Patrick Arnold et al. Ancient DNA and dating evidence for the dispersal of hippos into central Europe during the last glacial. Current Biology, published online October 8, 2025; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.09.035