A recent publication this month in the esteemed journal iScience features a comprehensive, multidisciplinary examination of stone and bone projectile points attributed to Homo sapiens during the early Upper Paleolithic period, spanning from 40,000 to 35,000 years ago. Researchers affiliated with the University of Tübingen and other institutions employed a combination of experimental ballistics, meticulous measurements, and detailed use-wear analyses. Their conclusions suggest that certain ancient artifacts found are consistent with propulsion via a bow and arrow, rather than exclusively being associated with hand-thrown spears or darts launched by spear-throwers.

Indigenous populations may have employed the bow and arrow alongside spear-throwers in the early Upper Paleolithic era. Image attribution: sjs.org / CC BY-SA 3.0.

For a considerable duration, the prevailing archaeological consensus posited a linear evolutionary trajectory for weapon technologies, commencing with handheld spears, progressing to spear-throwers, and culminating in the advent of the bow and arrow.

However, Keiko Kitagawa, a researcher from the University of Tübingen, along with her collaborators, contend that technological advancements did not follow a straightforward sequential pattern.

The scientists noted, “Direct archaeological evidence pertaining to hunting weaponry is scarce.”

“The spectrum of prehistoric hunting implements encompasses handheld thrusting spears, effective for ambushing prey at close range, to projectile systems involving a spear propelled by a spear-thrower, and subsequently, arrows launched from a bow, all designed for medium to long-distance engagements.”

“The earliest manifestations of such implements, specifically wooden spears and throwing sticks, have been dated to the period between 337,000 and 300,000 years ago within Europe.”

“Artifacts crafted from antler, interpreted as hooks for spear-throwers, begin to be documented in contexts associated with the Upper Solutrean period (approximately 24,500 to 21,000 years ago). Their prevalence increases notably in the Magdalenian period (beginning around 21,000 years ago) across Southwestern France, with nearly one hundred examples identified.”

“Concurrently, evidence for bow and arrow technology has only been unearthed in exceptionally well-preserved archaeological sites dating to the Final Paleolithic era in Mannheim-Vogelstang and Stellmoor, Germany, approximately 12,000 years ago, and at the Early Mesolithic site of Lilla Loshults Mosse in Sweden (circa 8,500 years ago). This positions bow and arrow technology as considerably more recent compared to other projectile weapon systems.”

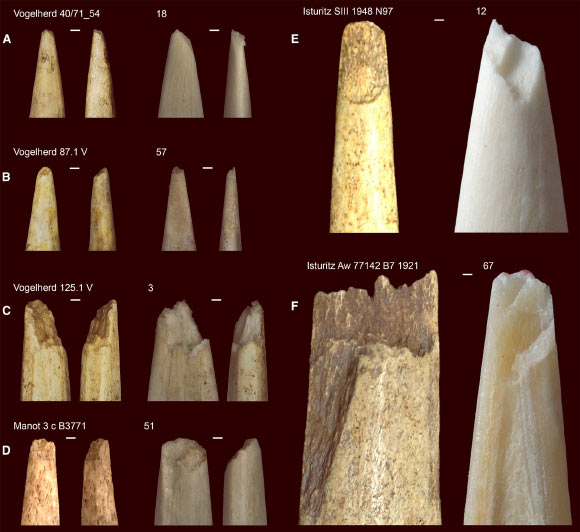

Illustrations from Aurignacian archaeological locations, including Vogelherd in Germany, Isturitz in France, and Manot in Israel, are juxtaposed with experimental samples. Image credit: Kitagawa et al., doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.114270.

In their published work, the authors posit that early modern humans likely engaged in experimentation with various projectile systems concurrently or during overlapping temporal phases, indicating diverse adaptive strategies tailored to different ecological environments and prey species.

The critical evidence is derived from the distinctive patterns of fracture and wear observed on these ancient projectile points following their use.

Through controlled experiments where stone and bone points were affixed to shafts and propelled, the resultant breakage and micro-damage patterns exhibited by certain specimens precisely matched expectations for projectiles launched from a bow, rather than those solely propelled by hand-thrown spears or darts.

“Our investigation focuses on osseous projectile implements from the Upper Paleolithic, specifically split- and massive-based points fashioned from antler and bone. These were predominantly discovered in Aurignacian contexts across Europe and the Levant, dating between 40,000 and 33,000 years ago,” the researchers stated.

“Our objective is to ascertain whether the type of weapon onto which these Aurignacian osseous projectile points were mounted can be determined through an analysis of their use-wear characteristics and morphometric attributes.”

These findings align with prior archaeological research that has presented evidence of bow and arrow utilization in Africa as far back as approximately 54,000 years ago. This timeframe is earlier than previously believed and predates certain aspects of the European archaeological record.

Crucially, the research team clarifies that they are not asserting that Homo sapiens independently invented the bow in all locations simultaneously, nor do they propose that bows constituted the sole weapon employed.

Rather, the study suggests the existence of a diverse technological arsenal during the initial stages of human dispersal into novel territories.

“Our research, in part, underscores the inherent complexity in reconstructing projectile technologies, as these were frequently manufactured from perishable materials,” the investigators concluded.

“While it is not feasible to account for every variable influencing the physical properties of armatures and the resulting damage, future experimental programs designed to address the multifaceted nature of projectiles could potentially illuminate further insights into one of the fundamental pillars of hunter-gatherer economies.”

_____

Keiko Kitagawa et al. Homo sapiens could have hunted with bow and arrow from the onset of the early Upper Palaeolithic in Eurasia. iScience, published online December 18, 2025; doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.114270