Canids, ancestral to domestic dogs, stand as the solitary large carnivorous species to have undergone human-driven domestication. The precise mechanisms of this process, however, remain ambiguous. Specifically, it is uncertain whether this evolution occurred through direct human intervention with wild wolf populations or if these canids gradually adapted to human ecological niches. Recent archaeological investigations within the Stora Förvar cave, situated on the Swedish island of Stora Karlsö in the Baltic Sea, have brought to light the skeletal remains of two individuals exhibiting gray wolf genetic heritage. This particular island, a modest landmass measuring 2.5 km², is devoid of indigenous terrestrial mammal populations, a characteristic it shares with the adjacent island of Gotland. Consequently, any fauna present on this island must have been introduced by human agency.

Canadian Eskimo dogs by John James Audubon and John Bachman.

“The unearthing of these wolves on an isolated island was entirely unanticipated,” stated Dr. Linus Girdland-Flink, a researcher affiliated with the University of Aberdeen.

“Not only did their genetic lineage prove indistinguishable from contemporary Eurasian wolves, but their presence suggested cohabitation with humans, consumption of human-provided sustenance, and an environment accessible only by maritime transport.”

“This presents a multifaceted perspective on the historical interplay between humans and wolves.”

Subsequent genomic sequencing of the two canid specimens recovered from the Stora Förvar cave definitively identified them as wolves, not domestic dogs.

Nevertheless, certain characteristics observable in these remains are typically indicative of a life lived in close proximity to human settlements.

Isotopic analysis of their skeletal structures revealed a dietary composition heavily reliant on marine resources, such as seals and fish. This aligns with the foodstuffs consumed by the human inhabitants of the island, strongly implying that these wolves were provisioned.

Moreover, the island wolves were found to be of smaller stature compared to their mainland counterparts. One individual, in particular, displayed markers of diminished genetic diversity, a phenomenon commonly observed in populations experiencing isolation or subjected to selective breeding protocols.

These discoveries impinge upon established understandings of human-wolf interactions and the trajectory of canine domestication.

While the exact nature of their management remains elusive – whether through taming, confinement, or other forms of control – their habitation within a human-occupied, isolated setting unequivocally points to sustained and deliberate engagement.

“The revelation that it was indeed a wolf, rather than a dog, came as a profound surprise,” commented Dr. Pontus Skoglund, a researcher at the Francis Crick Institute.

“This represents a compelling case study that suggests the potential for humans, in specific environmental contexts, to maintain wolves within their settlements, deriving some form of benefit from such cohabitation.”

“The genetic data are exceptionally intriguing,” remarked Dr. Anders Bergström, a researcher from the University of East Anglia.

“We determined that the wolf possessing the most complete genomic sequence exhibited reduced genetic diversity, lower than any previously analyzed ancient wolf specimen.”

“This pattern is analogous to what is observed in populations that are isolated, have experienced bottlenecks, or in organisms undergoing domestication.”

“Although we cannot definitively exclude the possibility of natural causes for this low genetic diversity, it strongly suggests that humans were actively interacting with and managing these wolves in ways that were not previously contemplated.”

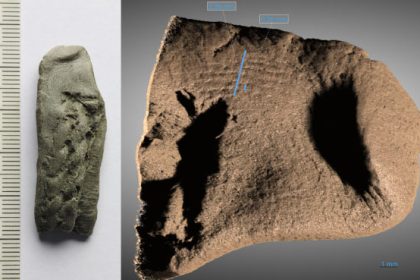

One of the wolf specimens, radiocarbon-dated to the Bronze Age, also exhibited significant pathological changes in a limb bone, which would have likely restricted its mobility.

This finding implies that the individual may have received care or was capable of subsisting in an environment where the pursuit of large prey was not a necessity.

“The confluence of these various data streams has illuminated novel and highly unexpected perspectives on human-animal interactions during the Stone and Bronze Ages, particularly concerning wolves and, by extension, dogs,” stated Professor Jan Storå of Stockholm University.

“The research indicates that prehistoric human-wolf relationships were more varied than previously posited, extending beyond mere hunting or avoidance to encompass intricate associations. In this specific instance, these interactions mirror emergent facets of domestication without culminating in the ancestral lineage of modern dogs.”

A research paper detailing these findings was published on November 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____

Linus Girdland-Flink et al. 2025. Gray wolves in an anthropogenic context on a small island in prehistoric Scandinavia. PNAS 122 (48): e2421759122; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2421759122