Elevated blood glucose excursions following meals may represent a contributing element to the susceptibility of Alzheimer’s disease, according to novel research that enhances our comprehension of the interconnections between diabetes, impaired insulin sensitivity, and cognitive decline.

Prior investigations have indicated a potential nexus between diabetes and dementia in certain scenarios. However, the precise causal relationship and the underlying biological pathways involved remain subjects of ongoing scientific scrutiny.

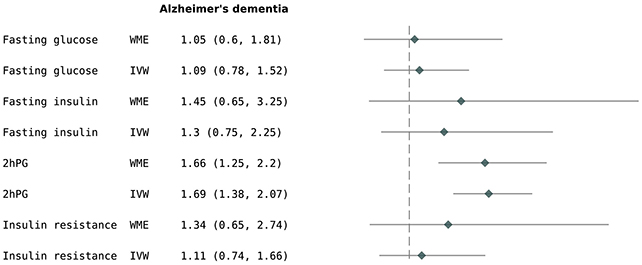

In this latest endeavor, investigators from the United Kingdom conducted an extensive analysis of a substantial genetic repository encompassing 357,883 individuals. Their findings revealed that individuals exhibiting relatively higher postprandial (after-meal) glucose concentrations demonstrated a 69 percent greater propensity to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

“This discovery holds the potential to inform future preventative initiatives, emphasizing the critical importance of glycemic control not only on an ongoing basis but specifically in the post-meal period,” commented Andrew Mason, an epidemiologist affiliated with the University of Liverpool.

The research team employed a methodology known as Mendelian Randomization (MR) for their data analysis. Rather than directly quantifying post-meal blood sugar levels, they identified individuals possessing genetic markers predisposed to postprandial glucose surges.

By focusing on innate genetic predispositions, this approach effectively mitigates the confounding influence of environmental variables and co-existing health conditions, thereby facilitating a more robust determination of causality.

While a robust association was identified between postprandial hyperglycemia and Alzheimer’s, no correlative link was established for conventional glucose or insulin levels, nor for insulin resistance, in relation to either Alzheimer’s or dementia in its general form.

Furthermore, neuroimaging studies conducted on a cohort subset revealed no discernible relationship between glycemic or insulin-related traits and alterations in brain or hippocampal volume, or increased white matter pathology. This suggests that a more nuanced mechanism likely underlies the connection between post-meal glucose spikes and Alzheimer’s disease.

“Prior epidemiological and MR investigations have suggested that 2-hour post-load glucose serves as a glycaemic indicator strongly predictive of adverse cardiovascular outcomes,” state the study’s authors in their published work.

“Our findings propose that the genetic susceptibility to this marker of postprandial glycemia is also implicated in an augmented risk profile for Alzheimer’s disease.”

The precise mechanisms by which post-meal glucose elevations elevate dementia risk remain elusive. However, it is established that cerebral function, akin to that of the entire organism, is dependent on glucose availability. It is plausible that a form of neuroinflammation or oxidative stress is induced within brain cells following meals, potentially offering avenues for future therapeutic interventions or preventative strategies against dementia.

Nevertheless, a significant limitation of this research warrants acknowledgment: the research team was unable to reproduce these findings in an earlier genetic cohort comprising 111,326 individuals. The investigators hypothesize that disparities in participant selection criteria may account for this discrepancy.

The primary UK Biobank dataset utilized in this study tends to overrepresent healthier individuals and those from higher socioeconomic strata, and exclusively draws from participants of White British ancestry. Consequently, further investigations are imperative to validate these hypotheses across more diverse demographic groups.

“Our initial priority is to reproduce these findings in alternative populations and ancestries to corroborate the association and gain a more profound understanding of the underlying biological processes,” articulated Vicky Garfield, a genetic epidemiologist also at the University of Liverpool.

“Should these results be substantiated, this study could illuminate novel pathways for mitigating dementia risk, particularly among individuals diagnosed with diabetes.”