While definitive proof of past microbial presence on Ceres remains elusive, a recent investigation’s outcomes lend credence to hypotheses suggesting this dwarf planet once harbored conditions conducive to supporting rudimentary, single-celled organisms.

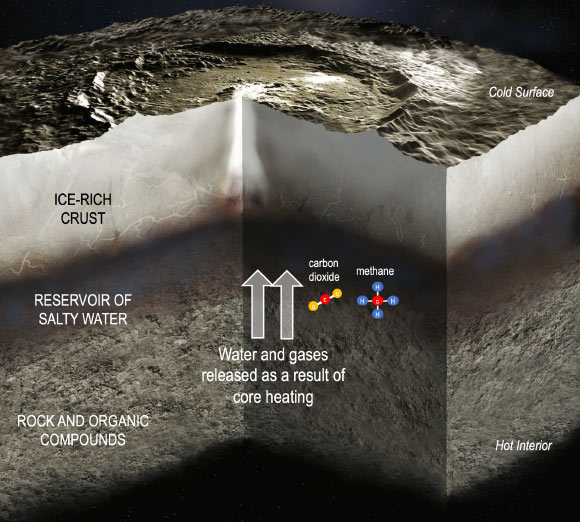

An artistic rendering illustrating Ceres’ internal structure, depicting the upward movement of water and gases from its rocky nucleus into a saline liquid reservoir. Notably, carbon dioxide and methane are identified as key molecules imparting chemical energy beneath the celestial body’s crust. Image courtesy of NASA / JPL-Caltech.

Data acquired by NASA’s Dawn mission had previously indicated that the luminous, reflective patches observable on Ceres’ surface are predominantly composed of mineral deposits derived from subsurface liquid that ascended through the planet’s interior.

Subsequent evaluations conducted in 2020 pinpointed the origin of this liquid as an extensive subterranean reservoir of brine, essentially highly saline water.

Further discoveries from the Dawn mission also unveiled the presence of organic compounds in the form of carbon molecules on Ceres – a crucial, though not solitary, prerequisite for the sustenance of microbial life.

The co-existence of water and carbon molecules represents two fundamental elements in the assessment of the dwarf planet’s potential for habitability.

The latest research adds a third vital component: a persistent source of chemical energy within Ceres’ ancient past, which could have facilitated the survival of microorganisms.

This revelation does not assert the existence of life on Ceres but rather suggests that sustenance would have been available had any life forms emerged there.

In a newly presented study, lead investigator Dr. Sam Courville, affiliated with Arizona State University and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, devised thermal and chemical simulations to model the historical temperature fluctuations and composition of Ceres’ interior.

Their findings indicate that approximately 2.5 billion years ago, Ceres’ subsurface ocean likely received a continuous influx of heated water carrying dissolved gases, originating from metamorphosed rocks within its stony core.

This geothermal heat was generated by the radioactive decay of elements present in the dwarf planet’s rocky interior during its formative stages – a geological process presumed to be prevalent across our Solar System.

“On Earth, the interaction of subterranean hot water with oceanic environments frequently creates an abundant source of chemical energy for microbial communities,” Dr. Courville explained.

“Therefore, the confirmation of hydrothermal fluid influx into Ceres’ ocean in its past would carry significant implications.”

The Ceres observed today is considered unlikely to be capable of supporting life. Its current state is characterized by lower temperatures, a greater prevalence of ice, and reduced quantities of liquid water compared to its historical condition.

Presently, the internal heat generated by radioactive decay within Ceres is insufficient to prevent its water from freezing, and the remaining liquid has evolved into a highly concentrated brine.

The period most propitious for habitability on Ceres is estimated to have occurred between half a billion and 2 billion years following its formation (corresponding to roughly 2.5 to 4 billion years ago), when its rocky core attained peak thermal activity.

It was during this epoch that elevated temperatures would have facilitated the introduction of warm fluids into Ceres’ subterranean water bodies.

Furthermore, the dwarf planet lacks the benefit of ongoing internal heating derived from tidal forces exerted by a massive planetary companion, a phenomenon observed in moons such as Saturn’s Enceladus and Jupiter’s Europa.

Consequently, Ceres’ optimal potential for habitability-related energy provision was confined to its distant past.

“Since that period, Ceres’ ocean has likely transformed into a frigid, concentrated saline solution with diminished energy sources, rendering it less hospitable in the present era,” the researchers concluded.

A research publication detailing these findings was disseminated today in the esteemed journal Science Advances.

_____

Samuel W. Courville et al. 2025. Core metamorphism controls the dynamic habitability of mid-sized ocean worlds – The case of Ceres. Science Advances 11 (34); doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adt3283