A significant new scientific investigation has been released, providing enhanced clarity regarding the magnitude of future global temperature increases anticipated.

This research, spearheaded by my colleague, climate scientist Steven Sherwood of the University of New South Wales in Australia, involved numerous international climate experts. Consequently, I engaged him in a discussion to ascertain its implications for us and for the future.

It is an established scientific principle that the Earth’s climate undergoes warming as atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, ascend. Analysis of NASA’s temperature data reveals that since the 1950s, the planet has experienced an approximate warming of 0.8 °C up to the most recent decade.

Furthermore, it is virtually certain that anthropogenic activities are the principal driver of this recent climatic warming (a topic I explore in depth in this article). However, projections for future warming and the methodologies employed by climate scientists for such predictions warrant closer examination.

Key Uncertainties: Energy, Economics, and Geopolitics

The extent of future warming remains a subject of considerable uncertainty, largely attributable to a primary unknown: the volume of carbon emissions humanity will generate in the ensuing decades. Such emissions are intrinsically linked to socio-political and economic frameworks, factors that are exceedingly difficult to forecast even for the short term, let alone over many years!

In response, scientists have developed sophisticated earth-system models to project future climate trajectories. These models are calibrated using a spectrum of prospective carbon pollution scenarios, ranging from the extreme of exhausting all coal reserves to the radical measure of immediately ceasing all coal-fired power generation.

However, another critical factor contributing to predictive uncertainty is the Earth’s inherent sensitivity to elevated carbon dioxide levels.

This phenomenon is termed “equilibrium climate sensitivity” by scientists. It quantizes the anticipated temperature rise corresponding to a sustained doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations.

Historically, the equilibrium climate sensitivity has been estimated within a probable range of 1.5 to 4.5 °C. This signifies that at such a juncture when atmospheric carbon dioxide reaches 560 parts per million (ppm), the Earth’s temperature is projected to increase by 1.5 to 4.5 °C – a range that has persistently lacked definitive resolution.

The latest research represents the most comprehensive appraisal of all available empirical data to date. It establishes the most probable range as 2.6 to 3.9 °C. Nevertheless, Professor Sherwood points out that achieving this “equilibrium temperature” would necessitate hundreds of years:

“It requires a substantial duration for the Earth’s system to fully adapt to shifts in incoming energy flows, a process spanning centuries. However, the majority of the temperature elevation occurs within approximately a decade of the initial change. We posit that the actual warming experienced over the current century (contingent on an emission scenario) is closely correlated with the equilibrium warming magnitude, implying that knowledge of one provides a reasonable approximation of the other.”

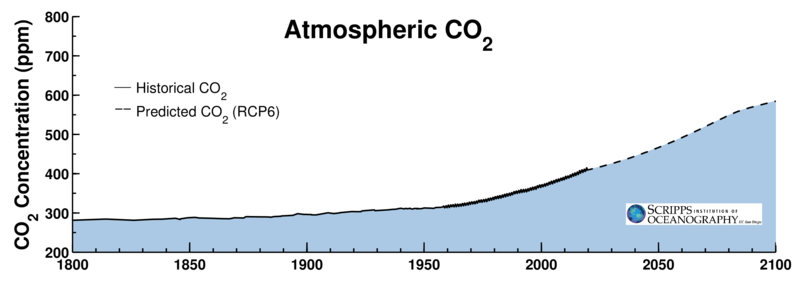

Presently, what is the approximate progress towards a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations? We are nearly halfway there. Pre-industrial levels (circa AD 1880) stood at approximately 280 ppm, whereas current levels are around 413 ppm (as indicated by the terminal point of the solid graphical representation below).

Assuming a gradual increase in concentrations without significant global political intervention, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels could reach 560 ppm, signifying a doubling, by approximately 2070.

Consequently, the recent study suggests that we are presently facing a long-term warming commitment of roughly 1.3 to 2.0 °C. However, other factors will influence this trajectory.

Positive Developments: Extreme Warming Scenarios Are Less Probable

Until recently, scenarios predicting warming of 5 to 6 °C by 2100, which would precipitate catastrophic global repercussions, were not entirely discounted. The encouraging conclusion from this new research, as stated by Professor Sherwood, is that the most severe warming projections are now considered less likely:

By the year 2100, I believe we can largely dismiss the possibility of 5 °C warming, provided the world does not adopt radically unsustainable policies. However, this does not preclude such levels by 2200 if fossil fuel consumption continues unabated towards the end of this century and into the next.

However, the 1.5 °C Target is Out of Reach, and Likely the 2 °C Target as Well…

The most optimistic projection for future emissions involves a dramatic reduction in the global consumption of coal, oil, and gas by 2050.

Even under such a stringent scenario, Professor Sherwood indicates that preventing global warming from exceeding 1.5 °C becomes exceedingly difficult:

The most optimistic future scenario presents an 83 percent probability of remaining below a 2 °C increase, yet only a 33 percent chance of staying under 1.5 °C. Consequently, adhering to the 1.5 °C limit would be extraordinarily challenging, necessitating highly aggressive mitigation measures under this hypothetical scenario.

Given the current emission trends, the most optimistic scenario is not materializing in reality. Therefore, the window for limiting warming to 2 °C is rapidly diminishing, according to Professor Sherwood:

A scenario aligned with current global policy commitments offers less than a 10 percent probability of remaining below 2 °C. Essentially, a substantial enhancement of our efforts and commitments is imperative to establish a viable prospect of achieving the 2 °C objective.

Based on the findings of the new study and the most probable future emission trajectory, the anticipated warming by 2100 is likely to fall within the range of 2 to 3 °C.

Why Should a 2-3°C Increase Matter? It Seems Insignificant…

Imagine yourself situated within the verdant expanse of New York City’s Central Park. If you could journey back 20,000 years, what would confront your gaze as you surveyed Manhattan? Would it be dense forests and tranquil lakes?

In reality, the landscape would bear a striking resemblance to Antarctica during that epoch – with dense woodlands supplanted by a formidable expanse of glacial ice extending across the entirety of New York City and reaching as far north as Canada.

What is the significance of this visualization of the New York City ice sheet? It underscores that during periods of significant glaciation, a mere reduction of approximately 4 °C in average global temperature was sufficient to foster the formation of that immense, kilometer-thick ice sheet over New York.

As a climate scientist, it can be challenging to effectively communicate this point, but even incremental shifts in the Earth’s average temperature can precipitate profound and far-reaching consequences over extended temporal scales.