The latter half of the first millennium CE was a period of profound societal and political upheaval across Central and Eastern Europe. This era of significant change is intrinsically linked to the emergence of Slavic populations, a connection substantiated by historical texts and congruent archaeological findings. Nevertheless, a definitive understanding has remained elusive regarding whether this archaeological phenomenon spread through migration, cultural assimilation (‘Slavicization’), or a confluence of both. Genetic evidence has been notably scarce, largely attributed to the prevalent practice of cremation during the initial stages of Slavic settlement. In a recent scientific endeavor, researchers sequenced the genomes of 555 ancient individuals, incorporating 359 samples dating back to the 7th century CE and originating from contexts associated with Slavic cultures. The resultant data illuminate a substantial population displacement from Eastern Europe between the 6th and 8th centuries, leading to the replacement of over 80% of the indigenous genetic makeup in regions of Eastern Germany, Poland, and Croatia.

Seal of Yaroslav the Wise, the Grand Prince of Kyiv from 1019 until 1054 and the father of Anna Yaroslavna, the Queen of France. Image credit: Sheremetievs Museum.

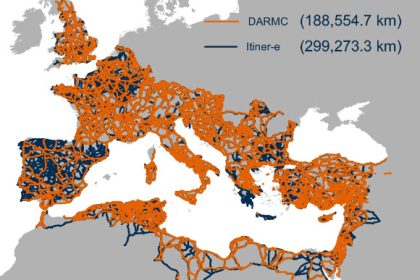

The designation ‘Slavs’ first emerged as an ethnonym during the 6th century, documented in Constantinople and subsequently in Western records.

Historical accounts initially situated these groups north of the Lower Danube, with later attestations placing them in the Carpathian Basin, the Balkans, and the Eastern Alps.

A considerable number of these populations fell under the dominion of the Avar steppe empire, which spanned the Middle Danube region from 567 CE until approximately 800 CE.

The 7th century witnessed the documented presence of Slavic peoples across a significant portion of East-Central and Southeastern Europe.

In areas inhabited by Slavs, pre-existing Roman, Germanic, and other non-Slavic infrastructures were typically supplanted by simpler modes of living. Archaeologically, this is characterized by diminutive settlements featuring pit dwellings, cremation burials, handmade, unadorned pottery, and modest material culture with minimal metal usage, collectively recognized as the Prague-Korchak assemblage.

More sophisticated societal structures and regional governance evolved later, particularly in areas of interaction with Byzantium and with the Christian West.

The European Transformation Driven by Slavic Migrations

The inaugural comprehensive analysis of ancient DNA from medieval Slavic populations reveals that the expansion of the Slavs was fundamentally a narrative of demographic movement.

Their genetic markers indicate an origin in the territory extending from southern Belarus to central Ukraine, a geographical scope aligning with numerous linguistic and archaeological reconstructions.

“While direct evidence from the core regions of early Slavic settlement remains scarce, our genetic findings furnish the initial concrete indications of Slavic ancestry formation, suggesting a likely origin somewhere between the Dniester and Don rivers,” stated Dr. Joscha Gretzinger, a geneticist affiliated with the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

In this investigative study, Dr. Gretzinger and his collaborators acquired genome-wide data from 555 distinct ancient individuals across 26 diverse sites in Central and Eastern Europe. This dataset, when combined with previously disseminated information, established a dense sampling transect covering three key regions: (i) the Elbe-Saale Region in Eastern Germany, serving as the primary focus of the inquiry; (ii) the Northwestern Balkans; and (iii) Poland and Northwestern Ukraine.

The new genetic evidence demonstrates that commencing in the 6th century CE, extensive migratory movements disseminated Eastern European ancestry across vast expanses of Central and Eastern Europe, precipitating a near-total alteration of the genetic composition in areas such as Eastern Germany and Poland.

However, this expansion did not conform to a model of military conquest or empire-building. Rather than deploying formidable armies and rigid hierarchical systems, the migrating groups established their new societies based on adaptable communal structures, frequently organized around extended family units and patrilineal kinship affiliations.

Furthermore, this societal framework was not uniform across all geographical areas.

Within Eastern Germany, the demographic shift was particularly striking: extensive, multi-generational family units constituted the societal bedrock, with kinship networks proving to be more expansive and structured than the smaller, nuclear family units observed during the preceding Migration Period.

In contrast, in regions such as Croatia, the arrival of Eastern European groups introduced considerably less disruption to the existing social topologies.

In these locales, social organization frequently retained numerous characteristics of earlier epochs, leading to the formation of communities where novel and established traditions intermingled or coexisted.

This regional variability in social structure underscores the fact that the dissemination of Slavic groups was not a standardized process but rather a dynamic transformation that adapted to prevailing local circumstances and historical trajectories.

“Rather than a single people migrating as a unified entity, the Slavic expansion was not a monolithic event but a mosaic of distinct groups, each adapting and assimilating in its unique manner — suggesting there was never a singular ‘Slavic’ identity, but rather a multitude of them,” articulated Dr. Zuzana Hofmanová, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and Masaryk University.

Historical overview of Slavs in Europe: the timeline lists major historical events associated with the Slavs in Central Europe; the map features schematized historical attestations for the appearance of Slavs (Sklavenoi – Slavi – Winedi); Italic numbers indicate the date of the attested event, with the respective report date in brackets. Image credit: Gretzinger et al., doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09437-6.

Eastern Germany

Specifically within Eastern Germany, the genetic data present a particularly compelling narrative.

Following the dissolution of the Thuringian kingdom, an estimated 85% of the ancestry in this region can be attributed to new arrivals from the East.

This signifies a departure from the earlier Migration Period, during which the populace was characterized by a diverse cosmopolitan mix, as exemplified by the archaeological site of Brücken.

With the expansion of Slavic populations, this prior diversity yielded to a demographic profile nearly identical to that of contemporary Slavic-speaking groups in Eastern Europe.

These newly established communities organized themselves around extensive family structures and patrilineal lineage systems, with women of marriageable age typically relocating from their natal villages to join new households.

Notably, the genetic legacy of these early Eastern European settlers persists today among the Sorbs, a Slavic-speaking minority residing in Eastern Germany.

Despite centuries of surrounding cultural and linguistic assimilation, the Sorbs have maintained a genetic profile closely aligned with the early medieval Slavic populations that settled the region over a millennium ago.

Poland

In Poland, this research challenges previous notions of long-standing population continuity.

Genetic findings indicate that beginning in the 6th and 7th centuries CE, the region’s prior inhabitants—descendants of populations with strong connections to Northern Europe, particularly Scandinavia—were virtually entirely supplanted by newcomers from the East, who are closely related to modern Poles, Ukrainians, and Belarusians.

While the demographic shift was substantial, the genetic evidence also reveals subtle indications of admixture with the indigenous populations.

These discoveries emphasize both the magnitude of population change and the intricate dynamics that shaped the foundational roots of the present-day Central and Eastern European linguistic landscape.

Croatia

The Northern Balkans present a distinct pattern compared to the northern immigration zones, illustrating a history marked by both transformation and persistence.

Ancient DNA extracted from Croatia and adjacent areas indicates a considerable influx of ancestry associated with Eastern Europe, yet not a complete genetic replacement.

Instead, Eastern European migrants integrated with the diverse local populations of the region, leading to the formation of novel, hybrid communities.

Genetic analyses suggest that in contemporary Balkan populations, the proportion of this incoming Eastern European ancestry varies significantly but often constitutes approximately half or even less of the modern gene pool, underscoring the region’s complex demographic history.

In this context, Slavic migration was not a forceful conquest but rather a protracted process of intermarriage and adaptation, resulting in the cultural, linguistic, and genetic diversity that continues to characterize the Balkan Peninsula today.

A New Epoch in European History

Where early Slavic groups are predominantly identified in the archaeological and historical records, their genetic imprints align: a shared ancestral origin, albeit with regional variations shaped by the extent of assimilation with local populations.

In the northern territories, earlier Germanic peoples had largely migrated away, creating space for Slavic settlement.

In the southern regions, the Eastern European newcomers merged with established indigenous communities.

This mosaic-like process accounts for the remarkable diversity observed in the cultures, languages, and even the genetics of contemporary Central and Eastern Europe.

“The dispersal of the Slavs likely represents the final demographic event of continental magnitude that has permanently and fundamentally reshaped both the genetic and linguistic tapestry of Europe,” commented Dr. Johannes Krause, director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

The findings were disseminated on September 3 in the esteemed journal Nature.

_________

J. Gretzinger et al. Ancient DNA connects large-scale migration with the spread of Slavs. Nature, published online September 3, 2025; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09437-6

This article has been adapted from an original release provided by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.