The lingering consequences of a significant marine heatwave in the vicinity of Greenland during 2003 continue to exert influence on North Atlantic ocean ecosystems, even after several decades. Since that event, there has been a consistent and pronounced escalation in the frequency of marine heatwaves.

A comprehensive assessment, drawing upon over 100 scientific investigations, was undertaken by marine biologists from both Germany and Norway. Their findings indicate that marine heatwaves (MHWs) occurring in and subsequent to 2003 instigated “extensive and swift ecological transformations” across every stratum of oceanic life, encompassing everything from microscopic unicellular organisms to commercially vital fish populations and cetaceans.

Marine ecologist Karl Michael Werner, affiliated with the Thünen Institute of Sea Fisheries in Germany, and his collaborators have asserted that “The events of 2003, which followed a preceding warm year in 2002, heralded the onset of a protracted heating trend throughout numerous North Atlantic locales, a phenomenon unprecedented in prior observations.”

“Although the year 2003 represents the apex, with the highest incidence of MHWs recorded, several subsequent years exhibited similarly elevated numbers.”

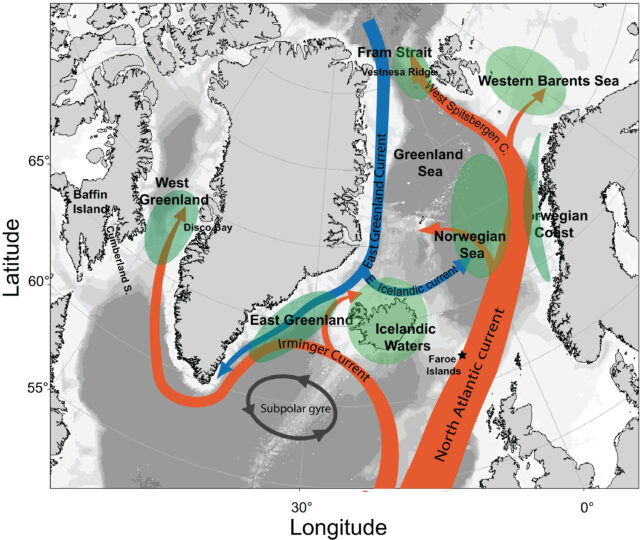

The North Atlantic was subjected to the 2003 marine heatwave due to a weakened subpolar gyre, which facilitated the ingress of substantial volumes of warm, subtropical water into the Norwegian Sea via the Atlantic Inflow. Concurrently, the usual flow of cooling Arctic waters into the Norwegian Sea was notably diminished.

These combined factors led to a dramatic reduction in sea ice coverage and a considerable surge in sea surface temperatures across the region. Within the Norwegian Sea, the elevated temperatures permeated to depths of up to 700 meters (2,300 feet).

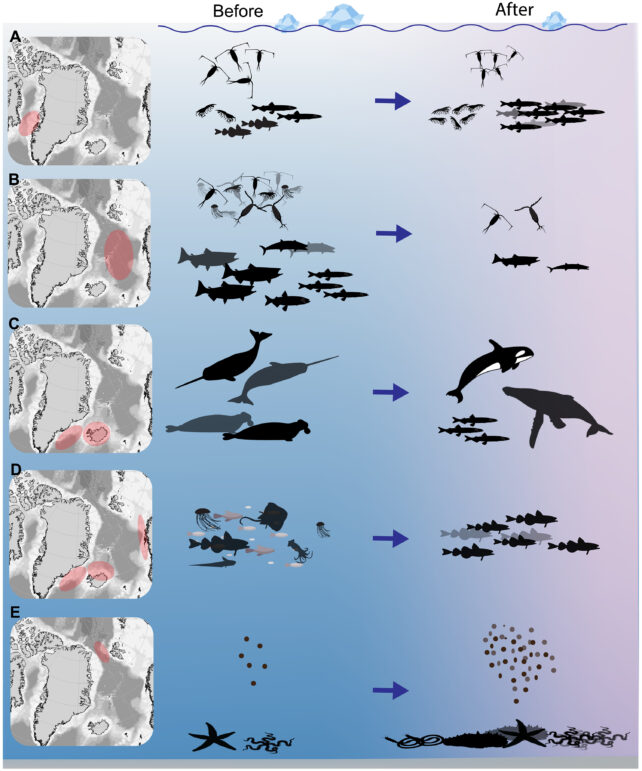

In line with typical responses to warming aquatic environments, species adapted to colder conditions experienced decline, while those that flourish in warmer climes expanded their presence into newly available ecological niches.

The researchers elucidate that “Every region examined demonstrated a shift from communities adapted to colder, ice-prone environments towards those favoring warmer waters, and the effects of this event reshaped socio-ecological dynamics.”

A precipitous decline in sea ice, observed in 2015, opened access to the waters for baleen whale species. Furthermore, orcas, which had been largely absent from these areas for over half a century, have been documented with increasing frequency since 2003.

Conversely, the authors report a substantial decrease. The authors report that catches of ice-dependent, cold-water-adapted narwhals (Monodon monoceros) and hooded seals (Cystophora cristata) located southeast of Greenland either markedly declined after 2004 or experienced a significant reduction in the mid-2000s.

Benthic organisms, such as brittle stars and polychaete worms, consumed the extensive phytoplankton blooms that ultimately settled on the ocean floor following the heatwave events. Atlantic cod, demonstrating opportunistic predatory behavior, is another species that appears to have benefited from the newly available food sources.

The 2003 heatwave coincided with the abrupt disappearance of sandeel (Ammodytes), a critical prey item for larger fish such as haddock. Subsequent ecological disruptions have mirrored the decline in capelin populations.

Capelin represent a crucial dietary component for Atlantic cod and whales inhabiting the North Atlantic. However, these fish have migrated northward in pursuit of cooler environments for feeding and spawning. Should global temperatures continue to rise, their options for southward migration become increasingly limited.

Such profound alterations can destabilize the ecological equilibrium, potentially posing long-term detrimental effects even to the most resilient marine life.

Werner and his colleagues observe that “The resultant ecological reorganization across these areas underscores the significant influence of extreme events on marine ecosystems.”

Werner further elaborates that “While one can forecast the impact of rising temperatures on organismal metabolism, a species may not derive advantages from such shifts if it becomes prey to predators after relocating northward or fails to locate suitable spawning grounds in its new environment.”

Marine heatwaves of this magnitude are not random occurrences; substantial evidence suggests their intensity, frequency, and spatial extent are intrinsically linked to anthropogenic activities, specifically the combustion of fossil fuels, which releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The majority of the surplus heat captured by these greenhouse gases is absorbed by the ocean.

Although the ramifications of human-induced climate change manifest differently across various regions, it is established that marine heatwaves are a prominent indicator of this phenomenon.

In the Arctic, marine heatwaves can exacerbate warming trends by leading to the melting of sea ice. This exposes darker ocean surfaces, which reflect less solar radiation and consequently absorb more heat.

This constitutes a concerning feedback loop, and despite the rapidly emerging consequences, the precise mechanisms driving marine heatwaves remain incompletely understood.

Werner and his team conclude that “The recurrent heatwaves following 2003 may have precipitated additional, as yet undetected, ecological implications that could potentially interact with other environmental stressors.”

“An understanding of the significance of the subpolar gyre and air-sea heat exchange will be vital for predicting MHWs and their cascading consequences.”