Palæontological investigations have been conducted on the 160-million-year-old fossilized remains of Anchiornis huxleyi, a species of non-avian theropod dinosaur dating back to the Late Jurassic period and unearthed from the Tiaojishan Formation in northeastern China. These exceptionally preserved specimens, complete with their feather integuments, have revealed that this particular dinosaur species had undergone a loss of aerial locomotion capabilities. This represents an exceptionally uncommon discovery, offering profound insights into the biology of organisms that inhabited the planet 160 million years ago and their influence on the evolutionary trajectory of flight in both avian ancestors and birds.

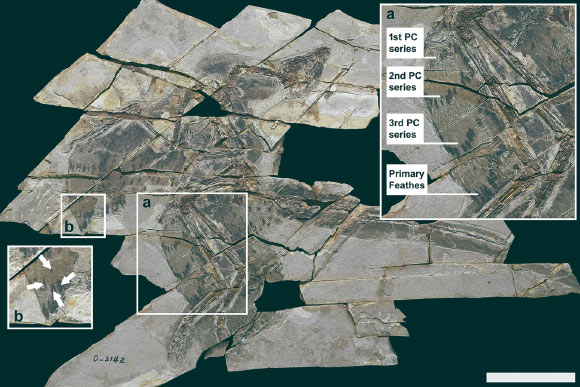

This fossil of Anchiornis huxleyi exhibits nearly complete wings and preservation of feather coloration, allowing for a detailed identification of wing morphology. Image credit: Kiat et al., doi: 10.1038/s42003-025-09019-2.

“This revelation carries substantial implications, suggesting that the development of flight throughout the evolutionary history of dinosaurs and birds was considerably more intricate than previously posited,” stated Dr. Yosef Kiat, a paleontologist at Tel Aviv University, and his research collaborators.

“Indeed, it is conceivable that certain species attained rudimentary flight capacities only to subsequently forfeit them during their evolutionary progression.”

“The dinosaurian clade diverged from other reptilian lineages approximately 240 million years ago.”

“Shortly thereafter, within an evolutionary context, numerous dinosaurs developed feathers—a distinctive, lightweight, and robust organic structure composed of protein, primarily utilized for aerial locomotion and thermoregulation.”

Around 175 million years ago, a distinct evolutionary branch of feathered dinosaurs, identified as Pennaraptora, came into existence. These represent the ancient progenitors of contemporary avian species and constitute the sole dinosaurian lineage that endured the cataclysmic mass extinction event marking the close of the Mesozoic Era 66 million years ago.

To our current understanding, the Pennaraptora group evolved feathers for the purpose of flight. However, it remains a possibility that shifts in environmental circumstances prompted some of these dinosaurs to lose their capacity for flight, analogous to extant species like ostriches and penguins.

Within the scope of this investigation, the researchers meticulously examined nine fossilized specimens belonging to a feathered pennaraptoran dinosaur species designated as Anchiornis huxleyi.

A remarkable paleontological find, these fossilized remains—along with several hundred similar discoveries—were preserved with their feathers intact, a testament to the unique geological conditions prevalent in the region during the fossilization process.

Specifically, the nine fossils subjected to analysis were selected due to their preservation of feather coloration, exhibiting a pattern of white plumage adorned with a black distal spot.

“Feathers undergo a growth phase lasting approximately two to three weeks,” explained Dr. Kiat.

“Upon attaining their full size, they detach from the nutrient-supplying blood vessels that sustained them during development, subsequently becoming inert structures.”

“Subjected to wear over time, they are shed and superseded by newly generated feathers—a process known as molting, which conveys significant evolutionary information: avian species reliant on flight, and consequently on the feathers that facilitate their aerial movement, undergo molting in an organized, progressive manner that preserves inter-wing symmetry, thereby enabling sustained flight during this physiological transition.”

“Conversely, in flightless avian species, the molting process tends to be more erratic and disorganized.”

“Consequently, an analysis of the molting pattern can provide definitive evidence regarding the flight capabilities of a particular winged organism.”

The preserved coloration of the integument in the fossilized dinosaurs originating from China afforded the scientific team the ability to discern the wing morphology, characterized by a continuous linear arrangement of black spots along the wing’s margin.

Furthermore, they were capable of differentiating between developing feathers that had not yet reached full maturity, as their nascent black spots exhibited deviations from the established black linear pattern.

A comprehensive examination of the developing feathers within the nine fossil specimens indicated that the molting did not adhere to a structured sequence.

“Drawing upon my extensive knowledge of extant avian species, I surmised a molting pattern strongly suggestive of flightlessness in these dinosaurs,” Dr. Kiat asserted.

“This constitutes an exceptionally infrequent and profoundly exciting discovery: the preserved pigmentation of the feathers granted us an unparalleled avenue to ascertain a functional attribute of these ancient organisms—transcending the purely structural information typically gleaned from skeletal and osseous fossil remains.”

“While feather molting might appear to be a minor anatomical detail, its examination in fossilized specimens has the potential to fundamentally alter our prevailing hypotheses concerning the origins of flight,” he elaborated.

“Anchiornis huxleyi has now been added to the roster of feathered dinosaurs that lacked the capacity for flight, underscoring the profound complexity and remarkable diversity inherent in the evolution of wings.”

The findings of this study have been formally published in the esteemed scientific journal Communications Biology.

_____

Y. Kiat et al. 2025. Wing morphology of Anchiornis huxleyi and the evolution of molt strategies in paravian dinosaurs. Commun Biol 8, 1633; doi: 10.1038/s42003-025-09019-2