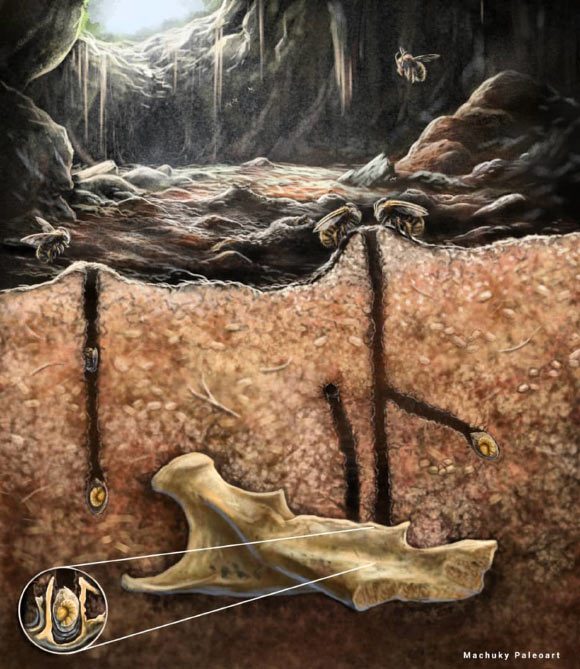

Bees exhibit a remarkable diversity in their species and behaviors, spanning from solitary varieties that excavate subterranean nests to gregarious species that construct intricate, compartmentalized dwellings. This spectrum of nesting strategies is partially evidenced in the paleontological record through trace fossils, with documented examples extending from the Cretaceous period through the Holocene epoch. In a recent publication, Lazaro Viñola López, a paleontologist at the Field Museum, and his collaborators have detailed an unprecedented nesting behavior, identified from trace fossils unearthed in a cave deposit on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola dating to the Late Quaternary. These isolated brood cells, designated Osnidum almontei, were discovered within cavities present in vertebrate skeletal remains.

Life reconstruction of the tracemaking bee nesting inside a cave and using bone cavities as containing chambers for some of the brooding cells. Image credit: Jorge Mario Macho.

“The initial ingress into the cavern is not excessively deep—we utilized a rope for rappelling,” stated Dr. Viñola López.

“During nocturnal exploration, one observes the glint of tarantula eyes. However, traversing approximately ten meters into the subterranean passage reveals the fossilized evidence.”

Multitudes of fossils were found interspersed with carbonate layers, indicative of past precipitation events.

A significant portion of these ancient remains belonged to rodents, though bones from sloths, birds, and reptiles were also present, representing over 50 distinct taxa. Collectively, these skeletal remnants narrated a compelling ecological narrative.

“Our hypothesis is that this cave served as a long-term dwelling for owls over numerous generations, potentially spanning millennia,” Dr. Viñola López elaborated.

“These avian predators would forage, then return to the cave to regurgitate indigestible matter.”

“We encounter the skeletal remains of their prey, avian fossils themselves, and even evidence of turtles and crocodiles that may have inadvertently entered the subterranean environment.”

Within the vacant alveoli of the mammalian mandibles, Dr. Viñola López and his colleagues observed that the sediment infill did not appear to be the result of random accumulation. Instead, it presented a smooth, almost concave surface.

“This morphology deviates from typical sedimentary infill patterns. Its recurrence across multiple specimens sparked my curiosity. It evoked associations with wasp constructions,” Dr. Viñola López remarked.

Some of the more widely recognized nests constructed by bees and wasps are those of social species, which coexist and rear their progeny collectively in extensive colonies—akin to the comb-like structures of paper wasps or the wax honeycombs of honey bees.

“Yet, the reality is that the majority of bee species are solitary. They deposit their eggs in small cavities, provisioning them with pollen for larval sustenance,” Dr. Viñola López explained.

“Certain bee species excavate galleries in woody material or soil, or repurpose existing empty apertures for nesting. Some taxa indigenous to Europe and Africa even fashion their abodes within discarded gastropod shells.”

To facilitate a more detailed examination of the suspected insect nests within the cave fossils, the researchers employed computed tomography (CT) scanning. This non-destructive technique involved X-raying the skeletal specimens from multiple angles, enabling the generation of three-dimensional reconstructions of the compacted material within the tooth sockets, thereby preserving the integrity of the fossils and the infill.

The morphology and architecture of the sediment formations bore a striking resemblance to the mud constructions produced by extant bee species. Intriguingly, some of these fossilized nests contained trace amounts of ancient pollen, meticulously sealed within by the maternal bees as a food source for their developing offspring.

The researchers posit that these bees employed a mixture of their saliva and soil to fabricate these minuscule individual brood chambers, each smaller than a standard pencil eraser.

The strategic utilization of bone cavities for nest construction may have offered a protective advantage, shielding the developing bee eggs from predation by other insects, such as wasps.

Due to the absence of preserved bee specimens, the research team was precluded from definitively identifying the species responsible for these unique nests.

Nonetheless, the distinct characteristics of these nests, differentiating them from previously documented bee constructions, permitted their taxonomic classification as fossil trace evidence.

These nests were formally designated Osnidum almontei, in homage to Juan Almonte Milan, the scientist credited with the initial discovery of the cave.

“Given the lack of associated bee exoskeletons, it is plausible that these nests were created by a species still extant today. Our understanding of the ecological habits of numerous bee species inhabiting these islands remains rudimentary,” Dr. Viñola López commented.

The scientific consensus suggests that this particular nesting behavior arose from a confluence of environmental factors. The scarcity of substantial soil cover on the region’s limestone substrate may have compelled these bees to seek out caves as alternative nesting sites, rather than resorting to terrestrial excavation as practiced by many related species.

Furthermore, the cave’s sustained role as a communal owl roost, resulting in the accumulation of significant quantities of regurgitated pellets over time, provided a readily available source of bone material, which the bees ingeniously exploited.

“This discovery underscores the remarkable adaptability and often unexpected behaviors of bees, capable of consistently surprising us. It also serves as a potent reminder of the critical importance of meticulous examination when interpreting fossil discoveries,” Dr. Viñola López emphasized.

The pertinent research paper has been published in the latest issue of Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences.

_____

Lázaro W. Viñola-López et al. 2025. Trace fossils within mammal remains reveal novel bee nesting behaviour. R Soc Open Sci 12 (12): 251748; doi: 10.1098/rsos.251748