While the woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), a creature well-adapted to frigid environments, ceased to exist approximately 14,000 years ago, the precise trajectory of its population decline remains largely enigmatic. A recent investigation spearheaded by researchers from the Centre for Palaeogenetics and Stockholm University has yielded a high-resolution genome derived from some of the most recent remnants of this extinct megafauna. These remains were discovered within the digestive tract of a wolf pup frozen in Siberia’s permafrost. When juxtaposed with two other Late Pleistocene woolly rhinoceros genomes, the findings indicate a consistent population size without any discernible genetic markers of a precipitous decline in the period immediately preceding the species’ demise. This stands in contrast to other vanished species and extant endangered populations, which exhibit clear genomic evidence of recent population attrition.

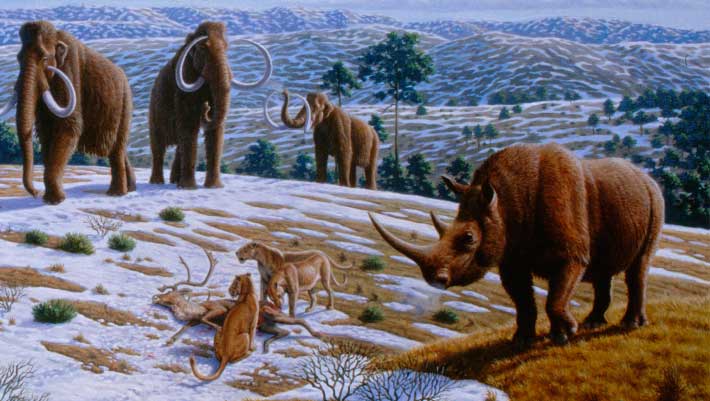

This image depicts a Pleistocene landscape in northern Spain with woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius), equids, a woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), and European cave lions (Panthera leo spelaea) with a reindeer carcass. Image credit: Mauricio Antón.

The woolly rhinoceros, a herbivore adept at surviving cold climates, initially emerged around 350,000 years ago. It was once prevalent across northern Eurasia before its eventual extinction, which occurred roughly 14,000 years ago.

Commencing approximately 35,000 years ago, its geographical distribution began to contract progressively eastward, a shift most likely instigated by adverse environmental conditions prevalent in western Europe.

The species managed to endure in northeastern Siberia, exhibiting dynamic alterations in its habitat in response to climatic shifts, until its eventual disappearance from the fossil record.

Prior genetic analyses had not identified indications of recent inbreeding in specimens dated to 18,400 and 48,500 years ago. However, up to this point, no complete genome had been successfully extracted from a sample dating so closely to the species’ extinction.

“The ability to recover genomes from individuals that inhabited the planet just before extinction presents significant challenges, yet it can furnish crucial insights into the factors precipitating a species’ disappearance, which may also hold relevance for contemporary endangered species conservation efforts,” remarked Dr. Camilo Chacón-Duque, the study’s corresponding author.

The newly sequenced woolly rhinoceros genome was derived from muscular tissue discovered within the digestive tract of a permafrost-preserved wolf pup unearthed in northeastern Siberia.

Radiocarbon dating confirms that both the wolf and the tissue are approximately 14,400 years old, classifying this specimen among the most recently identified woolly rhinoceros remains.

“The endeavor to sequence the full genome of an Ice Age creature found encapsulated within another animal’s stomach has never been undertaken before,” Dr. Chacón-Duque stated.

Through a comparative analysis of this novel genome with two previously published Late Pleistocene woolly rhinoceros genomes, the research team meticulously investigated genetic diversity across the genome, patterns of inbreeding, genetic load, and fluctuations in population size in the period proximate to the species’ extinction.

The findings revealed an paucity of extended homozygous segments, a characteristic typically indicative of recent inbreeding. This observation led the researchers to infer a stable population size merely a few centuries prior to the species’ demise.

“The process of extracting a complete genome from such an unconventional sample was both exhilarating and remarkably demanding,” shared Sólveig Guðjónsdóttir, the study’s lead author.

Furthermore, the researchers meticulously reconstructed the effective population size dynamics over time, identifying no discernible reduction at the advent of the Bølling-Allerød interstadial, a warmer climatic phase that commenced approximately 14,700 years ago.

Their conclusions suggest that the extinction of the woolly rhinoceros likely occurred with rapidity, possibly during the climatic transitions of this period, or across a timescale too abbreviated to leave an detectable genomic trace.

“Our analyses indicated a surprisingly consistent genetic profile, with no discernible alterations in inbreeding levels over tens of thousands of years preceding the woolly rhinos’ extinction,” commented Dr. Edana Lord, a co-author of the investigation.

“The data we’ve gathered demonstrates that woolly rhinos maintained a viable population for 15,000 years subsequent to the initial human ingress into northeastern Siberia, leading us to posit that climate warming, rather than anthropogenic hunting, was the primary driver of their extinction,” added Professor Love Dalén, another co-author.

The research findings have been published in the scientific journal Genome Biology and Evolution.

_____

Sólveig M. Guðjónsdóttir et al. 2026. Genome Shows No Recent Inbreeding in Near-Extinction Woolly Rhinoceros Sample Found in Ancient Wolf’s Stomach. Genome Biology and Evolution 18 (1): evaf239; doi: 10.1093/gbe/evaf239