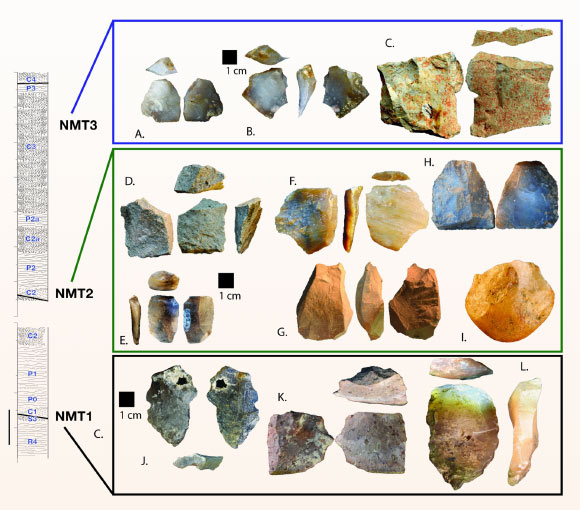

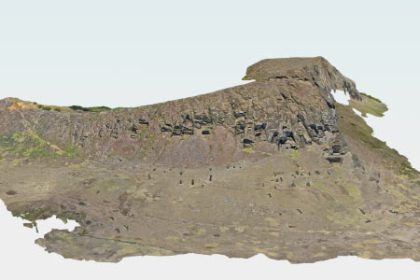

Significant archaeological excavations at the Namorotukunan site, situated within Kenya’s Koobi Fora Formation in the northeastern Turkana Basin, have yielded Oldowan stone implements from three distinct strata. These findings, representing a temporal span of approximately 300,000 years (from 2.75 to 2.44 million years ago), strongly suggest a sustained tradition of lithic craftsmanship, underscored by evidence of deliberate raw material selection.

Research into the nascent stages of tool production, with origins exceeding 3 million years ago, emphasizes percussion techniques. This method of fabrication is prevalent throughout the hominin fossil record and is also observed among other primate species.

The utilization of tools, frequently associated with foraging for readily accessible resources, represents a recurrent behavioral characteristic observed in certain contemporary primate populations.

The earliest documented instances of systematic manufacture of sharp-edged stone artifacts, characteristic of the Oldowan industry, are unearthed at eastern African locales within the hominin evolutionary narrative. These include Ledi-Geraru and Gona in Ethiopia’s Afar Basin (dated to 2.6 million years ago) and Nyayanga in western Kenya (dating between 2.6 and 2.9 million years ago).

Professor David R. Braun, an anthropologist affiliated with the George Washington University and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, along with his research team, unearthed numerous collections of lithic artifacts from three distinct stratigraphic levels. These layers have been chronometrically dated to 2.75, 2.58, and 2.44 million years before the present at the Namorotukunan site.

“This locale offers a remarkable narrative of unbroken cultural development,” stated Professor Braun.

“What is evident here is not an isolated inventive spark, but rather an enduring technological lineage.”

“Our findings lead us to infer that the deployment of tools might have constituted a more widespread adaptive strategy among our primate forebears,” commented Dr. Susana Carvalho, who holds the position of Scientific Director at Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique.

“Namorotukunan provides an infrequent perspective on a vastly altered ancient environment, characterized by shifting river systems, prevalent wildfires, and encroaching arid conditions, yet the tools remained consistently present.”

“For a duration of 300,000 years, the same artisanal practices persisted, potentially illuminating the genesis of one of our most ingrained behaviors: leveraging technology to achieve stability amidst environmental flux,” remarked Dr. Dan V. Palcu Rolier, a researcher associated with GeoEcoMar, Utrecht University, and the University of São Paulo.

“Early hominins demonstrated exceptional proficiency in the creation of sharp-edged stone implements, displaying a sophisticated level of skill and accumulated knowledge passed down through innumerable generations.”

Through a comprehensive analysis employing techniques such as volcanic ash dating, the interpretation of magnetic signatures preserved in ancient sediments, geochemical profiling of lithic materials, and the examination of microscopic botanical remnants, the research team meticulously reconstructed a profound climatic narrative. This historical context is crucial for comprehending the pivotal role of technology in the trajectory of human evolution.

The hominins responsible for crafting these tools navigated periods of dramatic environmental instability. Their adaptable technological capabilities facilitated access to novel dietary sources, including animal flesh, thereby transforming challenging circumstances into a survival advantage.

“These discoveries indicate that by approximately 2.75 million years ago, hominins had already achieved proficiency in manufacturing sharp stone tools, suggesting that the inception of Oldowan technology predates our prior estimations,” stated Dr. Niguss Baraki, a researcher at the George Washington University.

“At Namorotukunan, the presence of cut marks on faunal remains directly links stone tools to meat consumption, revealing an expanded and sustained dietary repertoire that persisted through evolving landscapes,” added Dr. Frances Forrest, a researcher at Fairfield University.

“The paleobotanical evidence paints a vivid picture of ecological transformation: the landscape transitioned from verdant wetlands to arid, fire-affected grasslands and semi-desert environments,” observed Dr. Rahab N. Kinyanjui, a researcher affiliated with both the National Museums of Kenya and the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology.

“Despite these shifts in vegetation, the tool-making processes remained remarkably consistent, a testament to their resilience.”

The published findings are featured in the current issue of the journal Nature Communications.

_____

D.R. Braun et al. 2025. Early Oldowan technology thrived during Pliocene environmental change in the Turkana Basin, Kenya. Nat Commun 16, 9401; doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-64244-x