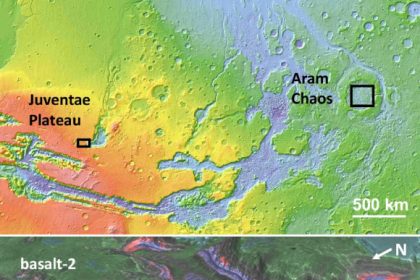

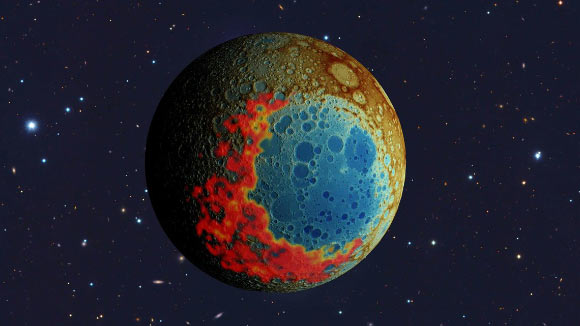

Approximately 4.3 billion years ago, during the nascent stages of our Solar System, a colossal celestial body collided with the far hemisphere of the Moon, engendering a colossal impact scar known as the South Pole-Aitken basin. This impact feature represents the most extensive crater on the lunar surface, extending over 1,200 miles from pole to pole and 1,000 miles from flank to flank. The basin’s elongated configuration is attributed to a tangential impact event rather than a direct, head-on collision. Contrary to the prevailing hypothesis that the basin originated from an impactor approaching from a southerly trajectory, recent investigations suggest that the basin’s shape, narrowing towards the south, indicates an impact originating from the north.

The South Pole-Aitken impact basin on the far side of the Moon formed in a southward impact. Image credit: Jeff Andrews-Hanna / University of Arizona / NASA / NAOJ.

“The distal extremity of the basin ought to be cloaked in a substantial stratum of material dislodged from the Moon’s interior by the impact, whereas the proximal end should be devoid of such deposition,” remarked Dr. Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna, a planetary scientist affiliated with the University of Arizona.

“This implies that the planned Artemis missions will alight upon the down-range rim of the basin—the optimal locale for scrutinizing the most expansive and ancient impact structure on the Moon, where the bulk of the ejected debris, originating from profound depths within the lunar mantle, is likely to be concentrated.”

It has long been posited that the early Moon was subjected to significant melting due to the thermal energy released during its formation, resulting in the creation of a global magma ocean.

As this magma ocean underwent crystallization, denser minerals precipitated and settled to form the lunar mantle, while lighter constituents ascended to constitute the lunar crust.

However, certain elemental components were precluded from incorporation into the solid mantle and crust, consequently accumulating within the residual liquid phases of the magma ocean.

These ‘residual’ elements encompassed potassium, rare earth elements, and phosphorus, collectively designated as KREEP.

According to Dr. Andrews-Hanna and his research consortium, these elements have been observed to exhibit a particularly high abundance on the Moon’s near side.

“Consider the instance of placing a can of soda in a freezer; you might observe that as the water solidifies, the high-fructose corn syrup, due to its lower freezing point, resists solidification until the final moments, becoming highly concentrated in the last vestiges of liquid,” explained Dr. Andrews-Hanna.

“We hypothesize that a comparable phenomenon transpired on the Moon with KREEP.”

“As it cooled over an extended geological epoch of millions of years, the magma ocean progressively solidified, differentiating into crust and mantle.”

“Ultimately, a state was reached where only a minuscule volume of liquid remained, sandwiched between the mantle and the crust, constituting this KREEP-rich material.”

“All the KREEP-rich material and radiogenic heat-producing elements were somehow sequestered on the Moon’s near side, inducing thermal elevation and consequently triggering intense volcanic activity that sculpted the dark basaltic plains, which constitute the familiar visage of the Moon’s face as viewed from Earth.”

“Nevertheless, the underlying reasons for the aggregation of KREEP-rich material on the nearside, and its subsequent evolution over time, have remained an enigma.”

“The lunar crust exhibits a considerably greater thickness on its far side compared to its near side, which perpetually faces Earth—an asymmetry that continues to perplex scientists to this day.”

“This asymmetry has profoundly influenced every facet of the Moon’s developmental history, including the terminal phases of the magma ocean’s existence.”

“Our theoretical framework proposes that as the crust augmented in thickness on the far side, the underlying magma ocean was laterally displaced, analogous to toothpaste being extruded from a tube, until the majority of it accumulated on the near side.”

The recent investigation of the South Pole-Aitken basin has unveiled a notable and unexpected asymmetry surrounding the crater, which strongly corroborates this very hypothesis: the ejecta blanket situated on its western periphery is replete with radioactive thorium, a characteristic notably absent from its eastern flank.

This observation suggests that the scar left by the impact served as a conduit, exposing the Moon’s superficial layer and providing access to the boundary differentiating the crust overlaid by the final remnants of the KREEP-enriched magma ocean from the ‘ordinary’ crust.

“Our research demonstrates that the distribution and elemental composition of these materials align precisely with the projections derived from our modeling of the magma ocean’s later evolutionary stages,” stated Dr. Andrews-Hanna.

“The final vestiges of the lunar magma ocean congregated on the near side, where we observe the most significant concentrations of radioactive elements.”

“However, at an earlier epoch, a thinly distributed and discontinuous layer of the magma ocean would have existed beneath portions of the far side, thus accounting for the presence of radioactive ejecta on one aspect of the South Pole-Aitken basin.”

The study has been published in the esteemed journal Nature.

_____

J.C. Andrews-Hanna et al. 2025. Southward impact excavated magma ocean at the lunar South Pole-Aitken basin. Nature 646, 297-302; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09582-y